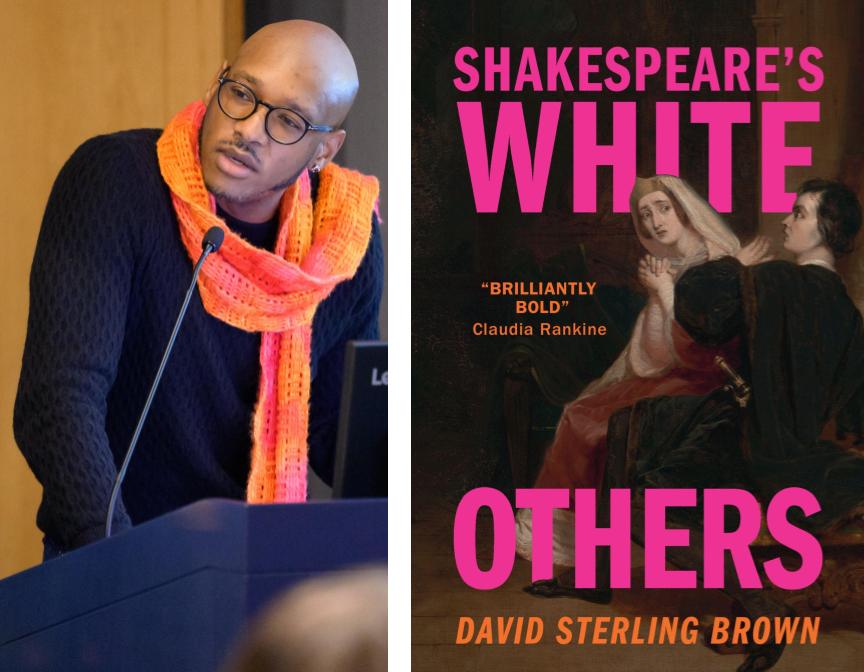

Dr. David Sterling Brown, Associate Professor of Shakespeare and critical race studies at Trinity College (CT), first collaborated with The Racial Imaginary Institute (TRII) in 2021 as a Mellon/ACLS Scholar. He eventually joined our curation team and has since made invaluable contributions to TRII. David has over the last years contributed articles to the website on contemporary manifestations of racialized discourse and has been an active conversant in our discussions as we move toward our next symposium, “On the Human.” The evident rigor and breadth of knowledge in Shakespeare’s White Others made me enthusiastic to engage with David further about his work. The following is the beginning of a conversation I hope will continue in the years to come.

Claudia Rankine: Let’s begin with the title, Shakespeare’s White Others. Your use of the dynamic of othering in the title at first seems like a reversal of how we traditionally think about othering as the first result of white violence and privilege. Here it becomes the ultimate outcome rather than the byproduct, which in your brilliant reading lands back onto whiteness itself. The white other in your reading lives between blackness and whiteness while presenting as white. Could you speak to how you followed the act of othering home?

David Sterling Brown: Absolutely, Claudia—thank you for that important question. “Follow[ing] the act of othering home” is such an apt phrase because home is where the heart of the problem lies. Prior to drafting this book, I wrote something else that I thought would be my first book. I titled it Black Domestic Matters (BDM). That study considered how much Black lives mattered in the early modern English domestic sphere. I wanted to argue that articulations of anti-Black anxieties intensify progressively in Shakespeare’s major plays that feature his four most visible and vocal Black characters (Aaron, Othello, Cleopatra and, I argue, Caliban). But then I realized, thanks to the help of my mentor-collaborators Dr. Melissa Shields Jenkins and Dr. Arthur L. Little, Jr. that I hadn’t pushed my thinking in BDM far enough, especially with respect to the impact I wanted the work to have on Shakespeare Studies and beyond. In hindsight, I see I was not complicating the issue enough because of course anti-Blackness would exist in Shakespeare’s plays featuring Black characters. Nevertheless, the worthwhile process of drafting BDM, in addition to my teaching experiences, showed me how anti-Blackness persisted in Shakespeare’s plays even in the absence of somatically Black people. The question I then needed to answer was “How?”

I recall an “aha!” moment when I was teaching my Shakespeare course at the University of Arizona years ago: My students and I paused on a scene in Much Ado About Nothing where the character Hero, accused of being unfaithful to her fiancé, Claudio, “fall[s] into a pit of ink,” as her father, Leonato, charges. When we slowed down on this moment and thought about the visual that Shakespeare constructed, we acknowledged the play’s invocation of an invisible Black woman, one of two instances in the play. It was then that I became captivated by the way Shakespeare’s white-centric plays contain anti-Blackness, and sometimes so subtly that readers, theatergoers, stage practitioners, students, and educators gloss over such moments that construct whiteness within a dichotomy that excludes real Black people yet imagines us in some way. I became curious about the anti-Black work that was happening and set out to determine the lines along which such divisions were occurring within whiteness, divisions that have real-world implications for real Black people. I must note that an early 2019 conversation with my former NYU advisor Dr. John Michael Archer lit a fire under me: I told him I wanted to other whiteness. He said, “If anyone can do it, you can.” Such lasting words of encouragement; I shall never forget them.

To follow the act of othering home is to go to the source of the problem, that being white people who themselves regularly enforce differences between ideal and less-than-ideal whiteness, as sociologist Matthew Hughey argues in his scholarship. I highlight the white problem in Shakespeare’s White Others through a guiding inquiry in my introduction. I ask, “How does it feel to be a white problem?,” a question that builds on W. E. B. Du Bois’s “How does it feel to be a problem?” query posed in The Souls of Black Folk. Coloring his question with “white” opens the door for a difficult, necessary conversation about how whiteness is a problem and how whiteness itself can be, and is, othered in ways that resonate with how Black people are othered. This is what makes the process of othering whiteness crucial to understand. The issue with anti-Blackness starts at home.

The white other in your reading lives between Blackness and whiteness while presenting as white. Their positionality allows whiteness to shine even brighter so that Shakespeare’s use of othering confirms white supremacy and is not subversive. In fact, you define the white other as a “powerful mechanism” enabling white dominance. But might we say that by having this dynamic pointed out by you, the scholar, that is how the subversive reversal comes into play and is activated?

I appreciate your formulation, Claudia, the idea that the white other lives in between Blackness and whiteness. “Lives” is the operative word for me because so long as the white other buffer between Black and white survives (survival that is essential for maintaining white dominance), it will remain incredibly difficult for anti-racist efforts to concentrate on Black people, on the bottom of the racial hierarchy, because anti-Blackness gets generated with or without Black folks in the mix. See the dilemma? Shakespeare, whom I position in the book as a theorist of whiteness, calls attention to the powerful mechanism that is the white other figure found in his work and outside of it. Thus, Shakespeare’s plays—especially the traditional race plays, i.e., Titus Andronicus, Othello, Merchant of Venice, The Tempest, and Antony and Cleopatra—contain subversive moments that shift the optic for viewers and readers.

Yet, the plays, especially his white-centric texts like Hamlet, The Comedy of Errors, Richard III, and Romeo and Juliet, which I touch on in the book, stop at being wholly subversive by concluding with valorizations of ideal whiteness. I assert in Shakespeare’s White Others that “the white self paradoxically needs but cannot stand the ontologically insecure version of itself, which it must constantly acknowledge only to dismiss, discourage, disappoint, disparage and attempt to destroy.” As seen in all the plays I examine in Shakespeare’s White Others, there is a purging of the white other who does not conform to the dominant culture’s norms. That is the ultimate act of restoration in Shakespeare’s plays. Recognizing the ultimate act of subversion does, indeed, depend on the viewer or reader acknowledging my scholarly intervention and the dynamic I bring to light for my audience. Moreover, my virtual-reality art gallery that complements my book helps people see the dynamic through visual art based on Shakespeare’s plays, art I found through the Folger Shakespeare Library Digital Image Collection.

I am fascinated by your argument that colorblind casting is less effective in Shakespeare given that the white others are marked on/in their white bodies by blackness. The recognition of blackness is crucial in the drama of their othering. It is in contrast to their whiteness that the black mark sullies, weakens and criminalizes them. Are you saying a Black actor erases the layers of contrast?

The short answer to your question is “no.” Now, for the long answer: In the book I argue, “With respect to anti-Blackness, othering whiteness also exposes what is wrong with promoting notions of colorblindness.” In part, I’m drawing on Philip A. Mazzocco’s The Psychology of Racial Colorblindness, a study that argues for the importance of seeing color, of not ignoring the real psychological implications of what it means to be Black or white or, dare I say, white other. I add that, “othering whiteness complements discourse suggesting that colorblindness is harmful in social, cultural, political, pedagogical and theatrical practice.” Like many scholars within and outside of my field, I eschew the ableist term “colorblind” in favor of “color-conscious.” Your query reminds me of how I had to think through what the white other’s presence means for the Black actor who gets cast in that role.

In 2021, I was finalizing Shakespeare’s White Others when The Tragedy of Macbeth—directed by Joel Coen and starring Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand—debuted. I was both nervous and excited because of the film’s potential implications for my book’s intraracial color-line and white other theories. I wish the Black actor erased the layers of contrast but, in fact, the opposite happens. In the middle of Macbeth, Malcolm (son of the Scottish King whom Macbeth kills) refers to the titular character as “black Macbeth.” This is a prime example of how color-conscious casting enhances the intended effects of the white other’s presence in a text. By the time we arrive at the play’s “black Macbeth” moment, Macbeth becomes a sinful murderer who violates hospitality code. He proves himself as a less-than-ideal white man, or white other. Washington’s physical Blackness works for an agenda that equates Black with bad. He plays a villain and his Blackness is covertly villainized all while he assumes a starring role in a film adaptation that, on the surface, seems harmless in the anti-Black context . . . but it is not.

That a Black actor’s skin color could be covertly, or unwittingly, commodified in this way is nothing new. In the nineteenth century and beyond, as scholar Lisa M. Anderson observes in her generative essay titled “When Race Matters: Reading Race in Richard III and Macbeth” in Colorblind Shakespeare, Black actors such as Ira Aldridge could assume starring roles like Richard III, a figure who is comparable to Macbeth in terms of villainy, in part because their Blackness amplified the notion that said character is bad, violent, sinful, out of control. Anderson explains, “A black Richard adds another level of signification that cannot help but recall representations of black men throughout the history of American theatre and film.” A somatically Black white other does similar work, perhaps even more so.

I am a humble admirer of your work in part because it clearly addresses a dynamic that we as a society have had a difficult time grasping—white dominance is at play in the most segregated of places. These places ironically are where whiteness is policed and enforced most insistently. The justification of a worldview dependent on anti-Blackness means that the benevolent construction of whiteness needs to be enforced as much as those perceptions created around the demonization of Blackness. Often we are policed by the statement that we can’t place contemporary thinking on the work in the past as if those canonical works weren’t responsible for today’s thinking. It’s the insistence of beliefs perpetuated by works in the canon that normalize violence and anti-Blackness. You write in the introduction to the book that “Shakespeare strategically othered white figures in his dramatic oeuvre to condition dominant English attitudes . . .,” in service of white identity formation. I am interested in your ability to frame this as an “overt investment” and action.

First, it’s an honor to learn that you, Claudia—someone whose work and work ethic I have great admiration and respect for—admire my work. That means a lot for the intellectual legacy I hope to leave behind, thank you! Regarding your inquiry, I think about it this way in terms of the overt investment: As an artist, as a playwright, Shakespeare certainly operated with a distinctly high level of ambition and at a rate that outpaced his playwright peers. Maybe they had no desire to match his output, but that is beside the point. What I want to illuminate is how his productivity helps address your thoughts regarding the benevolent construction of whiteness and the demonization of Blackness.

Let’s imagine Shakespeare’s white, contemporary rival Christopher Marlowe, a brilliant playwright who wrote plays such as The Jew of Malta and Doctor Faustus, was conscientiously writing and staging undeniably pro-Black anti-racist plays because he saw the pervasiveness of early modern English anti-Black racism. You know, I’m having fun with this hypothetical scenario, so let’s go even further into the realm of pro-Black anti-racist fantasy: Let’s add that Marlowe’s desire to abolish anti-Black racism, and educate his contemporaries, came from his ability to look into the future and see what Summer 2020 would look like in the United States, and globally, if he did not actively work toward making change on behalf of Black people (whom it took British historians a very long time to admit even existed in England, as English historian Peter Fryer posits). During his career, Marlowe produced only a fraction of the plays Shakespeare did. So, even if his hypothetical pro-Black, anti-racist work was well received, the impact would not be as great as a playwright who is producing more work, a playwright we might read as a synecdochic representation of the white supremacist machine that must work around the clock to stabilize its unstable hierarchical position. For things to change, pro-black, antiracist efforts must outpace racist ones, as I explain in a Los Angeles Review of Books essay. And just to be clear, I do believe Shakespeare tried to challenge his contemporary audience.

Your chapter on Hamlet and the Fall of White Masculinity brought me back to the production of Hamlet at St. Ann’s Warehouse here in New York. Hamlet was played by the brilliant actress Ruth Negga. The thought that it is a play about white people watching other white people made me smile in its accuracy. I wonder if you saw that production and how you read a woman and a Black person in that role?

You know, sadly, I did not see that production. However, thanks to Simon Godwin’s Shakespeare Theatre Live! series, I got the opportunity in 2021 to be in conversation with Ruth Negga and director Yaël Farber about that Hamlet production, and the gender/race dynamic came up during our chat. That my observation about Hamlet centering white people watching other white people made you smile in its accuracy is a comment I deeply appreciate. It reminds me of something my Shakespeare colleague Dr. Joe Stephenson said to me about my book when I gave a lecture to his grad students recently: that some of my book’s most compelling and necessary observations come from concisely articulated statements that highlight what is actually obvious in the plays. It’s all “hidden in plain sight,” to borrow one of my Introduction’s subheadings.

For me, those obvious moments became points of entry for broader analyses facilitated by my “intraracial color-line” and “white other” concepts, the former of which builds on sociologist W. E. B. DuBois’s interracial color-line theory outlined in The Souls of Black Folk and on sound studies scholar Dr. Jennifer Lynn Stoever’s “sonic color line” theory outlined in The Sonic Color Line: Race and the Cultural Politics of Listening. In the “white other” context, seemingly complicating a performance by having a traditionally white male character, a white other at that, played by a Black woman reinforces the white other’s function on the page and on the world’s stage. Such casting choices then capitalize on the actor’s somatic Blackness and their emblematic blackness, with the latter reflected through color-coded negative stereotypes that get attributed to women, for example, in the case of Negga as Hamlet. In my book, I write about Hamlet’s unmanliness. I imagine having a woman play Hamlet would illuminate that aspect of his character in ways that help reveal his white otherness.

Your book could have been called The Other White Tragedy. You extend the list of Shakespeare’s race plays in your book, but given your definition of the white other, couldn’t the entire Shakespearean oeuvre be considered? Is there a volume two on the way?

Indeed, it could have been called that, Claudia. But that’s just one too many words for a book title, don’t you think? I mean, if I do the math with just two of your books—Citizen and Just Us—I see you’ve done with only three words and two books what I did with three words and one book! On a serious note, I’m delighted you picked up on my desire to expand that conversation around whiteness in the canon. In the book, I center tragedy partly because it is the genre I gravitate toward. I appreciate the problems that arise in such texts and how we are confronted with those problems from the very start; and I appreciate how the violence is infused with meaning. So, the short answer to your question is “yes.” The entirety of Shakespeare’s oeuvre, dramatic and non-dramatic literature, could and should be considered with respect to the white other. It is my hope that Shakespeare’s White Others will be a springboard for new analyses about the plays and poetry I did not touch on or even the plays I briefly address such as Much Ado About Nothing and The Comedy of Errors.

In 2022, I served as senior editor of Shakespeare Studies’ 50th anniversary volume that centered on racial whiteness. That volume gestured toward the work I had coming in my book and it built on critical whiteness studies scholarship and past early modern critical race studies work. The essays in that volume derived from a two-part Shakespeare Association of America seminar I organized and led in 2020, with Drs. Patricia Akhimie and Arthur L. Little, Jr. as two of my seminar’s four respondents. In that journal issue, there’s more exploration of Shakespeare’s canon that goes where I don’t go in my book but not specifically in conjunction with the “white other” and “intraracial color-line” concepts; therefore, there is still so much more work to do even as the journal contributors helped move forward the conversation around Shakespeare and whiteness.

In a way, there is an unofficial volume two on the way through Hood Pedagogy, my next book which is under contract with Cambridge University Press. In Fall ’23, shortly before your powerful “Framing Black Female Subjectivity” Trinity College Bicentennial Symposium keynote and our live conversation that followed, I recorded a podcast episode with Dr. Thomas Dabbs for his fabulous “Speaking of Shakespeare” series. There, I said a bit more about Hood Pedagogy, which is also a phrase I deploy in the last pages of Shakespeare’s White Others as I lead into the book’s concluding words. My second book will, indeed, be an opportunity for me to build on Shakespeare’s White Others and advance its critical agenda.

At the close of this brilliantly bold book I appreciate the addition of your own story of harassment by local police. Your precarity, its relevance to your topic, and our need to unearth the roots of our cultural orientation was made clear. Was this breaking of the fourth wall a difficult decision to make?

Breaking the fourth wall was the easiest decision to make, to be honest. My biggest concern or worry was that the letter was not going to end up in the book because of the peer-review process or because an editor wouldn’t approve, but thank God neither of those things happened. My letter, and the traumatic experiences that forced me to write the letter, had been on my mind for years. The police interactions I had generated a lot of anxiety and fear within me. I always knew I wanted to publish that letter because every time I would share the story people would act shocked as if we (me and you, Claudia) don’t occupy precarious positions in this anti-Black world, one that is so full of misogynoir. As a nearly forty-year-old Black man I now know, having learned through other unwarranted, hostile police encounters that stole my joy, that having a PhD does not exempt me from experiencing racism. Once upon a time, I really thought, “When I earn my doctorate, people will treat me differently, better than the dirt they think I am.” But that was naïve. I know from your 2022 play Help that being a New York Times bestselling author, having a MacArthur Fellowship under one’s belt, and flying First Class do not exempt one from experiencing the effects of a world defined by white dominance and anti-Black racism either.

In their own ways, my parents are archivists. My dad held on to the police profiling letter I wrote after all these years. He put it and my book’s accompanying Appendix materials in a safe place. Perhaps he knew what I didn’t, that someday my letter would allow my adolescent pain to empower me, providing a little retribution for my seventeen- and eighteen-year-old-selves—the letter published in my own Cambridge University Press book that will soon be released as a Tantor Media audiobook narrated by me (I just couldn’t see anyone else reading my book, especially the Conclusion). The decision to include the letter was easy. And its inclusion came from a place of wanting to underscore problems of all kinds, in this case what it means to be driving while Black (D. W. B.) at any age or “doing while Black” as I reframe the phrase in the book. As I emphasize, there is not one thing in this world that Black people can do without experiencing racist violence of some kind—just recall the racially-motivated 2015 shooting that occurred at Charleston, South Carolina’s Mother Emanuel AME Church, where nine innocent Black people were gunned down during their Bible study. Even while peacefully in prayer we are not safe.

Dealing with the emotional and psychological effects of working so intentionally with the letter was the difficult part. With SWŌ, the shorthand name I, my Cambridge UP editor Emily Hockley, and the Cambridge UP Marketing Exec Emma Goff-Leggett use for my book, I was determined to write the Shakespeare book only I could write, and I say that humbly and with respect for the other books out there that I certainly could not have written. The phrase “book that only I could write” is a nod to my Trinity colleague Irene Papoulis’s insightful new book The Essays Only You Can Write that aims to dissolve the boundary separating the academic from the personal in writing. As you rightly note in your generous endorsement, Shakespeare’s White Others “reimagines the scholarly monograph mode” by drawing conscientiously on my critical-personal-experiential scholarly methodology that collapses the boundary between those three modes. Determining from the start that I wanted to end the book with the letter meant I had to figure out how to get there. How? That was the question, an important question because I wanted my readers to learn about a past moment in my life that significantly informed my book and to understand my desire to be an advocate on behalf of Black people who remain pigeon-holed at the bottom of the racial hierarchy partly because of the white other’s active presence in our modern world.

My final question has to do with your concept of the “racialized comedy of t(errors).” The alignment or attention to the existence of the word errors in terrors suggest a hope of reversal of these racialized dynamics because, as you point out, they end in hurting whiteness as well. Your rational call to “don’t hurt yourself” is full of compassion, but just as Shakespeare’s tragedies reinstate the system at the close of each play, do you think our drama is set? Is power always intended to overpower, as Neal Hall states in so many words?

I don’t think our drama is set in the long-term. I appreciate that my point there registered for you, as the bifurcated term “(t)errors” in my conclusion’s subtitle is doing heavy lifting. The subtitle as a whole plays on the name of Shakespeare’s play The Comedy of Errors. Beyond that, the parenthetical term in the subtitle considers the real terror linked to the Black existence because of the racist errors people make. While I believe racist actions are intentional, I still consider them errors because the behavior is morally and ethically wrong. I don’t use error to let racists off the hook; I do not cosign the idea that someone’s racist behavior is a “mistake” since actions are choices. Rather, I use error to signal the inaccuracy of their faulty, or ill, “white logic,” as Tukufu Zuberi and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva call it.

Less obvious about the phrase “comedy of (t)errors” is how it gestures toward Du Bois’s theory of double-consciousness that’s defined as “this sense of always looking at oneself through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.” I’ve always appreciated this definition; it has illuminated a lot for me over the years. And I value the phrase “eyes of others” even more now because others includes the “white other,” thus further revealing the complexity of double-consciousness. As for you and me and what we will see in our lifetimes: until all who subscribe to anti-Black racist practices realize and correct the errors of their ways, here we shall be, in the comedy of (t)errors with Neal Hall’s words on power ringing true.

I cannot speak for all critical subjects but when it comes to the drama being set in the short-term, however long that is, I think Black people are unfortunately destined to exist within “the dominator imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchal” comedy of (t)errors structure—I’m referencing bell hooks’ Black Looks there. To answer the other part of your question, I believe power is always intended to overpower within that particular structure. That’s how the system survives and reproduces itself. I don’t think it has to be that way, with power always overpowering. I don’t think it will forever be that way, but there’s a lot of work to be done globally in the name of fighting anti-Blackness and racism. We are not there yet. We are not even close. That is what I mean when I say you and I will not see it in our lifetimes. But I hope your daughter does. Should I have children, I hope they do, too. But for now the comedy of (t)errors stage is set. And like our Black ancestors, we, the players, must simply play on.

Claudia Rankine is the author of five books of poetry, including Citizen: An American Lyric and Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric; three plays, including HELP, which premiered in March 2020 (The Shed, NYC), and The White Card, which premiered in February 2018 (ArtsEmerson/ American Repertory Theater) and was published by Graywolf Press in 2019; as well as numerous video collaborations. Her recent collection of essays, Just Us: An American Conversation, was published by Graywolf Press in 2020. She is also the co-editor of several anthologies, including The Racial Imaginary: Writers on Race in the Life of the Mind. In 2016, Rankine co-founded The Racial Imaginary Institute (TRII). Among her numerous awards and honors, Rankine is the recipient of the Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry, the Poets & Writers’ Jackson Poetry Prize, and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Lannan Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, United States Artists, and the National Endowment of the Arts. A former Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, Claudia Rankine joined the NYU Creative Writing Program in Fall 2021. She lives in New York.

This post may contain affiliate links.