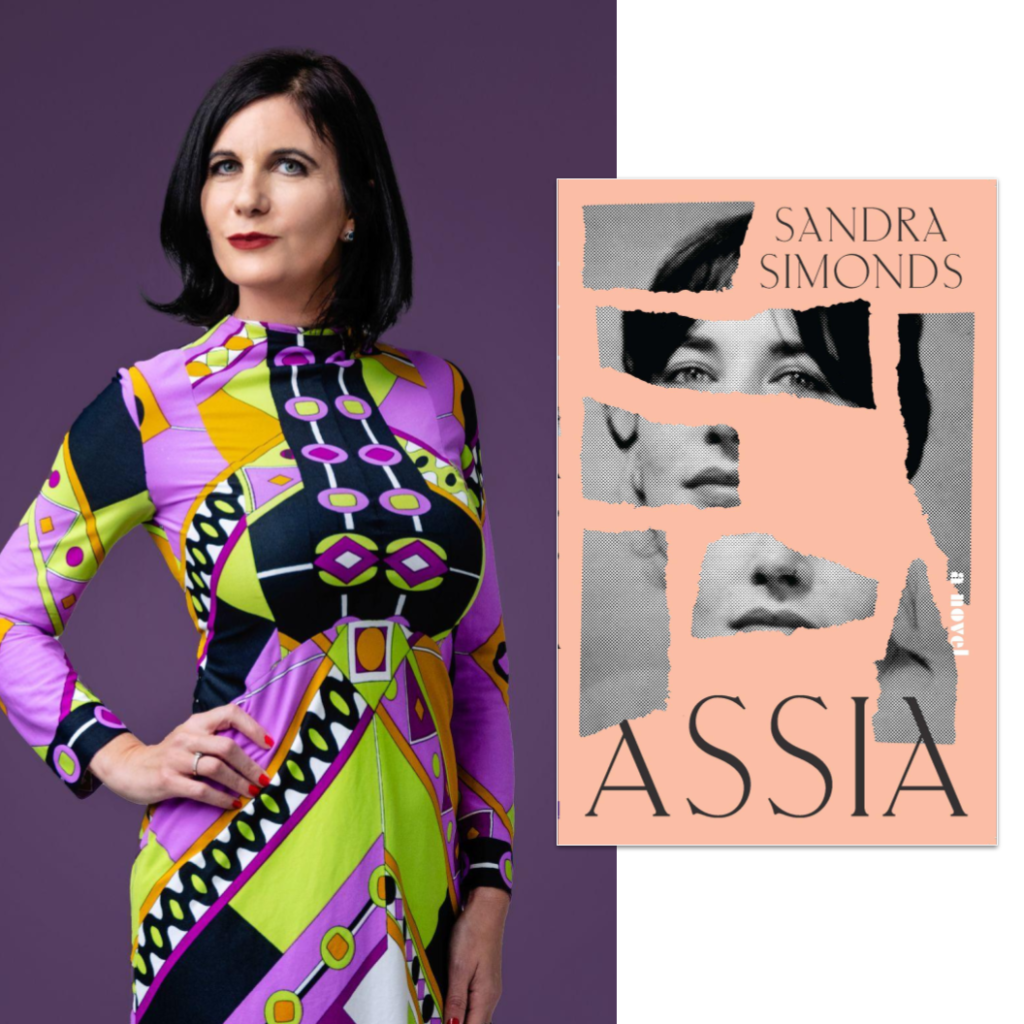

It is no small thing to grapple with the fraught legacy of cultural figures who loom large in collective literary imaginations, but Sandra Simonds, in her debut novel Assia has done so admirably. Assia is an imagining of the life of Assia Wevill, the second wife of Ted Hughes (after Sylvia Plath died), as well as the lives of those she touched. I spoke with Sandra over a video call, and followed up on email.

The following transcription has been edited for length and clarity.

Sophia Kaufman: It appears, both from historical accounts and from your own book, that it is sort of impossible to talk about Assia without talking about Sylvia and Ted. Can you tell me a little bit about when you first became interested in Assia as a figure in poetry/cultural history? Did you somehow know about her work before knowing about the other two? How did your interest evolve there?

Sandra Simonds: I knew I wanted to write a novel, something that wasn’t poetry, and I was looking for a subject, and then when I read about Assia—she’s sort of traditionally depicted as this mistress figure, she doesn’t have much personality, she’s kind of a stock character in that whole story, which is that she’s the destroyer of the marriage of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes. So I was interested in her because I didn’t know much about her. My friend who works at Emory, one of the rare archival librarians, said, “Oh, we have the Ted Hughes archive here, and the Assia Wevill archive,” so I had this vision and I followed it, and went to Atlanta to read through all of the archives, and I saw a picture of her, and I was taken aback because she looks a lot like me, which was weird! And so then it just happened from there. I was inspired by the archival material, she’s Jewish and I’m Jewish, so I think that was a really big part of her story, so I wanted to think of her as a Jewish twentieth century person who was constantly displaced from country to country.

What kind of materials were in her archives?

Letters to Ted, journals. . . Since I wrote the book, actually, her collected poems, translations, and journals have all been published, but they weren’t published when I wrote the book. Drawings, and then some mysterious witch crafty drawings and strange writing that I could never end up deciphering, but it did take on some kind of meaning in the book, because those sort of occult ideas became a part of the book too.

That leads to my next question! Throughout your book, Assia is beset by visions. Maybe you’ve just answered this, but I was wondering, what’s the narrative inspiration for them? Was it these mysterious “witchy” materials?

Yes, in part. I knew just from reading that one of the things that interested Ted Hughes about Assia was that he was also into the occult. He was into the cabala and other sorts of more esoteric sorts of things. I think he in some sense objectified her in that way; she was symbolic of this kind of otherness, he kind of believed she had kind of like magical powers. I’m also a poet primarily, so I wanted to use this vision poem thing to make her more interesting and then also to use some of my skills in poetry, and then to connect her more to Plath, to envision a different narrative of her relationship to this woman.

A lot of the writing in Assia is about the war in Assia and Shura’s “blood, bones, cells, and genes.” I’m curious: what are your thoughts on the discourse around generational trauma these days? It’s become a term that’s percolated past sociological and literary demographics and now is a pretty common thing to see discussions about, at least on my TL.

Yea. Well, for me it’s very personal. My mother is French, and my family were Turkish Jews who went to France, and my grandparents survived the Holocaust, so I think I have an intimacy with that history. I understand it in my heart and body. I think that for me, I was able to use my own experience with that, you know, as the grandchild of Holocaust survivors. My grandfather was a teenager was in the French Resistance; my grandmother was hidden on a farm. So I think for her, for Assia, I could understand on some level through my family experience what that is, what it means to be displaced, and then for all those feelings to sort of carry over from generation to generation and to feel it on a cellular level.

Ted, Sylvia, and Assia all have discussions about things being harder for artists, generally, and specifically emotionally, which is sort of a sentiment echoed not only by some artists throughout time, but also by many readers who love them. What do you think? What do you think it does when artists believe their own emotions are more tumultuous than everyone else’s?

That’s hard for me, since I’ve never been a non-artist. I think artists are sensitive people, so I think it’s harder on some level to get by, and then I think we live in a society that doesn’t really value the art, so there’s often competition between a job or taking care of kids, and then creating art, so then it never feels—unless you’re very wealthy I guess—you know, very few people can live off their art. I don’t know that it’s a competition between artists and not artists. I think of it as the self struggling to be fully realized in a society that doesn’t really appreciate the gifts of artists. Also, there’s a tradition of penury in poetry, and struggling to survive, and back in certain times you’d need a patron and aristocratic support, and now we have the university that sort of supports it, but that’s been in such rapid decline. So I think for poets specifically it’s always been a struggle. It’s always secondary for many many poets to economic survival.

Do you think poets these days still occupy the place of desire they used to? I feel like in your story, there’s this idea of poets being very desirable people, especially in Assia’s circle: She has that one friend who obviously is trying to impress her by sleeping with a famous poet, and literary celebrities, so I was curious if you think that’s still the case.

Well, Sylvia Plath became famous posthumously, Ted Hughes became much more famous later because he became the poet laureate. Robert Lowell had some level of fame, because he was on the cover of Life or Time or something like that. You know, this was within a very small artistic circle, either aspiring poets, or some poet wannabes, but whether they occupy the same place of desire now. . . I don’t know, that’s a good question. Their world was a fairly small, bohemian world, so.

Early on in the book, you have a section from Ted where he says quite bluntly that his actions helped make Sylvia into a legend. Do you think that’s true? Do you think he had a large role in making her what she was, or do you think she would have gotten there on her own? It’s unfair to speculate, but I’m always curious what writers who have grappled with the fraught legacy there believe.

You know, Ted Hughes is vilified, and to some degree rightly so. Like, feminists would go to his readings, after Sylvia died, even though this was just before, or just as the women’s movement was beginning. There’s some kind of tragedy there, like who knows if any of this would have happened ten years later, right. But getting back to Ted Hughes, I don’t know. There is myth-making in art, and it helps to have a villain, and Ted Hughes occupies that position. It’s possible that he helped to create the kind of understanding of Plath, or the mystery around Plath, that we have today. Yea, I think that’s fair to say. But not through the way he would say it, but through some kind of historical construction.

The role of gossip plays a huge part in your narrative, not only because Assia is obsessed, to a certain extent, with what people think about her and what people think and say about Sylvia, but because at the time, literary gossip seemed like a much more potent currency than it might today, maybe just because it’s that much more ubiquitous and the cycle is just so much faster. What do you think of the role of gossip in current contemporary poetry circles?

That’s a good question. Gossip has morphed into a much more marketed, highly capitalist sort of thing. What we would have called gossip, now has more of a currency, right—gossip has sort of morphed into a sort of Twitter milieu, and I don’t know if it would be called gossip anymore. I think that bracketing of understanding of particular poets, or that currency of knowledge, has greatly diminished, or taken a different form. Again, the way that information gets around—it’s a completely different world in terms of how quickly we know things. Like with Twitter, do we really want to know this poet thinks this, or is an anti-vaxxer, or whatever? Like I found out that this poet that everyone seems to love is actually an anti-vaxxer, but he’s not on Twitter: Is that gossip? It’s an interesting piece of information that, were he on that platform, might get him canceled or something like that. I feel like the way information circulates is much more tied with our highly capital lives, our capital world. Twitter is a kind of public, highly monetized form of our interior lives.

There are many parts of the story where Assia is addressing her thoughts to her daughter, and there are moments where Assia is talking about her daughter as if she’s already gone. Do you see your work in conversation with other writers who have had their narrators address their stories to dead children or have this sort of beyond-the-grave style?

The way that I began the book, it wasn’t like letters to the daughter, but then I had one or two in that form, and it seemed to work. I’m sure there are plenty of books like that, but I didn’t read any. There’s something about the idea of trauma passed down, and her final decision to kill herself and her daughter is about wanting the cycle to end, that’s the only solution she has, it’s the only way she sees forward. And I was just teaching the Uncanny to my students, you know Freud, and it’s based on this story by Hoffman, where he just has to throw himself off a tower because that’s the only way to end this repetitive trauma, and I think that that’s her thinking through and just kind of explaining herself, and just an act of love. It’s not murder with malice, even though of course it’s a terrible thing.

Sort of in a similar vein, you have this idea of a “ghost haunting your own story.” Are there other writers or narrators that you would describe this way?

I did read a book by Kate Zambreno about her mother. . . But I read mostly poetry—not a ton of novels. Honestly, I didn’t know how to write a novel. This is the first novel I’ve ever written, so I read things like The Notebook, and Elfriede Jelinek, Elena Ferrante, Christa Wolf, just to figure out the form and learn how to make people want to turn the page, just in terms of formal strategy and how to get these things to work. With poetry, you don’t have to think about someone needing to keep reading a narrative.

Assia, in your book, repeats over and over that she is nothing. I’m wondering; why does that belief loom so large to her, for you, in the book?

The fact that she feels like she’s nothing? I think because she feels like she’s a failure. I don’t think she’s super talented. I think she wants to be an artist, and my fear when writing this is of course was: Am I this person, am I her? And I had to keep telling myself no. But maybe the fear is there, somehow she either doesn’t have the attention or can’t commit to an artistic project, and she knows that, and she wants to be on the level of these people she considers great artists, and she’s failed, and she feels that deeply. So that’s why she says that, because she doesn’t have any feeling of self beyond other people. She relies on her beauty, and was known to say she didn’t want to live past forty because she wouldn’t be beautiful after that. It’s terrible to read that. It’s very sad.

Sophia Kaufman is a writer and editor living in New York. You can reach her at [email protected] or @skmadeleine.

This post may contain affiliate links.