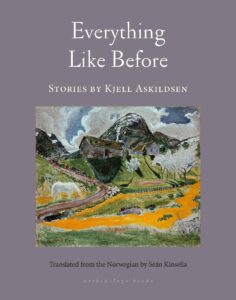

[Archipelago Books; 2021]

Tr. from the Norwegian by Seán Kinsella

When I told my Introduction to Fiction students that Kjell Askildsen’s stories were hilarious, I may have oversold him a bit. Not that I don’t think they’re hilarious. They often are. I just should have realized that this Norwegian’s dark, tense, minimalist stories full of inscrutable glances and ominous silences might be an acquired taste. But after I had my students read aloud some sections of “The Dogs of Thessaloniki,” one of the many disturbing domestic dramas in his collection Everything Like Before translated by Seán Kinsella — well, the room didn’t exactly erupt with laughter, but there were smiles and chuckles appearing among the sea of formerly blank faces.

It’s true that the premise in “The Dogs of Thessaloniki” doesn’t scream comedy: a miserable couple spends the day sitting around being miserable. But the narrator’s paranoia, suspicion, and the powerful revulsion and attraction he feels for his wife makes it a gripping and, of course, funny read. But the comedy has an edge to it, a threat. Each terse exchange is crackling with menace. The narrator simmers with rage, both at his wife for inferred alcoholism and suspected adultery and at himself for staying with her. Take this pleasant chat during dinner after, despite the wife’s morning prediction, it hasn’t rained:

I said: It didn’t rain. No, she said, it held off. I put my knife and fork down, leaned back in my chair and said: You know, sometimes you irritate me. Oh? She said. You can never admit that you’re wrong, can you, I said. I certainly can, she said. I’m often wrong. Everybody is. Absolutely everybody is. I just looked at her, and I could see that she realized that she had gone too far.

The narrator seethes all day about something as inconsequential as a conversation about the weather! He obsessively reads into every little word and gesture. Her dismissive “oh?” is fantastic. It can be read as mild surprise because his irritation, despite his attempts at stealth, is obvious. Or is its casualness a soft but nonetheless strong rebuke of him, his suspicions, and any attempts he’s making towards being in control? The comic tension is heightened in the self-seriousness he displays when putting his knife and fork down. And that “sometimes”! As if he didn’t just spend the day one moment wishing her dead and the next full of lust while tiptoeing around the house to spy on her.

Askildsen’s particular gift is the subtle way he imbues these mundane moments with so much frustration and rage, which creates an atmosphere of electric disquiet. The conflicts in each story always threaten to boil over. The silences are violent. The simplest glance is full of disdain, as demonstrated in this back-and-forth between the couple in “A Lovely Spot”:

He looked at her.

“Why are you looking at me like that?” she said.

“I’m just looking at you,” he said. “Cheers.”

That “cheers” simultaneously gave me chills and made me laugh. Is his look full of contempt for her, a reflection of his self-loathing, or both? Or does it portray even darker, perhaps murderous, desires? Later, when they’ve gone to bed, the chasm between the couple they appear to be and the utter strangers they really are, is made visible:

She was asleep. He undressed and crept under the duvet. She was lying with her back to him. After a while he placed his hand on her hip. She gave a low moan. He left his hand there. He felt his member grow. He moved his hand a little further down. Her body gave a start, as though from an electric shock. He withdrew his hand and turned the other way.

Growing members? Don’t pick up Askildsen for steamy sex scenes. If anything, his writing is anti-erotic. These two people exist together yet remain strangers. Maybe even strangers to themselves, alienated from their bodies, with their desires a million miles apart. The woman is even haunted by an Other made manifest in a man she sees hanging about their property and watching them. Is this man really there or is he a figment, a Dostoeyevskian double, the real version of her partner, or a creepy stalker, threatening and forever unknowable?

The slow burn of “A Lovely Spot” builds until the narrator’s one moment of outright physical violence, albeit even this is half-suppressed. The man drinks two bottles of wine and enters their bedroom:

She was lying with her back to him. She did not move. He went over to the closet and took out a woollen blanket. Mothballs fell down onto the floor. He slammed the closet door. She did not stir. He tugged the duvet off her.

“Martin!” she said.

“Just lie there!” he said.

“What is it?” she said.

“Just lie there!” he said.

Then he left.

What are we to make of this? Like many of Askildsen’s characters who struggle with the problem of other minds, by tearing the duvet off his partner, is the narrator symbolically trying to remove any veil between what she’s actually thinking and what she says? Or is it just petty revenge, something to unsettle her, to ruin the sense of hominess she has in this lovely spot? I’m not sure and my uncertainty, which occurs through the collection, is what keeps me reading. Askildsen’s minimalism, making the tugging of a duvet feel like an act of tremendous brutality, comes alive in that uncertainty.

Some of the stories are less darkly comic than just plain dark. Many aren’t centered on couples but revolve around self-lacerating varieties of miserable Underground Men. “A Sudden Liberating Thought” features a narrator who lives in an actual basement and doesn’t venture out until “One day while I was standing by the window, and had just seen the lower part of the landlord’s wife go past, I suddenly felt so lonely that I decided to go out.” This story is also notable for its defamiliarization, another skill Askildsen employs. Men don’t get erections; their members grow. This narrator doesn’t notice his landlord’s wife’s legs but her “lower part.” In Askildsen’s worlds, sex exists but promises neither pleasure, intimacy, nor connection.

In “A Sudden Liberating Thought,” the narrator is a disgraced doctor who served time in prison for assisting patients with illegal euthanasia. He’s also a misanthrope, which complicates his motives: was he actually alleviating his patients’ suffering or snuffing out lives because he’s convinced of the worthlessness of life? These questions come to a head when he befriends another lonely old man sitting on a park bench who is later revealed to be the judge who sentenced him to prison. Their conversations lead the narrator to the realization, to the sudden liberating thought, that he wants to die. He will no longer wait for Godot. The story ends with the disgraced doctor committing suicide. His only regret? “Why didn’t I do this long ago?”

So, perhaps the bleak is more dominant throughout the collection than the comic. Though I promise the comic comes through, such as in this exchange between a controlling, philandering husband and his formerly meek wife in “Sunhat”:

“You remind me of my dad,” she said.

He made no reply for a while, then said:

“I thought you liked him.”

“Did you? Well I was fond of him.”

That “fond” reminded me of The Comedians in Cars episode when Jerry Seinfeld picks up Larry David and asks him if he’s excited — to talk with an old friend, go for a drive, get coffee, do the episode. And Larry replies, “I wouldn’t say I’m excited but I’m looking forward to it.”

The stories in Everything Like Before are a blend of the comic and the tragic, then, told in prose made taut with unrelenting tension. The anecdote the wife relays in “The Dogs of Thessaloniki” might serve as an overarching metaphor for the characters that seethe and spy and suffer throughout the collection:

Do you remember the dogs in Thessaloniki which were stuck together after they had mated, she said. In Kavalla, I said. All the old men outside the café yelling and carrying on, she said, and the dogs howling and struggling to get loose from each other. And when we left the town, there was a thin new moon like that one, lying on its back, and we wanted to make love, do you remember? Yes, I said. Beate poured more wine in our glasses. Then we sat silent a while, for quite a long time.

While these howls — and the strained silences between them — resound most loudly from Askildsen’s chorus of characters, readers might hear a laugh or two in the refrain.

Kent Kosack is a writer, editor, and educator living in Pittsburgh, PA. His work has been published in Tin House (Flash Fidelity), the Cincinnati Review, the Normal School, Hobart, and elsewhere. See more at: www.kentkosack.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.