The following is from the latest issue of the Full Stop Quarterly. You can purchase the issue here or subscribe at our Patreon page.

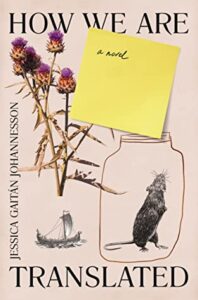

[Scribe; 2022]

What language would you speak to your children? For many, such a question may sound nonsensical as the answer would be rather straightforward. If you have always understood the world through a singular accent, there is no debate over what language you will pass on. If, however, you grew up between worlds, the public and the private spheres you occupied differing in what idiom was spoken, things become much more complicated. At the thought of future generations, the uncertainty of whether to share your native tongue with your children arises, and, along with it, a hint of fear if they will even care to learn it.

Some say that one’s native language is the first thing lost in the immigrant experience. While food can last generations, familial bonds growing stronger over the dinner table, tongues are quickly forgotten. There can be many reasons for this. On the one hand, The pressure to assimilate may result in parents insisting their children grasp the unfamiliar culture. In this case, success is understood as being directly linked to the younger generation’s mastery of the new language, and, for that to happen, the old one must be silenced. An accent that betrays any foreignness, immigrants are quick to learn, will invite instances of discrimination. On the other hand, in those cases where the language is passed on, children often shun this part of their heritage due to the embarrassment of being different from their peers. Added to this, of course, is the mortification over their parents’ own ineptitude when it comes to the new language. The end result could be what linguists call First Language Attrition, that is, the process of forgetting one’s native or first tongue. In the family unit, the consequence of this amputation is a tension in the parent-child relationship, parts of both sides being incomprehensible, or better, untranslatable, to one another.

These questions seem to bubble under the surface of Jessica Gaitán Johannesson’s debut novel, How We Are Translated. The book, set to be released in the American market February of next year, centers a young couple and their “project” – as the main character has come to define the unplanned pregnancy that rocks the relationship. She is Swedish and immigrated to Scotland as an adult. He, a black Brazilian who was adopted and moved to the country as a child. The language of their intimacy is English, different from her native Swedish and his long-forgotten Portuguese. There is a question that pulsates here, then; what language will they speak to their child?

Kristin, the protagonist, does not give two thoughts to the issue. For her, deciding what to do with the pregnancy, which she seems to ignore for much of the narrative, refusing to even name it, is of more importance. The boyfriend, Ciaran, throws himself into Swedish, however. “You wanted to ‘immerse’ yourself in ‘my language’ to ‘prepare’,” Kristin tells us in a narration addressed to Ciaran, “‘For both of our sakes,’ you said, which is NOT an answer to why you’re JUST NOT HERE ANYMORE’.”

Johannesson, herself a Swedish-born daughter of a Colombian mother and a Swedish father, grew up speaking the language along with Spanish and “currently lives primarily in English,” as her author bio puts it. These biographical details raise some interesting points. First, the dedication addressed to Johannesson’s mother that opens the novel is in Spanish, showing that there is some legitimacy in Ciaran’s urgency. Second is the author’s choice of writing in her third language. In interviews, Johannesson has stated that she had been writing in Swedish for a decade before attempting to do so in English. The transition, she explains, was not without difficulty or hesitation. She still feels like a fraud. There is, she says, a sense that she should not be allowed to write in the language.

The Argentine writer Sylvia Molloy has expressed similar feelings to Johannesson about writing in English. Molloy, who was born in the Latin American country to a family of English immigrants on her father’s side and French ones on her mother’s, explores the issue of identity and language in Vivir entre lenguas(Living Between Languages). Throughout the book, the author mentions several writers who also had some sort of struggle over language. Uruguayan-French poet, Jules Supervielle, for example, believed a writer could only exist in one language and, according to Molloy, imposed the use of French in the home although his wife did not speak it. Argentine-born William Henry Hudson, another example mentioned, wrote in English, not seeing himself as one of “the natives” (as he would refer to Argentines), but is celebrated in the South American country as Guillermo Enrique, the original English novels and name erased by the Spanish-translated versions. As for Molloy herself, she states how French writer Valery Larbaud’s literary advice to “Donner un air étranger à ce qu’on écrit” [add some strangeness to what one writes] taught her to embrace what she at first saw as a weakness. The multilingualism that differentiates her prose from that of monolingual English writers should not be seen as a flaw, but as what gives her literature its vigor. Larbaud’s words, Molloy says, gave her permission “de escribir ‘en traducción’” [to write in translation].

In How We Are Translated, Johannesson seems to have arrived at the same conclusion as Molloy. Her multilingualism is what gives life to her writing. Ciaran’s obsession with learning Swedish puts the language at the center of the story, forcing it to become integral to the novel’s structure. Here, Johannesson finds room to play with language in ways monolingual writers could not. As Kristin comes to reflect on the inner workings of her native tongue, Johannesson uses translations to clue readers in to what the character is thinking. Often distributing the words on the page as if it were a poem, the author puts English and Swedish side-by-side. As such, there is a hint of a strategy of playing with the layout of the page that is often used in poetry, the space of the paper gaining relevance much like the verses themselves.

It is in Kristin’s interest in literal translations between English and Swedish that the question of language gains strength in the narrative. Ciaran’s enthusiasm about the protagonist’s native tongue breaks her automated view of Swedish. If Larbaud’s advice about literature relates to its potential to make readers see the world differently, a literary characteristic long-championed in the field as defamiliarization, Kristin’s reflections over the inner workings of language have a similar effect. A highlight of this is the discussion of how to say “sorry”:

Here are two of the ways people apologise in Swedish.

förlåt forgive

för fore

låt. let/give but also ‘song’

Then there’s:

jag är ledsen. I am sorry

but also I am sad

Ciaran opts to apologize using the second option, one that makes sense to an English speaker as the expression carries the same ambiguity as “sorry” (“I’m sorry” can also mean “I’m sad for you”, and not be an admittance of guilt). For Kristin, contrarily, the close translation between Swedish and English does not work as well. She dwells in her pain and does not forgive because she wasn’t actually asked to do so. In her head, the correct form to use to apologize here would be förlåt, leaving no room for vagueness and putting the responsibility on her to forgive. Ciaran’s lack of knowledge of such subtleties make him unaware that the friction remains unresolved. Johannesson’s use of language ambiguity works beautifully to create conflict in the scene.

Another standout example is the discussion over the word abortion. Kristin expresses how strange she finds the phrase “göra en abort“, whose literal translation to English would be “to make an abortion.” The difference from the actual translation, “to get an abortion”, seems to put the onus on the woman: she is no longer having a medical produce done, but takes on an active role. That explains the irony that pulsates in the character’s “What an activity” comment that closes the scene. There is, however, a darker undertone here that escapes Kristin (and maybe even Johannesson herself). Swedish and English are not the only languages that are at play in the novel, although they are foregrounded. The phantom of Portuguese is also present in Ciaran’s mutilated tongue. In Portuguese, the word for the Swedish abort and the English abortion is aborto. Speakers say fazer um aborto to refer to the medical procedure, whose literal translation to English would also be to make an abortion. As such, both the mother’s and the father’s native languages place emphasis on the agency of the parent. However, things take a more sullen turn when we consider the other translation for the word aborto: miscarriage. In the father’s forgotten native tongue, there is no lexical difference for two rather distinct events, the contrast being made by the adept use of the verb sofrer [to suffer] to talk about the latter.

Ciaran’s forgotten Portuguese makes another more incisive, albeit brief, appearance at the very end of the book. When the two characters finally decide to speak about the pregnancy, Ciaran abruptly asks, “‘Do you think that if our kid wanted to learn Portuguese, that it would be easier for them because of my genes?’ […] ‘I never tried’.” The question is posed out of nowhere and interrupts the flow of the conversation. The last time the language was mentioned was about 50 pages earlier. Just as quick as the question is posed, it disappears. Kristin does not answer and the couple returns to discussing how they feel about the pregnancy. The abruptness serves the narrative, however. It reveals, in a way, part of the source of Ciaran’s drive to learn Swedish. It was not simply a matter of getting closer to the protagonist, or of improving his CV as Kristin accuses him of, but also a reaction to his inability of passing on his native tongue. A form of dealing with the fact that a part of him, even if it’s a silenced one, would not be inherited by his child.

The idea of translation does not exist in the novel only in how it discusses language. The idea of cultural translation, or rather, how one is read in a country that is not his or her own, also comes into the fold. In the story, Kristin, an immigrant, works for the fictional National Museum of Immigration, located in Edinburgh Castle. The idea of the institution is to celebrate Scotland’s rich history of immigration, but there are several aspects of Johannesson’s use of the location that exposes contemporary conflicts over displaced people.

“There is no Syrian exhibition at the National Museum of Immigration,” Kristin narrates, “nor is there one, as far as I know, in the pipeline.” She continues to explain that three Pakistanis petitioned for their culture to be included, only to have their request denied “due to the need for maintenance of existing exhibitions.” These, which celebrate the Norse, the Lithuanians, the Italians, and others, are about groups who came into the country decades ago. In other words, they are peoples whose presence no longer generates discomfort for the Scottish, unlike contemporary immigrants such as the excluded Syrians and Pakistanis. There is, hence, some perverseness in the allegorical message sent by the “need for maintenance of existing exhibitions”: Scotland does not have enough room for everybody, and the new immigrants are unwelcomed. The tension over immigration continues a few lines below when Kristin states how, at the Museum, the different groups have to suggest “a very important contribution its culture made to Scotland.” That is, a group’s worth is measured by their use to Scottish society. This is not only troublesome when thinking about older migrant groups, but also contemporary ones. The latter are not taken into account in the Museum because Scotland has no use for them. They have, as far as the Scottish are concerned, no contributions to make, and are simply a hindrance to society. Much of this conversation can be related, for example, to how European countries want to apply an arbitrary criteria to decide which refugees they will allow to cross their borders: how is it exactly that we decide whose life is worth saving?

Johannesson never fully enters these heated political discussions in the book, but the moments of tension between immigrants and Scottish-born characters hint at very real social clashes. In the narrative, most of it is used to elaborate on the central conflict between Kristin and Ciaran. In its pursuit of “authenticity,” the Museum does not allow its workers to speak English. As such, Kristin, who plays the role of a Norse woman named Solveig, cannot express herself in English while working. She and her colleagues are expected to use “Translation Rooms” to reach a state of “purity.” “People’s Translation Rooms,” Kristin says, are “used for the purpose of changing into the Peoples we belong to. This is how we’re always newly arrived, always immigrants, and don’t know much of anything.” As such, the immigrant workers in the Museum quickly learn that English, as far as Scotland is concerned, does not belong to them.

For Kristin, the result of this is that speaking Swedish becomes a sort of task. She is not only not permitted to be herself at her job—here, her status as an unwanted contemporary migrant comes into play—but the Museum also makes “the first language [she] ever spoke” feel like “taking your work home with you.” Here is where Kristin’s problem with Ciaran’s learning Swedish comes in. In part, his desire to learn the language indicates a commitment to parenthood that she is not yet ready to make. But from another perspective, it represents a betrayal.

Again, the language of Kristin and Ciaran’s intimacy is English. At the moment the two first spoke, the protagonist realized “this is it, […] from now on, you are an English-speaking person. With this person, you will be an English speaker.” Thus, Ciaran’s abrupt change in how they communicate, which was never discussed with Kristin, is not inconsequential. He is not only forcing her to work at home, denying her access to English, but also shifting their relationship in ways he cannot grasp. For multilingual people, languages are not neutral and cannot simply be switched out for one another. The changes made are intentional, even if solely because expressing a certain idea in a specific language feels more right than saying it in another. As such, the language used in a relationship is personal and cannot be simply changed without causing discomfort. Ciaran’s Swedish, which had always been nonexistent between Kristin and him, breaks this rule. Therein lies part of their conflict.

In her debut novel, Johannesson brings forth discussions that have long existed (the experience of being between languages) as well as new ones (contemporary tensions over displaced people), joining the two under one specific idea: translation. In doing so, the book cannot help but also raise the question of how Johannesson herself is seen in her literary context. Is she a British author? The national model has long established the confines of how we think of literature. Somehow nationality has become the principal category used when it comes to classifying writers and literary production. However, much as the experiences of immigrants draw attention to the arbitrariness of the nation-state (why exactly should I have more right to the land I’m on than those who immigrate here? Weren’t my ancestors also immigrants?), the literary works produced by immigrants also show how limiting thinking about literature in terms of nations can be. Reading a novel like How We Are Translated shows us that maybe it is time for us to expand our imagination, not just by rethinking how we define British or any other national literature, but by making clear that categorizing Johannesson as a British or non-British author is irrelevant. The power in her writing may be precisely in how, with its plurilingualism and reflections of the immigrant experience, it has the potential to reject such restrictive labels. It will be interesting to see if the author continues to resist such labels in her future work.

Allysson Casais is a PhD student in Comparative Literature at Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brazil.

This post may contain affiliate links.