This essay was first made available last month, exclusively for our Patreon supporters. If you want to support Full Stop’s original literary criticism, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter.

“That’s my answer to the question what is your strongest emotion, if you ever want to ask me: Curiosity, old bean. Curiosity every time.” – Sally Jay Gorce, The Dud Avocado

Elaine Dundy may have been the most well-loved, fame-adjacent person you’ve never heard of. She was in acting class with Tony Curtis and Harry Belfonte; she had a part in Yerma alongside Bea Arthur. Orson Welles, a close friend, helped her decide she needed a divorce from her bummer of a husband Ken Tynan, one of those talented people she described as “Destiny’s Tots.” Gore Vidal read and gave advice on everything she ever wrote. James “Jimmy” Baldwin taught her daughter Tracy how to do the twist, and read aloud his first iteration of The Fire Next Time in their drawing room. Katharine Hepburn was Tracy’s godmother. Dundy was the recipient of Christopher Plummer’s commentary at awards dinners (he approved of Mary McCarthy) and ran away with Vivien Leigh from dinners with their husbands to put on records and play with Vivien’s perfume collection. Miles Davis gave her advice on her novels (“slang dates fast”), even after she accidentally brought his wife Fran to a Hollywood orgy. Unlike many of these people, she had no interest in making her own voice known in a literary sense until someone else suggested it, and yet her novels are some of the most vibrant and enduring books I have ever found.

Elaine Brimberg (Dundy is a name she took on later in life, also at the suggestion of a friend) grew up on Central Park West. Her family, in clothing manufacturing, lost money in the stock market crash, moved, suffered, and then made it back to Park Avenue, while dealing with anti-semitism aimed at her and her sisters and their father’s abuse. When she was older and began daydreaming about the life she wanted, instead of imagining a love story or fame and fortune, she would imagine doling out advice to her idols; she liked the idea of giving them the benefit of her original opinion. (She wrote a lot of letters to celebrities in her adolescence). After transferring to Sweet Briar from Mills College, she did some war work as a cryptographer, felt important about it, had sex, felt good about that until she didn’t, called the guy later to berate him for making her a slut, and then decided it made her worldly. She studied at the Jarvis Theater School in Washington and worked as an actress, sometimes at the Dramatic Theatre Workshop in New York. Shortly after meeting Ken Tynan while living in London, she wired her family: “Have married Englishman. Letter follows.” After noticing that some stories she told at parties about her time in Paris made people laugh, she began to write a novel; her protagonist was created out of a desire to demonstrate the kind of parts she would have liked to play on stage, instead of the uninspired options being offered to her. The Dud Avocado sprang into being as if fully formed.

The narrator Sally Jay Gorce, much like her creator, views herself not as one of the socialites she weaves her way through, but a spectator, a scientist “dropping into the view at feeding time” as an American in Paris, a city she later describes as “one big flea bag.” When observing a group of artists, she thinks, “A rowdy bunch on the whole, they were most of them so violently individualistic as to be practically interchangeable.” She has a compulsion to write on steamed mirrors, hates champagne more than anything except seven-Up, and makes finger guns at the married man she’s having an affair with when he berates her for having been such a cynical virgin. When she is taken for a prostitute at a prostitute’s bar, it reminds her that to her perpetual disgruntlement she is commonly mistaken for a librarian when at a library. (Later, fresh out of schemes, she actually attempts to become a librarian, believing it would restore some sort of cosmic balance.) The book begins with Sally falling in love with an acquaintance after a drink with him:

[. . .] began studying Larry closely. . . . Maybe because I had been out very late the night before and was not able to put up my usual resistance, but it seemed to me, sitting there with the sound of his voice dying in my ears, that I could fall in love with him. And then, as unexpectedly as a hidden step, I felt myself actually stumble and fall. And there it was, I was in love with him! As simple as that.

Moments later she panics, remembering the lover she had actually been on her way to meet when she stumbled into Larry. Larry tells her the only reason she ever fell for this other guy is because she’s got no inner peace. She doesn’t disagree, much later observing, “That’s the story of my life. Someone’s behavior strikes me as a bit odd and the next thing I know all hell breaks loose.”

Sally goes away with Larry and some other friends – including a girl he’s seeing – to be movie extras, only to find out that one of her ex-lovers was correct in his assessment of Larry’s surprising true intentions and she needs to escape. The novel is brimming with observations about how people behave when abroad, at parties, sitting down to dinner, and when recoiling at the unattractive underbellies of the truths that make up their lives. It was an instant hit. Groucho Marx wrote to her: “I had to tell someone and it might as well be you (since you’re the author) how much I enjoyed The Dud Avocado. It made me laugh, scream and guffaw. If this was really your life, I don’t know how you got through it.”

As The Dud Avocado took off, the cracks in Dundy’s marriage began to widen. After confessing his predilection for sadomasochism, Tynan convinced her to try it, suggesting that if she didn’t, some other girl would. She acquiesced, but the episode ended with her breaking his cane over her knees, outraged, as she felt cheated out of a good lay for the first time in her entire life. (Later, when she tells another famous English critic about it, he replies, “of course Englishmen love flagellation, it’s the only time they ever get touched as children.”) Tynan grew increasingly uncomfortable with her success as a writer, as she recounts in her memoir: “One night he said to me coldly, ‘if you ever write another book, I’ll divorce you.’ That did it. Early next morning I sat down and started a new novel.” When she decided to leave him, he brutally assaulted her in a hotel room. They divorced in 1964, though they remained in each other’s lives.

Everything Dundy did, up to and including her fiction (not to mention the way she conducted her marriage, its fallout, and her sex life in general), was influenced by the screwball comedies of the 1930s and 40s. These films upended traditional love stories and vivified their quick-witted heroines – played by Rosalind Russell, Katharine Hepburn, and Barbara Stanwyck, among others – by allowing them to play out the battle of the sexes in ways that slyly let sexual tension manifest in saucy predicaments not prohibited by the Hays Code. From a young age, the ethos of the screwball was a part of Dundy’s life: “When Ava Gardner turned up at our flat in the rain needing to borrow money for a taxi, holding a piece of broken umbrella in each hand and explaining that she had broken it over the head of her lover, Walter Chiari, this was to me, purely and simply, acceptable screwball behavior.” Dundy was going to nightclubs by the age of 15 and taking her top off while standing through the sunroof of the cars speeding down the avenues on her way home, not for any attention, but because it felt like the right thing to do at the time. Her messiness was a kind of desperate chancing buoyed along easily by godshots, good luck, and charming celebrity screwball friends.

Likewise, Dundy’s heroines are all screwballs of the first degree. They drive the stake of their publicness through the heart of their circles – never afraid to cause a scene, never inclined to leave one early. They are obsessed with how they are perceived, but only in sporadic flashes, when acutely aware of a crucial moment in which they must perform, or else kiss their fiendish aims – vengefully seducing a man, stealing an inheritance, instigating a riot – goodbye. They’re so wrapped up in schemes that everything else comes second, and much like Tinkerbell in the original Peter Pan, they occasionally only have space for one emotion at a time, be it love for a man entirely unsuitable or guilt about planning a murder. They’re charmingly delusional. They have a spritely practicality. They all wear their mistakes the same way, hiding them when it’s possible, but archly throwing them in people’s faces like a drink on a dare when it’s not. No matter what decision Dundy’s heroines make, some dashing young man ends up verklempt on her doorstep, either kicked out by the chest or begging to be let in. Her stories – The Dud Avocado especially – sometimes feel like Kay Thompson’s Eloise grew up and skipped across the sea.

If the heroine of her first book was an exercise in screwball behavior and a fizzing outlet for the charismatic voice in her head, the narrator of her second novel, The Old Man and Me, was a direct challenge to the male antiheroines of the time, written by the cohort of writers Dundy referred to as the Angry Young Men. This protagonist is determined to take back an inheritance that she believes is rightfully hers, and unleashes a swarm of lies to get it, beginning with telling everyone in London that she is an heiress named Honey Flood. She engineers a relationship with a rich old Englishman named C.D. McKee, who, she realizes to her dismay, she finds equally attractive and repulsive. Their relationship – which borders on illicit, as he doesn’t know about her complex relationship with his late wife – is hilarious, continuously surprising her with her own passion for this “foxy grandpa.” Honey’s inner monologue, like Sally’s, make for an intriguing analysis of any occasion; this novel too is overflowing with nuanced observations, like how to spot the poorest person at a dinner party: “too much good taste, too much spartan simplicity disguised as Pose – my own game, in fact.” Unlike Sally Jay, Honey may not be a particularly likable person, but her dogged drive to get what’s hers is hard to peel your eyes away from. Dundy pulls off ending this book with a question in a way I’ve seen few writers ever successfully do.

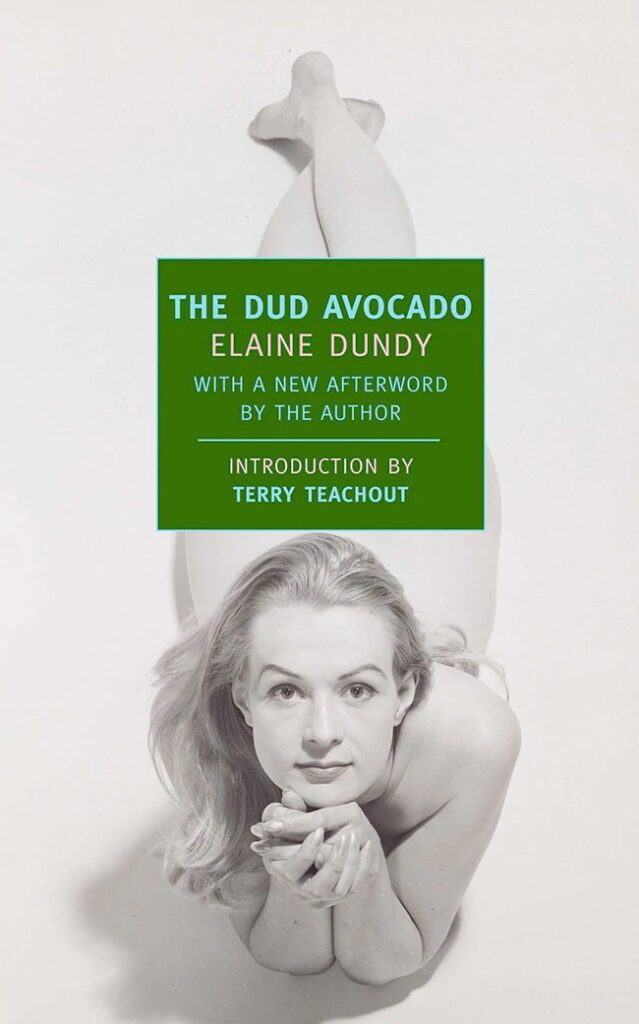

Dundy’s first two novels are easily accessible in the U.S., as New York Review Books keeps them stylishly in print. Her third novel, however, proved difficult to find, and I ended up ordering a battered little copy from a bookshop in the U.K. (The same can be said for her nonfiction books, Finch, Bloody Finch, Elvis and Gladys, and Ferriday, Louisiana, which are similarly difficult to track down, and her plays, which never saw as much success.) The Injured Party might be her most ambitious novel of the three, thematically and stylistically.

The protagonist, Rilla, works for her uncle at a newspaper; when he dies, she marries Arthur, the man who replaces him. Her marriage divides her from her best friend Terrence, who is convinced that her new husband has a shady past, and so Rilla throws herself into the supposed perks of being a married woman, such as her now unending social circuit: “They went everywhere and anywhere quite indiscriminately. If you asked them you got them. They met everyone. They drank, got sick, switched to pot, found that except for interestingly scrambling up their spatial perceptions it didn’t do anything for them, switched back to drink again adding Dexamyl to the mixture, went crazy, stopped, swore off drinking, swore off parties, looked at each other for a week or two and filtered back into them, stepping up the pace even more.” (This lifestyle was very familiar to Dundy, who had addictive tendencies she wrote about quite freely in her memoir.)

When Rilla’s husband ends up dead – through no real fault of her own – and she is put on the stand to be questioned about it, she refuses to tell the jury about her husband’s sexual perversions (slyly similar to Ken Tynan’s tastes) on top of his abuse because she is too put off by the salacious way the the judge, jury, lawyers and guards are all leaning forward. She can’t stop being funny on the stand either, which doesn’t help her case, and ends up sentenced.

The second half of the novel is an unbelievable romp through a women’s facility that feels almost inappropriate to be reading now, though much of it came from Dundy’s extensive interviews with people in a women’s prison. In Rilla’s facility, women move up to different cabins with privileges depending on their behavior; she immediately notes that many of the women look and act like men, a curiosity she regrets voicing as she instantly becomes of interest to the main butch inside, Kelly, who is eventually successful in wooing her. What follows is something akin to a queer awakening. Though Rilla doesn’t believe herself to be like Kelly, she enjoys the sex, protection, and social status, as well as experimenting with her gender presentation (almost to the extent that Kelly won’t sleep with her anymore because she looks so much like a man — but she gets over it). However, Kelly isn’t the only person Rilla is after — not when there’s a charismatic, do-good warden who hires Rilla to be his secretary, secretly hoping that she’ll eventually remember the first time they met, during the height of Rilla’s debut into society.

The Injured Party is the most experimental of Dundy’s novels; occasionally, the narration splits off and begins crooning to Rilla, urging her to figure things out, to feel them, to let go and let be, like right after she gets engaged: “Go, Rilla, go round. Feel for once in your life in the majority. Notice for the first time, almost the whole female world wearing wedding rings. . . . Quit your job at Panorama so that you can idle up and down the escalators of Bloomingdale’s, furnishing the huge apartment sometimes in your mind, sometimes – those lucky other times when you can get hold of a salesgirl and she is willing to sell you something to match your baroque, velvet, glass and gold mood – try getting it actually furnished.” It’s also the only novel of hers to go far beyond her own purview. She had never been in jail, but there is a surprising amount of tenderness given to all the characters in this book. As in her other works, race isn’t absent in her fiction, but approached as a matter-of-fact element of life that she could always learn more about, and The Injured Party reflects this attitude. And, as far as we know, Dundy wasn’t queer (though the way she describes Carson McCullers roosting on the arm of Marilyn Monroe’s chair at a party had me wondering: “…blond Marilyn Monroe was seated in an armchair. On one of its arms perched Carson McCullers, her brown hair chopped short and uneven as if she’d taken an ax to it, her body fierce in tomboy tension and twisted like a pretzel. Sitting in a chair on the other side of Marilyn-in-her-slip was Edwina-Williams-in-her-hat. They were conversing with each other, all three with heads inclined. The Three Fates, I decided; Beauty, Brains, and Motherhood. Whose destiny were they spinning out at that very moment?”).

Dundy’s novels are timeless because they are hilarious, well-written, and full of youthful glamor, but they also feel like they fill a void. Several popular fictional heroines these days, when bold and brash in the streets and the sheets and everywhere in between, are so either in pure defiance – balking at the need to over-identify or pathologize or defend or desist, clutching wildness around them as if it will liberate them from an environment that has grown to accommodate it — or as a bit, a sexy gimmick that they can wickedly perform in front of their readers, aiming to always be just out of reach. They don’t quite make it. Contemporary novelists more often than not bypass the screwball in favor of the sexy depressed hot mess, who is usually also incredibly aware of self and situation.

Perhaps part of the reason we’ve gravitated to this kind of heroine is because she fits easily into the defensive stance adopted, if subconsciously, by novelists who write as if they need to preemptively protect themselves from critics who could tear them down for not being self-aware enough, not understanding that life is worse for many kinds of people not featured in the book, or not being self-effacing enough inacknowledging that publishing is an insular game. They write as if they must mitigate other people’s reactions before they have a chance to have them. This issue in turn is conflated by critics with the idea that writers actually believe that solely by making their characters “self-aware,” the characters themselves are neatly absolved. Katy Waldman touches on this phenomenon in The New Yorker, in an essay where she says that “Rooney, like her characters, seems content to perform awareness of inequality, even to exploit it as a device, but not to engage with it as a profound and messy reality.” So does Larissa Pham in the essay “The Limits of the Viral Book Review,” in which she ponders Waldman’s impulse, shared by other critics, to wonder how much of the myopia of the characters reflects the author’s own weaknesses.

Waldman is right that “pained complicity” has become a legible shorthand for authenticity in writing. But she falls into the trap of thinking that the writers she mentions (including Sally Rooney and Naoishe Dolan) purposefully write characters whose self-awareness absolves them from accountability. That’s not true. Plenty of people in my real life go through and tick off their privileges, identities, or current existential crises before any assertion they make in any number of conversations. Some probably do believe this absolves them from any further action; but I think for most, it just feels like a required gesture through which they’re actually asking listeners to trust them to be acting/writing/musing in good faith. This gesture is not indicative of a failure to engage with the messiness of inequality; it’s an early part of that engagement.

The only people who do this are those who, having spent enough time online, know just how many readers and critics there are who will gleefully read anything into a paranoid oblivion and publish their diatribes. This new kind of anxiety of authorship is present in book criticism, as a lot of critics write like they must prove to readers they know exactly who and what are not in the novel they’re reviewing and why, on all levels, instead of just reviewing the novel on its own terms. I think this especially affects new critics, whose writing often suggests a sense of need to prove themselves that more established writers don’t have – perhaps because they built their readership and reputation before Twitter (and thus the “viral book review”) was such a hotly debatable digital commodity.

All of this is to say, Dundy’s novels fit our times well while also existing blissfully without any of this baggage. Dundy’s characters are often selfish and reckless, but there’s nothing forced in these stories — not the characters’ negative qualities, nor their awareness of them, nor their mitigation of how others might perceive them. Two of Dundy’s three novels involve women at least thinking about killing the men they’re involved with, but somehow there’s very little that’s dark and twisty about them. Her protagonists don’t think with their head nor their heart, but with their gut, following instincts like they never learned not to. Dundy wrote in her memoir: “intuition, I have always believed, is really reasoning speeded up.”

There are a lot of patterns in publishing now that could prime the way for more screwballs like Dundy’s in U.S. fiction: an exasperation with the navel-gazing and self-awareness in any form, a professed desire by editors and agents to see more submissions featuring Black protagonists that aren’t brimming only with trauma, a growing rejection of the electoral system and the cultural pillars it relies on in favor of immediate forms of aid and community, a growing exhaustion (I hope) with the glamorization of ironic sexy dark messiness, a snowballing exasperation with the cult of readers who approach “consuming” art first and foremost as a moral responsibility with its own set of rigid, crowd-sourced rules – the list goes on.

It might be cheap to end an essay with the subject’s own words, but one of Sally Jay’s sentiments is what I want to leave with, because I think she and I are hoping to cultivate the same perennial talent, and forever running up the hill of the same frustrations:

It’s just that I know the world is so wide and full of people and exciting things that I just go crazy every day stuck in these institutions. I mean if I don’t get started soon, how will I get the chance to sharpen my wits? It takes a lot of training. You have to start very young. I want them to be so sharp that I’m always able to guess right. Not be right – that’s much different – that means you’re going to do something about it. No. Just guessing. You know, more on the wing.

Sophia Kaufman is a writer and editor living in New York. You can reach her at [email protected] or @skmadeleine.

This post may contain affiliate links.