This essay was first made available last month, exclusively for our Patreon supporters. If you want to support Full Stop’s original literary criticism, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter.

Begin with I. I write the first sentence.

Each typed letter initiates a site-specific temporality, a here and a now. To begin to think about Gertrude Stein, we begin with beginnings. Begin with a new relationship to order, one which moves to dismantle semantic codes and complicates syntax. To engage with Stein’s language experiments is to move against hegemonic systems of discourse and interrogate subsumed forms, to engender a more diverse compositional sensibility.

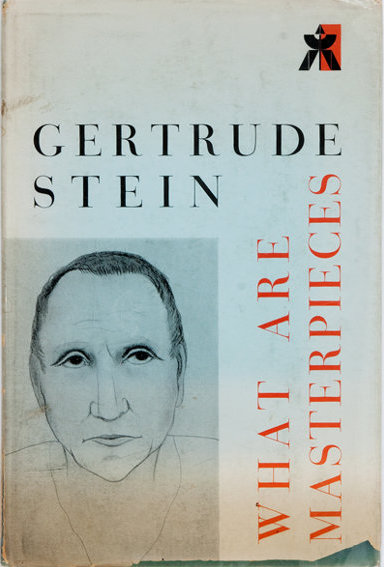

This is another beginning: Perhaps this is the first sentence. Perhaps before typing it I searched my shelves for the red-faded-pink cover of Gertrude Stein’s 1926 book What Are Masterpieces? The book flips open, a piece of paper drifts to the floor–once a makeshift bookmark. I fumble through pages, find the text “Composition as Explanation.”

First delivered as a lecture at Cambridge (where I am currently living) and Oxford, Stein’s “explanation” both mystifies and demystifies her writing process.

“There is singularly nothing that makes a difference a difference in beginning and in the middle and in ending except that each generation has something different at which they are all looking. By this I mean so simply that anybody knows it that composition is the difference which makes each and all of them then different from other generations and this is what makes everything different otherwise they are all alike and everybody knows it because everybody says it.”

Rather than explain, Stein uses language to illustrate her point. It becomes a demonstration in which similarity and difference coexist and comingle; an ambiguity is presented as certainty; logic dissolves. We can see here a trace of modernist values later echoed in Ezra Pound’s slogan “make it new.” Difference is the base from which a newness can emerge.

Before committing to poetry, Stein studied medicine at Johns Hopkins University, where she transferred the tradition of experiment she learned from the sciences to the field of language. Her first piece of published writing (another beginning) was a text in the 1898 issue of Psychological Review titled “Cultivated Motor Automatism: A Study of Character in its Relation to Attention.” It is a report that describes the experiments she performed to investigate automatic writing. She records her steps in detail, how she “suspended from a high ceiling a board just large enough to support the forearm, the hand hanging over and holding a pencil” and methodically documents her findings: “Type I, Case I … The subject is irritable, and feels a distinct shock when her pencil slips from the paper.” Even in her earliest experiments with language, she was already interested in new ways of interacting with language, rhythm, and process.

I start with my forearm on a pile of books and set a timer for ten minutes. My lines shiver, my sketching fatigues, I feel a distinct shock when my pencil slips from the paper. I pick it up and again begin: “Composition as Explanation” doesn’t follow the rigorous methodology of a scientific experiment, but it does offer some insight into Stein’s process. The three concepts which are essential to the piece (ones which she was already exploring in her experiments in automatic writing) are:

I. composition

I. temporality

I. nature

Through her engagement with these concepts, Stein develops a theory of contemporary, or con-temporary, literature that allows for a reframing: a process which performs what it theorizes, one that assumes the conditions of a continuous present, using everything and beginning again.

“I began doing natural phenomena what I call natural phenomena and natural phenomena naturally everything being alike natural phenomena are making things be naturally simply different…”

I. Nature

There is a simplicity in acknowledging an implicit diversity in the natural world: No two things are heterogeneous, no two atoms alike. And so it goes with composition. Natural phenomena are acts of perception. “Doing natural phenomena” means seeing outside of categories, liberated from any impulse to classify or sort or cull. Here is where Stein encourages a use of everything– every minute, mundane detail, every expression of difference, is incorporated into the whole. In Stein’s thinking, everything is useful in the production of literature, everything is relevant to the act of perceiving, every thing is different, every thing is interrelated and can be combined. The simple nature of difference is an addition of smaller diverse components. As Deleuze writes in his book The Logic of Sense: “Nature is not attributive but rather conjunctive: it expresses itself through ‘and,’ and not through ‘is.’ This and that—alternations and entwinings, resemblances and differences, attractions and distractions, nuance and abruptness.” We see this same thought weave through Stein’s work. It leads us to understand that to form a whole unit—a composition—it is necessary to acknowledge the essential nature and coexistence of these alterations and how they manifest when placed together.

I move from couch to countertop, my perception of the room alters, I notice its difference, I begin to write this thirty-second sentence. More than recognizing difference what Stein suggests is beginning from an acknowledgment of diversification in nature. Stein writes: “I find that I naturally kept simply different as an intention.” This became a generative concept in her work, to write from a place of inherent diversification. To recognize that all things are naturally different allows one to approach language as if nothing is the same. It decenters the human and allows a formation where no one rhetorical structure will ever be identical to another. Form becomes naturally diverse, and to accept that is to embrace the experimental.

I. (re)Peat

Within the word composition, we find “composit,” and if we reach further, “compost.” With a mistrust of etymology but a penchant for association, I write: The three words (composition, composit, and compost) stem from the Latin componere, from com “with, together” and ponere “to place.” When we think about the composition of a flower arrangement, we may be thinking about the act and process of assembly, but we may also be thinking about the parts. Is it composed of roses or carnations and how many and what color? When we compost, we are also de-composing. To combine organic substances together, they must first be broken down into much simpler matter.

“Everything is the same except composition and as the composition is different and always going to be different everything is not the same. Everything is not the same as the time when of the composition and the time in the composition is different. The composition is different, that is certain.”

Stein plays with form, breaking and re-compos(e)(t)ing clauses and sentence structures. The form of a composition recombines, shifts to emerge anew within its own historical time frame and within the time of the composition itself. Her own language and form, mirroring the content.

Writing in the 20s, Stein was deeply influenced by the developments of Cubism and Dada, her experiments in automatic writing and formal play maybe even a precursor to Surrealist techniques. The geometric shapes rendered by her artist friends enacted an altering of perception, blurring depth and flatness, abstracting representation. Stein posits that the subjective perspective and situated perception accounts for a difference in composition. The movement of Cubism sought to break away from the realistic tradition of western art and depicted subjects from many different angles, creating a fractured style of composition. The subjects didn’t change, just the way in which they were perceived. Moving in this milieu—hosting her famous weekly salons where the artists would gather—Stein approached her compositions with a similar altered perspective:

“The only thing that is different from one time to another is what is seen and what is seen depends upon how everybody is doing everything. This makes the thing we are looking at very different and what those describe it make of it, it makes a composition, it confuses, it shows, it is, it looks, it likes it as it is, and this makes what is seen as it is seen.”

Here she acknowledges that the form of perceiving diversifies and impacts the making, or poesis, of a composition. From one generation to the next, our approaches to perception embed themselves in our thinking, finding natural expression in the architectures of our compositions.

Meanwhile, in my garden: The earthworm makes its way through the compost. As it burrows through the soil, it aerates the material to improve the quality. With no eyes or ears, the only thing that alters its perception are the receptors that allow it to know if it is above or below ground, yet through this act of perception it moves and reforms the composition of the matter around it.

I. Con(tempo)rary (beginning time of composition: 11.23am April 15, 2021)

Diversification is not the only natural phenomena Stein addresses. She writes that: “The time when and the time of and the time in that composition is the natural phenomena of that composition and of that perhaps every one can be certain.” Stein’s theory of composition is deeply concerned with time. It offers an approach to writing from within the present with a technique of regeneration and repetition/returns.

To reach her theory, Stein assumes that the movement of time involves a continuous present—a grammatical fiction generated out of her literary prose—and beginnings. But she differentiates between the two: “Continuous present is one thing and beginning again and again is another thing. These are both things.” You begin again and again and again while in a continuous present. The present is a continuous plane of ongoingness. The term could serve to unify a person living at the same time as another (which prompts certain movements like Cubism to emerge) or could perhaps serve as an apt way to describe the “contemporary” in that it is only such that it is in the present moment.

Beginning again and again requires a gesture of reiteration, a practice of recursive writing and living. Again and again and again, beginning is a reiteration. Marjorie Perloff writes: “It is not the appearance of a word that matters but the manner of its reappearance.” Each time a word reappears it emerges new. Placed next to something different, a word takes on a different coloring. Referencing her process of writing the portraits in The Making of Americans, Stein writes:

“So then naturally it was natural that one thing an enormously long thing was not everything an enormously short thing was also not everything nor was it all of it a continuous present thing nor was it always and always beginning again. Naturally I would then begin again. I would begin again I would naturally begin.”

There is a slight alteration in the coloring of “naturally” at the beginning of the second to last sentence—as if the word “obviously” could just as likely replace it—compared to the “naturally” at the end of the quote which implies a sense of ease to the process. Stein’s grammatical structure is a process which functions with/among the continuous present but also continuously begins again, not as a straight line but rather an ellipse—one that loops back in its recurrence but moves forward in its meaning-making.

Stein’s process moves in a way that creates an artifice of ambiguity and forms a structure that can reconfigure infinitely. There is a disruptive function to her use of repetition, a disorienting pulse. As Lisa Robertson writes: “The repeatedly beginning time of composition is revolutionary time.” The act of beginning stays contemporary and changing, it exists within a continual present, accepts the nature of diversity, stands outside of linear time and refuses classification. It is revolutionary in functioning outside of the normal structures. Beginning again and again disregards formal constraints, it removes itself from what has come before it while still remaining in dialogue with it, it shakes off its associations and stands alone in its inherent diversity. A continuous present is not timeless—we are always in dialogue with our histories, we carry our lineages within words—but it does reconfigure these histories and approach them anew.

It is also not only time which is revolutionary. Stein posits that writers are categorized as outlaws until they are classic. “Those who are creating the modern composition authentically are naturally only of importance when they are dead because by that time the modern composition having become past is classified and the description of it is classical.” This could perhaps also serve in our definition of the contemporary as something which isn’t classified or truly recognized until enough time has passed to classify it. Thus, to be contemporary is to renounce classification and, in some ways, a certain level of eminence.

Addendum 1: Re(f)use

“There is almost not an interval,” Stein writes toward the beginning of “Composition.” This sentence, itself an interval, stands alone as a landing place between two longer paragraphs. Its aphoristic quality invites the reader to pause and turn it over: There is an interval, but it is almost not there. The sentence also carries a refusal to conform to linear time: The quality of near nonexistence allows us to enter an imaginative realm suspended, a time outside of time. Stein’s continuous present is a kind of improvisation which refuses to be held by pre-existing commitments—or to commit, if it were possible, to the ambiguity of the present. What is initially a critical fiction can also become a powerful procedure, one which might lead us to ask what it would mean to break out of the language of the present insofar as it is pre-scripted. This liminal time-space is capacious and generative. It liberates thought.

William Carlos Williams writes that Stein is concerned with writing “but in such a way as to be writing envisioned as the first concern of the moment, dragging behind it a dead weight of logical burdens, among them a dead criticism which broken through might be a gap by which endless other enterprises of the understanding should issue— for refreshment.” Here Williams expresses the need to rupture criticism in order to create a gap from which a new thinking can emerge, and signals Stein’s writing as a promising step in that direction—something that could offer a rupture. What if we could break through criticism with multiple ruptures and multiple gaps? How much more “endless,” then, would be our “other enterprises of the understanding”?

In revisiting and returning to Stein’s thinking, we can consider a way to enact this rupturing. This call to open up textual paths will be further echoed in the project of Language Poetry, and we see it specifically appear in Lyn Hejinian’s “The Rejection of Closure.” It is important for us to now revisit these texts, to remain in dialogue with them. While critical literary production seems to be moving towards standardized formatting and jargon, there is a need to decenter our subsumed forms, to break them apart and create more complicated ways of textual critical practices. With more and more interest in the intersection of creative and critical writing, there is an invitation to play at the threshold, one which Stein would have encouraged.

Addendum 1: Begin

1. Seldom incorporated into the anthologies of theory and criticism, Stein’s rhetorical provocations carry within them a naturally important critical force, a powerful heuristic through which to think through contemporary experiments in criticism. Out from under the “dead weight of logical burdens” Stein configures a new type of critical language (Williams 113-120).

1. A fractured, hybridized mode of criticism can create something more multivalent which can offer different points of access and cater to non-normative styles of engagement. While a text with no familiar road map can be intimidating, those striven to dig like worms through the compost can create paths to breathe new life into the text and generate potential for recursively altered experimental readings.

1. Bakhtin defines hybridization as “a mixture of two social languages within the limits of a single utterance, an encounter, within the arena of utterance, between two different linguistic consciousness, separated from one another by an epoch, by social differentiation or by some other factor.” This echoes the dialogue with history enacted by language, and the differentiation in acts of perceiving Stein alludes to. Maybe the hybridized work is one she was gesturing towards.

1. I’ve lost sight of the earthworm but I sense it digging through this text, its thin tunnels separating while simultaneously blurring the material.

1. Again and again and again.

1. By piercing our critical thinking with intervals, gaps and beginnings, and engendering poetics with more complicated epistemologies, we can open up our “enterprises of understanding” and juxtapose the pieces in different orders.

1. We can refuse the forms institutionally imposed upon academic writing; we can refuse to conform; we can refuse category.

Further Beginnings:

Bakhtin, M. M., Pam Morris, V. N. Voloshinov, and P. N. Medvedev, The Bakhtin Reader: Selected Writings of Bakhtin, Medvedev, and Voloshinov, E. Arnold, 1994

Deleuze, Giles. “Lucretius and the Simulacrum” from The Logic of Sense, 1969. Revolution: a Reader, by Lisa Robertson and Matthew Stadler, Paraguay Press, 2012, pp. 133-47.

Doolittle, Hilda. “Notes on Thought and Vision”, Notes on Thoughts and Vision & The Wise Sappho, City Lights books, 1982, pp. 17-57.

Perloff, Marjorie. “Poetry as Word System” The Poetics of Indeterminancy. Northwestern University Press, 1999.

Retallack, Joan. The Poethical Wager. University of California Press, 2003.

Stein, Gertrude. “Cultivated Motor Automatism: A Study of Character in its Relation to Attention”. Psychological Review, 1898, pp. 295-306.

Stein, Gertrude. “Composition as Explanation” from What are Masterpieces? 1926. Revolution: a Reader, by Lisa Robertson and Matthew Stadler, Paraguay Press, 2012, pp. 133-47.

Williams, William Carlos. “The Work of Gertrude Stein”. Selected Essays of William Carlos Williams. New Directions, 1969, pp. 113-120

Emma Gomis is a Catalan American essayist, poet, editor and translator. She is the cofounder of Manifold Press. Her texts have been published in Denver Quarterly, The Brooklyn Rail, Entropy, Asymptote, and Vice Magazine among others and her chapbook Canxona is forthcoming from b l u s h lit. She was selected by Patricia Spears Jones as The Poetry Project’s 2020 Brannan Poetry Prize winner. She holds an M.F.A. in Creative Writing & Poetics from Naropa’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, where she was also the Anne Waldman Fellowship recipient and is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in criticism and culture at the University of Cambridge.

This post may contain affiliate links.