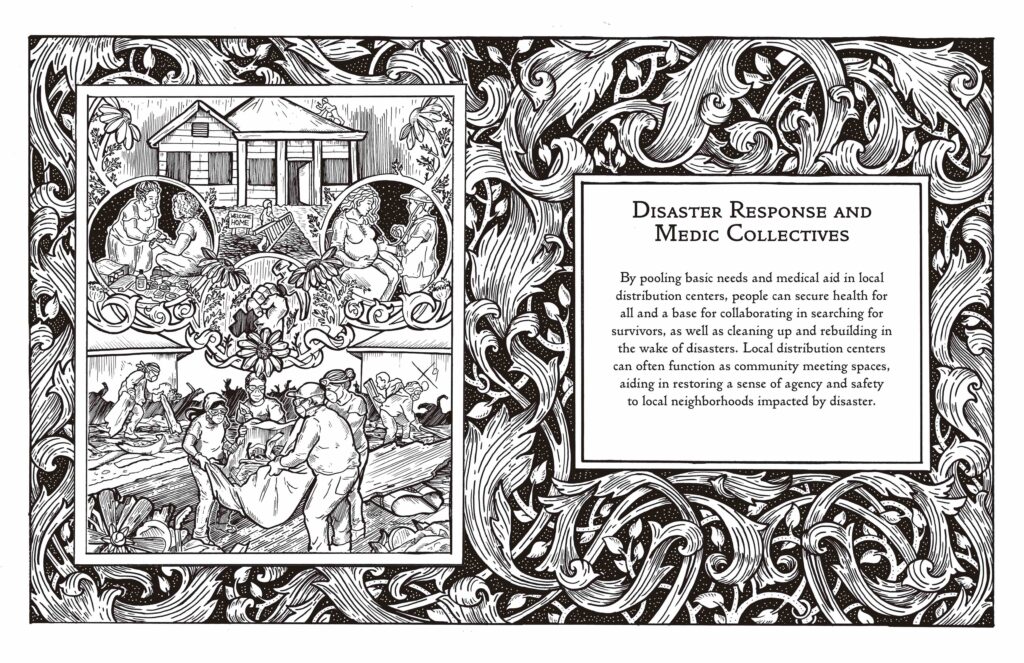

The first thing I noticed when the COVID-19 pandemic hit its full stride in the spring of 2020 was not just the looming political and economic crisis, it was how quickly people in my neighborhood began to reach out. Facebook Groups, chat threads, door knocking, and a range of types of outreach became commonplace as people turned towards one another, looking for a way to survive the panic through cooperation. “Mutual aid,” this idea that we can create a mutually beneficial system of care, became a common sense solution to a pandemic that companies and governments were unable, or unwilling, to give us the resources to endure. Groups popped up around in cities and towns around the world, using social media and communication technologies to coordinate food deliveries and medical care, hands on support and transportation. Mutual aid became the operative concept that launched us into the abolitionist protests of 2020 or the encroaching wildfires that devastated the West Coast.

Mutual aid is not a new concept. Instead, it has been foundational to radical, anarchist political movements that see it as an alternative to the hierarchical models of resources distribution that capitalist individualism is built on. Groups like the Black Panthers had “survival pending revolution” programs, offering medical care and free breakfast, and Food Not Bombs provided free food to both communities in need and to support ongoing protests. This care work was political: by coming together, using direct action to solve a human need, we see the possibility of a new way of life. Even if for just a moment.

The idea has deep roots, and was written about back in the 19th Century by early anarchist theorist Peter Kropotkin. His now classic essay “Mutual Aid” looks at the ways that both animal and human societies grow and evolve not just in competition with one another, but by cooperating, whereby everyone benefits by collaboration. His book was an alternative history to the encroaching Social Darwinism and pathological selfishness that many of the loudest scientific voices were offering, and the text has become a hallmark for anarchist movements trying to offer a different vision of human history and futures.

PM Press recently created a new edition of Mutual Aid with introductions by David Graeber, Andrej Grubačić, and Ruth Kinna and graced with art by the graffiti artist N.o. Bonzo, who does creative interludes and frames each page with drawn images of both historical and contemporary acts of mutual aid. Their work opens up the vision of what mutual aid can be to include a huge range of things, from childcare collectives to community farms to labor solidarity, and this helps to bridge the historical time that Kropotkin is writing in and today’s response to global health, economic, and ecological crises.

I spoke with N.o. Bonzo about their work, the impact of Kropotkin’s book, and what mutual aid can mean for diverting our society’s path and, potentially, charting an entirely new one.

Shane Burley: How did you first encounter the book Mutual Aid? What struck you about it?

N.o. Bonzo: I came to this book pretty early on.

I was struggling with this idea, which a lot of us struggle with, that there are any fixed and fundamental things you can say about human nature. For example, people are “fundamentally good,” or “people are fundamentally bad,” or “people will fuck each other over.” When I was younger I absorbed a lot of the dominant narratives that lend more to the latter of those examples. That was in addition to seeing the way the world was arranged as something fixed and inevitable.

And so finding Kropotkin’s book Mutual Aid, which is just a very simple and lovely articulation pushing back on all the above, just felt like it opened up a million possibilities. Those possibilities were that human nature is not fixed, that it is an endless web of choices and a variety of tendencies, that cooperation and a sense of shared responsibility to each other are not only potentials for action but desirable ones, and that we could shape the world in any number of ways (and have done so), was just captivating to me.

I think that is the way a lot of these simple anarchist texts grab a lot of people. There is a sense of a weight being lifted from your shoulders and that things don’t have to be the way they are. You don’t have to fuck people over to survive.

How did this book come together? How did you approach doing the art on such a massive project?

I was incredibly fortunate that PM Press and the other contributors were so stoked about the idea. Having others excited about the projects you’re pursuing makes them more enjoyable to engage with and even lends to the excitement of showing them what you’re up to.

As far as the art, I have no clue and I look back now and can’t believe I pulled it off.

I drew heavily from our shared history of liberatory art and relied heavily on the visual language present within the works of the Arts and Crafts movement who had relationships with Kropotkin at the time. Working within a tradition that’s been established before you is a million times easier than trying to create something whole cloth. I think this project kinda helped me to develop in my own practice since it was the first time I’ve really done anything with this type of scope. I have found myself to be inking and designing way faster now which feels like a great accomplishment.

What is mutual aid? How is it different from charity?

Mutual aid is actually this really impossibly simple concept. It’s just a choice to assist other people or to cooperate instead of destructively seeking personal advantage. It can sometimes involve personal sacrifice or risk, but it’s something that happens between equals, rather than from the top down, and it is about offering support and collaboration rather than imposing something you think is better. Charity, by contrast, is something that happens top down, usually in a rather patronizing way, and it doesn’t have the possibility of nurturing an egalitarian relationship. Mutual aid can be, say, a graffiti artist tagging “this pole won’t support your weight” to warn someone of structural danger, or someone jumping in a river as someone struggles against drowning.

Charity is a social worker deciding to provide you with food stamps after you spend hours in the office prostrating yourself.

And mutual aid is also happening everywhere. From graffiti writers, people who wanna throw an illegal music show, people in prisons, to even cops or dictators. So much of how we actually articulate mutual aid today includes other anarchist principles such as solidarity or a rejection of social relationships that reinforce hierarchies.

Charity, as a top down institution, is a moment of exchange in which no relationship, no connection, nothing really grows or develops from it. Generally, a single moment of intervention into the outcomes of things like capitalism, white supremacy, transphobia, etc., while doing nothing to challenge or potentially change the underlying social conditions. It’s funny, if you look back on old anarchist publications at the time you actually find numerous scathing loathsome critiques of charity.

That’s not to say that I’m not completely stoked when a friend gets a housing voucher and now gets an apartment for the rest of their lives. That’s way cool. But also it’d be even cooler if all of us took over a condo, challenged peoples’ property claims to it, and then there was free housing outside of any state or institutional purview. That’s also an infectious act that can inspire others, whereas charity is generally not exactly the most easily replicable thing since generally folks need access to some form of capital to perform it. Whereas me and some buddies can get some bolt cutters and get a condo opened up real quick, though the state, judges, and cops will probably intervene to disrupt this mutual aid tendency in action.

Have you ever done any mutual aid work? How did it affect your life?

Exhaustingly, and pleasantly, yes.

Though, of course, like our own lives are composed of endless examples of this tendency outside of more formalized group formations.

For me personally, I found it increased my feeling of agency and the potential to challenge the absolute overwhelming structures built up in the world today. Reaffirming commitments with each other to each other is definitely something that has nothing but a positive impact on my life. I think about a lot of work exploring the impacts of trauma. And a reoccurring theme in the support of folks experiencing PTSD is one of being able to make safe connections to others as a fundamentally healing act. Which is also interesting as we can see that people who experience traumatic events report that feelings of camaraderieship and fraternity during the event lessened the traumatic impact and also led to a decrease in developing PTSD.

These bonds and commitments can really give you a sense of deep and enduring hope that we have the potential to make a life really worth living.

Mutual aid groups have grown so much over the past few years, why do you think that is? What role do these groups play in our future?

One of the lines that just runs in my mind endlessly from the book is that mutual aid is a tendency that has so remote an origin it could not be traced. In the same way you could have someone who sees someone fall and thinks “I’m gonna kick ‘em,” you have another person who without thought rushes over to help them stand back up.

At the beginning of the COVID crisis you had individuals and groups spontaneously organizing to provide support to each other on an incredible scale. And then folks were like “oh hey, that’s this mutual aid thing.”

I think the tendency just displayed itself on such a scale where folks couldn’t help but make the observation, even though our lives pre-covid had any number of daily occurrences of this tendency.

We are facing any number of crises that are immediate, and the government is not going to “save us.” They are more than likely going to just expand policing, strengthen borders, and perform any number of actions which are just violent articulations of white supremacy, transphobia, classism, ableism, etc.. I think it’s probably safe to make that guess at least.

And so as these crises continue to unfold, we are the only ones each other have. And these groups can contain the seeds of the potential to radically reimagine the way we are in relationship to each other. When mixed with other anarchist principles that folks include with mutual aid work, such as solidarity and a rejection of hierarchy, they have quite a bit of potential for us to meet these crises in a way where we can experience a radical transformation.

How does Kropotkin’s vision of mutual aid challenge our culture’s individualist, capitalist ethos?

Oh golly, how does it not? Kropotkin’s text is so much more than a scientific work seeking to challenge Scientific Darwinism. It’s also the beginning of what he saw as his exploration of what an anarchist morality would be. I really strongly advise folks to read the introductions from David Graeber, Andrej Grubačić, and Ruth Kinna who explore this intervention more broadly and directly.

When we look at what he was responding to, it was the conclusions that Huxley and others were drawing from Darwin’s work. Huxley has this goofy essay that claims that human and non-human animal history and nature is just tooth-and-claw a battle against all for all, but another element of his piece is he’s like, the only thing we can do to not devolve into our “natural human condition of violence/struggle/etc.,e tc.” is to have a super awesome powerful state. These types of conclusions are mostly referred to as Social Darwinism today and used to justify and uphold any number of violent institutions like the state, capitalism, white supremacy. And those conclusions are still playing out now. I think everyone has seen some of the horrifying eugenicist responses we have seen recently to COVID mortality rates or been increasingly exposed to fascist rhetoric which pulls upon Social Darwinist conclusions as well.

So this articulation of the breadth of cooperation that can be found in human and nonhuman animals is a direct push back to those ideas. In addition to Kropotkin’s conclusions that this cooperative tendency led to greater outcomes of health, safety, quality of life, he also concludes that the state, capitalism, selfishness, and the like, are the things that most disrupt these mutual aid tendencies and lead to a higher degree of suffering and violence.

If having power over people, if accumulating eight bajillion dollars, if putting people in prisons are all the natural outcome of following a theory that believes that competition is natural and morally just, then a book exhaustingly detailing how absurd that proposition is is definitely an attack on the inevitability of the world we have now.

What lessons do you wish mutual aid organizers would learn from this book?

I think the biggest lesson is that the examples of mutual aid are so far and so broad, and exist not just between humans but between all living things.

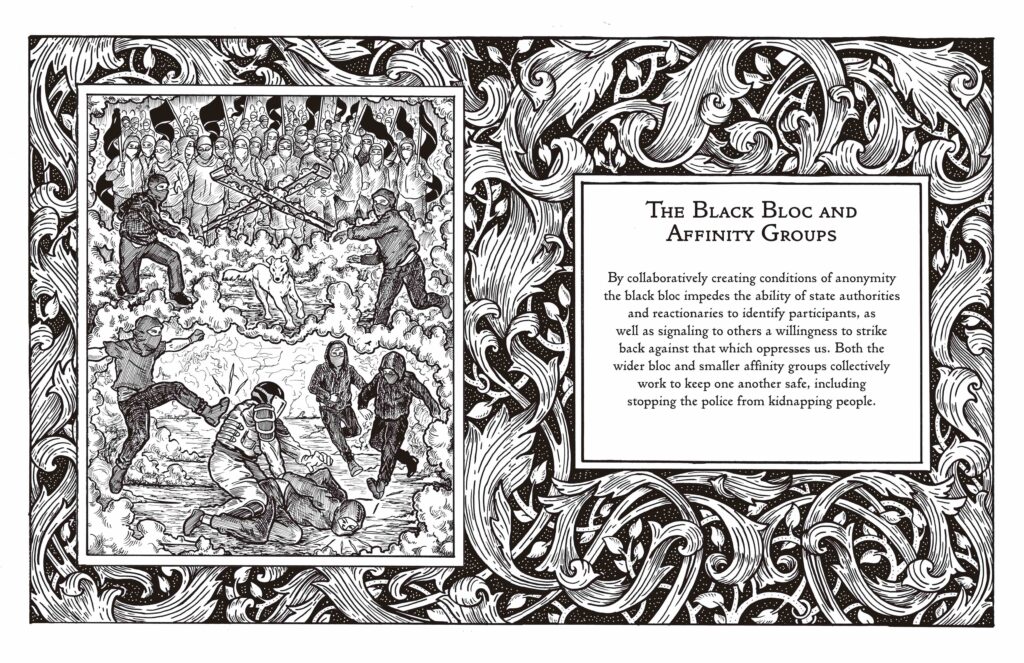

To Kropotkin, mutual aid was not just some huggy-wubby thing defanged of its radical potential for attack and defense. In the book Kropotkin articulates numerous examples from peasants greeting some reagent now claiming lordship over them holding swords, or striking workers confronting the bosses. Bear in mind that Kropotkin came from a time when workers didn’t just vote to go on strike, they engaged in fierce defense against the people who directed a lot of the violence in their lives. Kropotkin was a supporter of propaganda of the deed, the idea of taking action as a way of inspiring people to take further action themselves. So you have anarchists and revolutionaries taking incredible brave risks, often losing their lives to guillotines or firing squads, to assassinate tyrants, kings, and industry barons. You have sabotage, anarchists blowing up whole shipping freights after bosses hired fascists for scabs or throwing those good old shoes and wrenches in the works.

That doesn’t mean you’re not doing mutual aid if you’re not trying to kill a reagant, but that conceptualizations of mutual aid should not be reduced to just ensuring people have access to their survival needs.

What advice do you have for people starting mutual aid groups themselves?

Take care of yourselves. Don’t martyr yourselves.

When you move into a space of reciprocity and connection with people you are impacted by their experiences as well, which can include violence. You start to build up more and more anger and maybe frustration as you recognize all the careful constructions the state has built up to harm people. Compassion fatigue, burnout, vicarious trauma are all real. Sharing egalitarian and caring relationships with others can be one of the strongest ways to address these emotional and mental needs that arise.

So prioritizing the types of relationships of care and reciprocity that you hope to achieve in the work of the group with each other and yourself are important.

In addition, it can’t just be mutual aid. It has to be a combination of other principles coming into alignment with your values and actions. The tendency to call something a “mutual aid group” is actually quite a new phenomenon. Generally, you would have more projects that merely described mutual aid as one of their core values. And so though the tendency has powerful and transformative potential, it does need to be coupled with other principles as well.

What role does radical writing and art like this play in building up a social movement?

We absolutely have to have it. What else is it other than a potential signpost for the world we want to achieve. People often claim that the media is “value neutral,” which is bizarre to me. How can you be value neutral?

Media exists as a place of exploration and celebration for the values and ideals we hold within our social movements. As an anarchist, I find that when you talk to people about how they were drawn to anarchism they often identify subcultural spaces like punk or hip-hop as early influences. Spaces are incredibly rich and saturated with expression, most of which is not really going to be identified as art necessarily or end up in a conventional gallery or museum.

The art that’s present within those spaces comprises an element of the shared community’s values and aesthetic, which exist in the day to day experience and practice of its participants.

When I think of political art, I think more of what are the things being painted on punk houses walls, what are the stick and poke tattoos, what are the tags scrawled outside by graffiti artists, what are people wheatpasting, and the common shared refrains across a number of songs we sing? What are those things that daily reaffirm a commitment to a certain set of values and create a sense of a shared project, which hopefully is also resulting in liberatory activity and exploration.

Our art is both a signpost for ourselves and others, often the only way we really find each other. It’s essential.

Shane Burley is the author of Fascism Today: What It Is and How to End It (AK Press, 2017), and the recently published Why We Fight: Essays on Fascism, Resistance, and Surviving the Apocalypse (AK Press, 2021). His work has appeared in Jacobin, Salon, Truthout, In These Times, Waging Nonviolence, ThinkProgress, Political Research Associates, Alternet, and Roar Magazine.

This post may contain affiliate links.