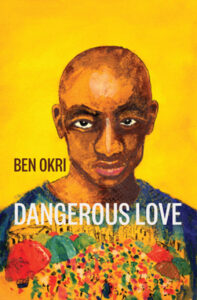

[Other Press; 2022]

Many of the great epics are driven by a tried and true formula, one which puts a little story in the foreground of a much larger one involving war. Thus Odysseus makes his way back to Penelope in the aftermath of the Trojan War, and Dante pursues Beatrice through an afterlife packed with saints and demons.

So, too, with Ben Okri’s Dangerous Love. Yes, the Nigerian Civil War is over or as over as it can be. You may have noticed that we’re still fighting ours in the United States, so why should it be different for those who lived through the 1967–70 conflict between Nigeria and the secessionist Republic of Biafra? Okri’s characters “were all children when the war happened,” says the author in an introduction. Perhaps that explains the mildly anesthetic tone throughout a book in which tension is always there just under the surface and minding one’s own business is a way of life; it is as though the iconic New York City subway slogan has been rewritten to say, “If you see something, say nothing.”

Meanwhile, Omovo has fallen madly in love with Ifeyiwa, and she feels the same. We meet the two sweethearts in the early days of their infatuation, when passion is at its headiest. Ifi, as she is called, sends Omovo a note saying she wants to see him badly and sets up a rendezvous for the next day. There’s only one catch, which is that Ifi is married to Takpo, who is not very nice in the first place, and let’s just say that his disposition doesn’t improve as he grows more suspicious of the young lovers.

Omovo works for a shipping company, though he isn’t exactly employee of the month material. He is habitually late, and when he tries to explain one day why he has shown up three hours after everyone else, his supervisor says, “Shut up! Listen, young man, you are the most frivolous, unserious, uncommitted, unconscientious, and insubordinate member of this department.” Omovo’s real job is mooning over Ifi, and when he’s not doing that, he devotes himself to painting (or “arting,” as a friend calls it). Like most artists, he has backed into serious creativity; what was once a childhood hobby becomes a passion as well as a way “to come to terms with the miasmic landscapes about him.”

And are those landscapes ever miasmic! Omovo has studied the great artists of Europe, and his masters include Diego Velázquez “and his fastidious quest for truth,” as well as Leonardo da Vinci, whom he quotes as saying, “’Perfection is made up of details, but detail is not perfection.’” He is especially taken with Michelangelo’s statue of the David who is stepping out of obscurity and transforming himself from shepherd boy to the savior of his people. But his ultimate hero is Pieter Brueghel, whom he calls “the wild man of the imagination,” who depicts a “quivering world of nightmares.”

That phrase describes aptly the world of postwar Nigeria. And it describes much of what Omovo paints as well; a key work here is his unsettling depiction of “a snot-colored scumpool full of portentous shapes and heads with glittering eyes.” Historically, political strongmen and their minions have not been fans of abstract art, and when the painting is shown at a gallery, a soldier denounces it as “mocking national progress” and “corrupting national integrity.” Omovo is interrogated and denounced as a reactionary, and his painting is confiscated, to all of which he reacts with a surprising indifference. Indeed, Omovo seems in many ways detached from the day to day, his focus directed for the most part to just two things: whatever he’s going to paint next and his closeted love for Ifi.

That might be the best way to handle yourself in a world where baffling violence is as much a part of life as a breeze or birdsong. One night he and his friend Keme stumble across the body of a dead girl. Afraid they will become suspects if they go directly to the authorities, Keme reports their discovery anonymously, but the only upshot is a brief article in the newspaper saying the girl probably died in a ritual killing and that such murders are almost impossible to investigate.

That dead girl appears again in the book’s finale, and Omovo makes her into a kind of macabre Mona Lisa in what he calls “my first real painting,” one that dramatizes the tensions of postwar culture without resolving them. Meanwhile, his biggest concern is his secret life with Ifi—his real time, one might say, as opposed to the parching and dusty tedium of ordinary days. If these two bond over love, they bond over books as well. And just as Western painting has shaped Omovo’s art, so, too, are the lovers’ conversations peppered with references not only to Nigerian authors, but also to Walt Whitman and “a Russian writer called [Anton] Chekhov.” (Later, Omovo and a friend talk about their fondness for the English thriller writer Hadley Chase.)

Is the Western canon at work just under the surface here, or is it simply a matter of two seemingly different cultures having a common base? When the camera pulls back, certainly there is a Balzacian detachment, a nonjudgmental noting of a community’s manners and mores, of people keeping their heads down and finding meaning and purpose where they can. Ifi reaches a crisis point and seems to think that, while Omovo’s pure love is greatly to be preferred over Takpo’s toxic brand, she may not want to submit to any man’s dominance. One thinks of how, in Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady, Isabel Archer is drawn to kind Caspar Goodwood as opposed to cruel Gilbert Osmond but ends up rejecting both.

This is not at all to say that Dangerous Love takes on extra value because it can be discussed easily in terms of its Western counterparts. In the face of the movement for greater diversity in academe, Saul Bellow denigrated the achievement of other cultures and then sharpened his pushback by asking rhetorically, “Who is the [Leo] Tolstoy of the Zulus?” By way of reply, Ta-Nehisi Coates quotes the writer Ralph Wiley as saying, “Tolstoy is the Tolstoy of the Zulus,” a phrasing which should remind us that literature is its own ecosystem, one that refracts rather than reflects the world from which it springs. That world consists of an infinite number of microcosms, but each has most-favored nation status, and in a time like ours, when the flow of information is instantaneous and free, each shapes the macrocosm that contains them all.

In the arts, there are no borders—Chekhov can fly to Nigeria as easily as Ben Okri can pop up anywhere in the world. The philosopher Martha Nussbaum says that each person’s life is a “complex narrative of human effort in a world full of obstacles.” Isn’t that true of Omovo? Isn’t it true of you?

David Kirby teaches at Florida State University. His latest books are Help Me, Information, a poetry collection, and a textbook modestly entitled The Knowledge: Where Poems Come From and How to Write Them.

This post may contain affiliate links.