[New Directions; 2023]

Tr. from the Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa and Patricio Ferrari

Álvaro de Campos is a poet of great contrasts. Many of his poems, particularly the earlier ones, sing with the excitement of life, proclaiming the poet’s strongest, most urgent desire: “[t]o feel everything in every way.” These poems truly buzz; they might even overwhelm. Later, Campos’s poetic voice becomes melancholy, despondent. When he laments the disappointments and the drudgery of life, we wonder that these poems come from the same previously exuberant man. He wavers, too, between nostalgia and a Futurist obsession with machines, between the metaphysical and the concrete, the mystical and the banal. He is cheeky and, quite possibly, sincere; playful and somber. In short, Campos is always changing directions, always putting on new versions of himself in his poems, as if adjusting the monocle he is said to wear, an inclination shown in his collected works.

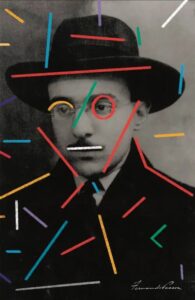

Translated into English by Margaret Jull Costa and Patricio Ferrari, the present book collects all the poetry and prose of Álvaro de Campos, a kind of literary persona created by the modernist Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa. Called “heteronyms,” Campos and the dozens of other such personae are far from fictional authors, since Pessoa conceived of each heteronym as being distinctly himself, even if their styles, worldviews, and biographies diverge widely from those of the others.

Campos was a naval engineer born in Portugal in 1890 and educated in Scotland and who sailed the world before settling back in Portugal. His background explains why many of the earlier poems in the collection feature maritime scenes or themes of travel, and why some poems include technical diction borrowed from Campos’s daytime engineering job. None of this background about Campos’s biography or the other heteronyms is truly required to enjoy Campos’s poems, however, and a biographical note and an introduction provide succinct context anyway. The poems can thus be read on their own or alongside the number of Pessoa translations and a biography published in recent years.

Some of the prose pieces, on the other hand, may be less interesting to a new reader of Pessoa. A series of short texts, for instance, informs us of how Campos came to meet his poetic master and another of the main heteronyms, Alberto Caeiro. These texts describe the profound influence Caeiro had on Campos the budding poet: He once suffered a “mental earthquake” during a conversation with Caeiro, whose words later “collided” with Campos’s soul, to list just two examples. The conversations themselves reveal much about the heteronyms and their differences. After Campos recites lines from a Wordsworth poem about a yellow primrose, Caeiro, who always sees things just as they are, simply laughs and says, “That simpleton had a good eye: a yellow flower really is only that, a yellow flower.” These pieces read as a delightful companion to anyone already familiar with the heteronyms, or who has previously read The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro, which Jull Costa and Ferrari also translated. But while the interactions between the heteronyms are often charming and funny, they may not be meaningful to a new reader of Pessoa. Newcomers may be better served by Fernando Pessoa: Selected Poems, translated by Richard Zenith, which collects poetry from the three main heteronyms and from Pessoa himself. That book provides a more compact overview of the heteronyms and their poetry, whereas The Complete Works of Álvaro de Campos can seem rambling and baggy at times, at 350 pages. And anyone interested in Pessoa’s prose should of course begin with his masterwork, The Book of Disquiet, also available in a Jull Costa translation.

Nevertheless, Campos’s poems are very much worth reading. They often examine a feeling or a sensation drawn from a commonplace, even banal experience—reading a book as a child, sitting in an office, traveling—or a more unusual one, like being beaten and tortured by pirates. Sometimes they turn on themselves to interrogate sensation itself. Indeed, the concept of “sensation” may be more important in these poems than any particular sensation. Put differently, if other poets feel, Campos thinks about feeling, or even thinks about thinking about feeling. In one late poem, for instance, Campos describes sitting aside a quay and watching people arrive at his city:

I carry with me the great weariness of being so many things.

The first latecomers are arriving,

And suddenly I grow impatient with waiting, with existing, with being,

I leave so abruptly that the porter notices and stares at me, but only briefly.

I return to the city as if to freedom.

It’s worthwhile feeling even if only then to stop feeling.

As in so many of Campos’s poems, the mundane drifts into the metaphysical. Simply being is rarely enough for Campos; he needs to think intensely about being, and feeling, and everything else.

Campos’s thinking—even his overthinking—creates what at first might seem to be a tension throughout many of the poems: Campos wants to feel everything, but at the same time he thinks everything. When he describes sitting in a café, sailing down the Suez Canal, or any other experience, he pulls back from his physical sensations at their most vibrant to dissect them, so that his poems, even if they are rooted in sensation, can seem cerebral or abstract. Yet this is all part of Campos’s project. By closely examining his own sensations, Campos becomes a real poet. “The superior poet,” he writes in one prose piece, “says what he actually feels. The average poet says what he decides to feel. The inferior poet says what he decides he should feel.” Campos must discard the false sensations borrowed from books and other people; he has to open himself to the world as he feels it. This makes his poems, which can sometimes read like dialogues where the only participants are Campos himself, intensely personal—so much so that we forget at times that Campos, properly speaking, never existed.

His examination of concepts and sensations often leads to paradox, one of his primary poetic devices. Lines such as “The more useful the more useless— / And the truer the more false—” appear throughout many of the poems. This makes sense: We’re dealing with a poet for whom nothing means what it seems to mean at first, and whose feelings often aren’t the feelings he first thinks they are. His way of turning everything on its head also means that his poems sometimes contradict one another. The later, more cynical poems include lines expressing his despair: “How repugnant life is!” and “To hell with the whole of humanity!” These lines sound very little like the buoyant, almost mystical lines expressing the speaker’s sympathy with everyone and everything: “But I myself am the Universe.” The contradictions aren’t too surprising though, not only because the poems in his collected works were written across a span of decades, but also because Campos never seems interested in creating a unified, coherent system about being and feeling. When he writes about the gods and declares that he has “different beliefs every day,” we don’t doubt him. His poetry, then, can be truly exciting and unexpected, an intellectual adventure mirroring the unpredictability of Campos’s worldly ones.

This is all a testament, of course, both to Pessoa’s and his translators’ skill. In particular, the translators have managed to make the rhythm of the lines always sound just right in English. Campos’s diction, clear and seemingly unadorned, comes across well in translation too. The present book doesn’t include the Portuguese originals, but we always feel them, even as the translations stand firmly on their own. And given the sheer number of poems, and the sense that some of them were never finished, their translation is truly impressive.

In the end, Campos is a poet, not a philosopher, and it shows in his poems, which are often truly beautiful. They work not just because Campos thinks about feeling but because he manages, in verse alone, to make us feel what he feels, to believe him, as in these weary lines:

I’ve traveled through more lands than those I set foot in . . .

I’ve seen more landscapes than those I laid eyes on . . .

I’ve experienced more sensations than all the sensations I’ve felt,

Because however much I felt, I always wanted to feel more,

And life always frustrated me, was always too little, and I unhappy.

And despite his more intellectual themes, Campos doesn’t take himself too seriously. His poems can be audacious, wild, and even funny, occasionally bordering on parody. The collection includes poems about ridiculous love letters and sonnets about writing sonnets. One poem, addressed to an imaginary lover named Margarida, ends with a note informing us that it was written “by the Naval Engineer Senhor Álvaro de Campos in a state of alcoholic unconsciousness.” Even the melancholy poems sometimes seem so pathetic as to border on the ridiculous. In one poem, for instance, the speaker says that he is “as alone in the world as a broken brick,” a maudlin image that can only be read with a knowing half-smile.

Noah Slaughter writes essays and fiction, translates from German, and works in scholarly publishing. He lives in St. Louis.

This post may contain affiliate links.