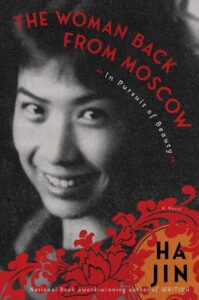

[Other Press; 2023]

Yomei and Jiang Ching are rivals in both love and art. In the course of a nearly eight-hundred-page novel that spans almost thirty years, this rivalry seems limited, at first, to a minor incident in Yomei’s life. In 1937, Yomei is a seventeen-year-old acting student at the Hsun Academy of Literature and Arts in the important Communist base of Yan’an, and Jiang Ching is a twenty-four-year-old instructor and actress, increasingly jealous of Yomei’s rising star. One day after class, Jiang Ching warns Yomei against starting an affair with another instructor, Yi-xin, because she wants to pursue Yi-xin herself. Jiang Ching admits she needs a man like him for the career advantages he could bring her and disparages Yomei for being naive enough to still believe in the “purity of romantic love.” Yomei departs for Moscow, leaving Jiang Ching behind. But Yomei and Jiang Ching are based on real historical figures, and those familiar with twentieth-century Chinese history will know that this early episode in the novel is an indicator of things to come. Yomei is popularly known as Sun Weishi, and went on to become the first female director of modern spoken drama in China. Jiang Ching is better known as Madame Mao: she became the fourth wife of Mao Zedong and a major player in the Chinese Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 70s. On October 15, 1968, Sun Weishi died in prison after seven months of torture and interrogation. Her arrest had been ordered by Madame Mao, who was presumably motivated by jealousy.

The Woman Back From Moscow is the tenth novel by Ha Jin, the pen name of Chinese-American poet and novelist Jin Xuefei. Jin grew up during the Cultural Revolution and served in the People’s Liberation Army before coming to the United States to study at Brandeis University. He has explained his decision to write in English as one motivated by the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989 and a desire to “preserve the integrity of my work” from China’s censorship laws. His audience is consequently English-speakers, but he has stated his hope that “literature can transcend language” and that his work will be valuable to a Chinese-speaking audience one day, too.

The universality of art is one of Yomei’s central preoccupations, as well. After studying the Stanislavski method in Moscow, she commits herself to adapting Russian works for a Chinese audience because she believes the “spirit” of Russian literature is centered on the question of “What should a good life be like?” and “even the revolutionary literature in the Soviet period still carried on the same essential exploration of the human condition.” Yomei is committed to the Communist cause but her stance on art is not always in line with the Party’s, though it does align with Jin’s own beliefs. Yomei’s time in Russia serves her well at first, when relations between Russia and China are positive and her use of Russian phrases in Mandarin, like “this [problem] is like a nail in my head that I can’t pull out,” are taken as a positive mark of her education abroad. But during the Cultural Revolution, Yomei’s ties to Russian culture and her plays’ subject matter are seen as “bourgeois.” A letter from one of her prison investigators, included at the end of the novel, notes a particularly shocking detail about her torture in prison: “a nail was hammered into the top of her head.”

Jin includes an overwhelming wealth of details about the politics, people, and cultural scene of the time in this exhaustively researched novel while centering the intrapersonal dramas of Yomei’s life. He tells readers early on—and then reminds us maybe too often—that Yomei is beautiful, charming, and talented, and this is the source of both her success and her interpersonal troubles. Unlike Jiang Ching, Yomei is singularly focused on her artistic career and shuns the notion of using men for protection or advancement. Despite her high-minded approach to romance, though, she can’t avoid the admiration of men and the jealousy of women.

Yomei’s personal entanglements come with high stakes: most of the people in Jin’s novel are part of the elite circles of China’s Communist Party, although they are also, of course, only human. As Perry Link pointed out in his review of the novel, chronicling such unflattering or petty details about these important historical figures contradicts the CCP’s often-idealized depictions of many of them, and is part of why the novel has only an English-language audience. Among the many historically existing characters in Yomei’s life are Zhou Enlai—her adopted father who became the first Premier of the People’s Republic of China (PRC)—and Mao Zedong, whom Yomei serves as a Russian tutor, translator, and companion to during his trip to Moscow. In Yomei’s world, a woman may rise to a high position in the art world, but she will always be expected to fulfill her primary duty to the party by taking care of a husband. Everyone around her sees marriage as a vital source of stability for a man, allowing him to focus his energy on revolutionary duties, and Yomei is often pressured to serve this purpose. But she is painfully aware that such marriages don’t offer similar stability to wives, who are often left behind or divorced in favor of a new lover. In this context, the toxic jealousy that dooms Yomei is somewhat easier to understand.

Yet, one of the most enduring relationships in Yomei’s life is with her best friend, Lily. Men never manage to come between them, in part because Lily has little interest in men in the first place. She attributes this to a childhood memory: while traveling by ship, she saw a man try to grope a woman and then, his advances rejected, abruptly push the woman overboard to her death. This served as an enduring lesson about the very real danger faced by women at the hands of men who assume they are owed women’s attention—a lesson many people are still struggling to learn today. As a consequence, Lily doesn’t begrudge Yomei the constant attention men show her, and the only thing that does come between them is her disapproval of Yomei’s eventual choice to marry a man who, in Lily’s eyes, is beneath Yomei. Without men serving as her admirers or protectors, Lily doesn’t rise to the same career heights as her friend, but neither does she face the same scrutiny or punishment.

Jin uses Yomei’s experiences as a director, who adapts works from Russian and American literature for the Chinese stage, to reflect on the purpose and nature of art. Although Yomei is never sure whether art can be separated from politics, she remains an adherent of the Stanislavskian method she learns in Russia: exploring characters’ inner motives instead of just showing their actions or outward emotions. Jin’s novel is, in many ways, an attempt to apply this principle to fiction by narrating the emotions and everyday experiences of historical figures, and he makes an effort to be sensitive to women’s experiences.

However, perhaps because he is tackling such a long period of time and meticulously detailing so many historical developments, Jin’s attempt to embody Yomei’s perspective often feels rushed, surface-level, or unconvincing—especially when it comes to her relationships with men. Early in the novel, Yomei meets the ex-wives of top party leaders, including Mao, in Moscow, where some of them have been committed to an insane asylum. Yomei concludes from meeting these women that,

Indeed, it was hard for a woman, no matter how energetic and intelligent and resourceful, to remain sound and sane in a strenuous struggle together with her man. Such a condition ought to be taken into account as an additional sacrifice for women to join the revolution. They should also conceive of the possibility of hysteria incited by their political zeal, by their shattered ideals, and by their men’s betrayals.

Yomei’s idea of “hysteria” as a particularly female condition, partly caused by the psychological challenges of the revolutionary struggle that men are assumed to weather just fine, doesn’t make sense to me. Her mother remained very much sane and strong-willed after working for the CCP’s underground, losing her husband, and living in exile. So do numerous other women in Yomei’s life. Why would she, as an “energetic and intelligent and resourceful” woman herself who resists the pressure to be subordinate to any man and witnesses men’s constant underestimation of women, doubt women’s equal capacities in such a fundamental way?

Yomei is twice the victim of sexual violence, and Jin seems to pull back from, or be incapable of, depicting her “inner world” in these moments. One night, while tutoring Mao in Russian and sharing drinks with him in his train compartment, Yomei is drugged and raped by the Chairman. Jin gives a jarringly surface-level account of Yomei’s reaction the next morning:

When she woke up before daybreak, her head was still woozy from the alcoholic fog. She was shocked to find herself lying next to Mao in his bed. She was half naked, without her underpants on. Mao was snoring lightly. She turned her head and wondered how this had happened. . . . ‘Why . . . why did you do this to me? You ruined me,’ she wailed in a quivering voice, still not daring to face him, her heart thudding in her ears. ‘I could tell you were not a virgin. I don’t like virgins anyway.’ He paused, then went on, ‘Please join my staff. I’ll be nice to you.’ He lit a Chunghwa cigarette and took a drag, then blew two tusks of smoke out of the edges of his mouth. ‘Let me alone!’ she cried out between sobs. ‘I used to respect you like an uncle.’ ‘But you’re a woman now, like a ripe plum. You’re sensuous and beautiful, much better than Jiang Ching. To be honest, I like you more.’

Until this moment, Yomei does not spend any time worrying about her feminine “honor,” or the sacredness of her virginity. So why is her first reaction to the assault this patriarchal idea of rape as “ruining” a woman for other men, and her second about how it changes her relationship with Mao? What about Yomei herself? In such moments, Yomei’s “inner motives” can feel subordinated to her outward actions and emotions. Jin and Yomei’s theory of the universality of art seems to show some cracks when it comes to balancing a convincing psychological portrait of Yomei with rigorously researched historical fiction. Yomei is in many ways a product of her time and place, and Jin painstakingly reconstructs this context for an English-language audience to whom it will be largely unfamiliar. But, as a result, some of Yomei’s “inner motives” may get lost in translation.

Hana Stankova is a PhD candidate in Slavic Languages and Literatures at Yale writing a dissertation on travelogues about Central Asia in the nineteenth century.

This post may contain affiliate links.