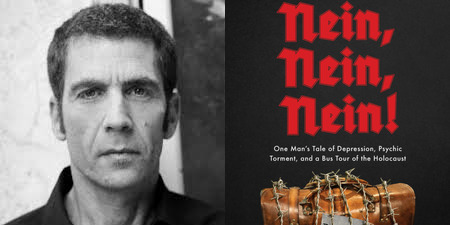

“I am visiting this place because I want to feel the dead,” writes Jerry Stahl in his new book, Nein, Nein, Nein! One Man’s Tale of Depression, Psychic Torment, and a Bus Tour of the Holocaust. “I had hoped, I admit, that coming here would make me a better person. Instead, I feel like the inside of my brain is sinking into viscous quicksand. Quicksand with piranhas in it, streaming on Twitch.”

Stahl’s book is, as the title describes, a bus tour of the well-known death camps in Europe which operated during World War Two. It is a bird’s eye view, maybe that of a buzzard, of how we react today in the face of one of the twentieth century’s greatest atrocities.

To comprehend such acts may leave you falling short of the appropriate awe of what happened here. How do you react to the story of a gas chamber full of bodies topped with children as their parents struggled to raise them to the fresh air?

The bodies are long gone, buried and burned, stripped of clothing, jewelry, and gold fillings, but their presence remains, strong as in life. The world has not forgotten them, nor will it ever.

It is against this backdrop that Stahl checks the context of his own depression and how his fellow bus riders match up against the “greatest crime of the twentieth century.”

I talked with Stahl online recently about his new book, and what it’s like to be mistaken for Kramer.

David Breithaupt: What do you anticipate the reaction to your book might be? We are back in the age of banned books. Do you hope to achieve that high status?

Jerry Stahl: I never think about the reaction to my work. Most often, as a writer I’m happy if there IS a reaction. Past books—if that’s any indication—have induced everything from vomiting to death threats. (Not to brag.) And, in the case of my first book, Permanent Midnight, I was blamed (credited?) with everything from helping people get off drugs to driving them to the nearest needle. Which is a longwinded way of saying you never know. Because of the Holocaust—or Holocaust-adjacent—nature of the subject matter, I imagine there will some who interpret my reaction, say, to the calzones at Auschwitz as disrespectful. Or all the personalization and identification—wondering if the savagely tormented souls in the camps thought about (were obsessed by) the same dumb shit you and I are; regrets over past mortifying behavior, over legions of blown opportunities, or the shame-packed nature of failed relationships, and so on down the laundry list of neurotic self-obsessive behavior. Or were they, thrust into this hellish new reality, instantly relieved—if relieved is the word (which it probably isn’t; maybe “shorn of” is better)—of the petty vagaries and torments of their pre-camp existence. Stripped instantly of all concerns but immediate survival, the brutal burden of even comprehending the details of this horrific new reality, what happens to an individual’s soul and psyche?

Mind you, after the six-part Vice series that served as the germ of the book, I did receive the odd smattering of hate mail. One of my heroes is the brilliant—and fearless—cartoonist Eli Valley, who lives with a level of hatred and self-righteous vitriol aimed his way that I cannot even imagine living with. There is a price to be paid for telling a certain kind of truth. In a certain kind of way.

But being banned? They have to have heard of you first. And literary cult act that I am, not sure that’s going to happen. But hey, a guy can dream….

It’s difficult for anyone today to truly comprehend the horror of the death camps. Were you surprised by the reactions of your fellow tour riders to the camps as well as the tourists in general, taking selfies in Auschwitz?

Very little in the way of human behavior surprises me. But, no, I was not expecting selfies at Auschwitz.

To make it worse, in my case, a group of young teen girls with a selfie stick happened to mistake me for Michael Richards, a.k.a. Kramer, and wanted to have a selfie taken with me. I mean, what is the etiquette for taking a selfie with teen girls at a death camp, all of whom think you are a celebrity, when you are NOT that celebrity? Sadly, it is a topic never covered by Emily Post. (Who was of course pre-social media.)

My own bus crew were a respectful bunch. If you can get past the fact that many seemed dressed for a weekend at Disneyworld. Then again, who, really, am I to judge? I’ve been wearing the same black tee-shirt and black jeans for nine hundred years. As there is no dress code for mass death visitation, I suppose my surprise at the odd Daisy Dukes or Megadeth tee says more about me than the humans on hand.

As a rule, there was not outright weeping at the camps. What there was is something I came to call Genocide Glaze. A kind of blank hollow in the eyes, some look beyond grief, or terror, on into the darker regions of pure, numb, inescapable awareness: What happened here happened, and, for those of more thoughtful or informed persuasion, is still happening.

On the other hand, what do you wear to the greatest crime scene of the twentieth century?

But, back to your original question, inasmuch as selfies stand out as the defining mode of personal expression, it would probably be weird if people weren’t taking them. It’s not like the gift shop was selling I WENT TO AUSCHWITZ AND ALL I GOT WAS THIS STUPID TEE-SHIRT! It’s nice there was a modicum of dignity.

You wrote in your book that it’s not the Holocaust that is exceptional, but the time between them. I can’t help but to think of the gun violence that has afflicted our country and that the time between such tragedies is becoming shorter and shorter. What happens when we no longer have time in between?

That is a very good question. And I think we have, already, reached the time when there is no time between.

For somebody, somewhere, at any given time, the axe is falling. I no longer think it is a question of when, it is a question of how.

To take our own country: for, say, a simple poll worker in Georgia, life has become a living hell as MAGA-loids have taken to nightmaring her, and her elderly mother, to the point where this poor woman—whose crime was daring to not put her thumb on the scale for Trump—can no longer go to the fucking grocery store without strangers screaming her name or chasing her down the street like she is the spawn of Satan. Her life is, effectively, ruined. And if there is a better definition, on the ground, of how fascism works, I don’t know what it is. (Unless perhaps it’s the insane online threats against the January 6th Committee, from the Trump is Jesus wing of American mania.)

And yes, by the time this is interview is posted, this information itself will doubtless feel quaint and jaded. But that’s the point. The Future is here, it’s shit in our face, and we’re calling it pudding.

Did your tour provide a new context for your own depression, or shift your view on humanity in any way?

The great sad beauty and wisdom, when you strip everything away at Auschwitz, Buchenwald, and Dachau, is that none of your problems matter. Your depression doesn’t matter. Your despair doesn’t matter.

In fact, in honor of your question, I may do something I never do, and quote the Dalai Lama, who said in the tail end of the 80s: “Happiness is the last radical act of the twentieth century.”

By that, in terms of the horror show in Poland and Germany, I take him to mean that nothing is served by adding your own misery to the Nazi-induced misery that preceded it.

Fuck them. LIVE.

David Breithaupt has written for The Nervous Breakdown, Rumpus, Exquisite Corpse, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and others. He has worked as a bibliographic assistant to Allen Ginsberg, a newsstand checker for Rolling Stone, and a staff member to the great Brazenhead Bookstore in New York City. He currently works for two sports newspapers in Columbus, Ohio, covering the Cincinnati Reds and OSU collegiate sports. Recent writing can be found in One Last Lunch: A Final Meal With Those Who Meant So Much To Us, The Columbus Anthology, and on Storgy.

This post may contain affiliate links.