[Agate Publishing; 2021]

“Yet, with all my being, I refuse to accept this amputation. I feel my soul as vast as the world, truly a soul as deep as the deepest of rivers; my chest has the power to expand to infinity. I was made to give and they prescribe for me the humility of the cripple.” Frantz Fanon wrote this in 1952, towards the end of chapter five of Black Skin, White Masks, “The Lived Experience of the Black Man.” There, he explores colonialism, racism, and among other things discusses the way language shapes the relation between black and white, the colonizer and the colonized, the oppressor and the oppressed. To “grasp the morphology of this or that language” is “to assume a culture” he insisted.

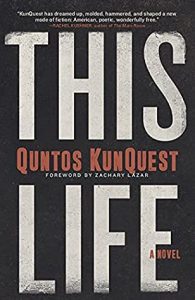

I started thinking about This Life, the debut novel by Quntos KunQuest set at Angola Prison, by trying to understand the word sentence, which has two meanings in the English language.

From the dictionary:

A) sentence is a set of words that is complete in itself, typically containing a subject and predicate, conveying a statement, question, exclamation, or command.

B) sentence is the punishment assigned to a defendant found guilty by a court, or fixed by law for a particular offense.

Having the word sentence exist in these two capacities is both telling and crazy. But then, it’s also telling and crazy that it’s impossible to see the forest because of the trees. Especially in the U.S.A., which has the largest prison population in the world, and the highest per-capita incarceration rate.

If something is obvious, like sentence and sentence, but also absurd, it keeps milling in the mind kernel by kernel. How do pairs like subject and predicate relate to law and order, how do the structural constraints of language and their internalization (or not) relate to crime and punishment? Wikipedia offers an answer in its first content point on the ancient history of prison: “The use of prisons can be traced back to the rise of the state as a form of social organization. Corresponding with the advent of the state was the development of written language, which enabled the creation of formalized legal codes as official guidelines for society.”

This Life by Quntos KunQuest is a work of fiction. It’s made up of a narrative, dialogues, and song lyrics that spin around one heavy fact that hangs from the ceiling of a concrete box like a naked light bulb without shade. The fact is without mercy, it is a life sentence, served not just by one man, but by many who (like words in a sentence) are put in close relation to each other. The men’s life sentences are lengthened and shortened by formalized legal codes, their days are structured by rules and routines. Spelled out abstractly like this, we recognize a pattern. It’s the pattern of social organization, hierarchy, and control, a system that has guidelines for everything, including bar spacing for prison cells, line spacing for a typed out paragraph, margins on ruled paper, a word count for a novel, a year count for a life sentence, etc.

In an essay for The Believer called “The Sentence is a Lonely Place,” Gari Lutz writes “The sentence, with its narrow typographical confines, is a lonely place, the loneliest place for a writer, and the temptation for the writer to get out of one sentence as soon as possible and get going on the next sentence is entirely understandable. In fact, the conditions in just about any sentence soon enough become (shall we admit it?) claustrophobic, inhospitable, even hellish.”

What does the hellishness of “narrow typographical confines” mean for a writer who serves a life sentence in prison? Does it even make sense to ask this question? Are there quotes that should not be taken out of context and be isolated? Are there people who should not be taken out of their community to be isolated? Can we say a quote is like a prisoner, condemned to stand naked on his (its) own, shackled in quotation marks? Quntos KunQuest writes:

This is for my people

Who feel snake bitten

For real

I’m feelin’ ya’ pain

Hopes decimated

Contemplatin’ ya’ situation

Compelled to get in the game

Who know the score!

No RulesThey makin’ ‘em as they go along

Play us like fools

I’m factin’ wit’ you

We winnin’ to lose

Who know the answers?

Sentence is a noun, what about the activity? What about sentencing — making sentences?

To be fair and accountable, a judge must impose a sentence that is sufficient, but not greater than necessary. In an interview with the Paris Review James Baldwin said: “You want to write a sentence as clean as a bone. That is the goal.” No extra time, no extra space, no hiding inside something meaty.

Quntos KunQuest writes:

Almost two years have passed since he arrived. He has heard it said often that the punishment should fit the crime. That the life sentence is justified when the prosecution has shown that an individual is incapable of functioning in society. That there is absolutely no way to rehabilitate him. How could that apply to him? He cannot yet put it in words, but it is clear to him that something about the so-called criminal justice system is backwards.

This Life is a written account of how life sentences are lived and spoken about out loud. The sentences are, as per dictionary definition, simultaneously the type A and the type B. They are written down as a product of the author’s mind and a product of the law. They are embodied by being lived, emboldened by their life-long length. Yet, despite the confinements in which the words of This Life came together, the language doesn’t feel locked up: the spirit is high, it flows back and forth and resonates, words shift on the page, tightly packed with an intensity that match the severity of the punishment under which they were written. The words, confined to the page, not only find space, they make it. Everything moves freely and with that Quntos KunQuest, who wrote his manuscript with a ballpoint pen on the backs of call-out papers in short breaks of “free” time, opens up my definition of incarceration, which in turn frees me, to a certain degree, from immediately having to feel fear first and foremost, when I hear the word.

Let this music ride the backs of oppressors

And promise breakers.

We refuse to be what you make us

What does that make us . . .

Chumps or victims?

Quntos KunQuest, who has been in prison for the last 25 years, has filled his novel with charismatic characters who have grown and matured in each other’s company. The story focuses on the relationship between Rise, who has already been spending many years in the system and Lil Chris, a new arrival. In a telephone interview with Susan Larson on New Orleans Public Radio, Quntos KunQuest explains that he modeled the fictitious bond between Rise and Lil Chris on the relationship that could have developed between himself and his brother, who died shortly after Quntos KunQuest was incarcerated, which drove him into desperation and near madness. Quntos KunQuest’s relationship to his dead brother, reminded me of Just Above My Head by James Baldwin, which is driven by the intense grief of an older brother, Hall, mourning his younger brother Arthur’s murder, trying hard to find a balance between love and rage. While KunQuest’s novel is focused on the present now, Baldwin’s novel often drifts into recollections and reminisces and at one point Hall describes the relationship to Arthur, “The Emperor of Soul,” as a double-edged sword: “One’s little brother begins his life (you think) within the sturdy gates of one’s imagination. He is what you think he is; he is everything that you are not; and he is, though you will never tell him this, much better, more beautiful, and more valuable than you. This is because you are here already, and he has just arrived. You have been used already, and he is newborn. You are dirty, and he is clean. You want the moon for your brother; you have forgotten that you must once have wanted it for yourself. Your life can now be written anew on the empty slate of his: what a burden to give your little brother!”

When Rise and Lil Chris meet for the first time in This Life, Rise immediately recognizes this potential, the potential to start something new.

Rise steps to him. “Say, big boy, what they call you?”

“My name Lil Chris, nigga. What, you know me from somewhere?” Vicious attitude. Gotta love that. Rise immediately recognizes this kid’s potential. He’s a soul-jah.

But it’s never just the two of them, the “empty slate” is nothing but one palimpsest among court papers, permission slips, books folders, and other palimpsests, which all reference, annihilate, and write each other’s stories. “The dormitory ledge is full, from one end to the other, with old victs and young cats.” There are A.U.’s, “soul-jahs with open wounds,” linepushers on horses, “correctional officers with nicotine and caffeine habits,” gangsters, brothers, rappers, and homies, who on certain days look “penitentiary sharp,” in some “Gucci loafers he got from the homie Hip City.” There are hardheads, gangbangers, and cellies, “who have enormous egos and are pretty good with their hands.” There is the block, “peopled by prayers and sinners.” There are “supervisors that pressure their female subordinates into dealing in sexual favors.” There are mentors, who are “Pushing the viewpoint. Feeling the response.” Snitches, go-getters, cynics, and believers who challenge, fight, or support each other into constitutions, that not only survive, but evolve and grow.

Legends and heavyweights alike spit poetic. They spit flames. Knowledge. Awakening. The realest say things that mandate studying and self-awareness to even understand, let alone to compete with. The legends provoke thought. They push people to keep up with them. The heads quote their lyrics in trouble situations like bible verses. Proverbs.

The setting of This Life, Louisiana State Penitentiary, Angola Prison, is the largest maximum-security prison in the United States. Angola has the largest number of inmates on life sentences in the United States. It is also a huge farm. Inmates cultivate, harvest, and process an array of crops that make the facility self-supporting. Crops include cabbage, corn, cotton, strawberries, okra, onions, peppers, soybeans, squash, tomatoes, and sugarcane. Each year, the prison produces four million pounds of vegetable crops. The name “Angola” comes from the former plantation that occupied this territory on the Mississippi River, which was named for the birthplace of enslaved people who were captured from the West Coast in Southern Africa and forced to work here. In the documentary Angola for Life, Jeffery Goldberg, national correspondent for The Atlantic says: “Today there is a reasonable chance that some of the men working this farm are decedents of the slaves who once picked cotton here.” In his book Solitary: A Biography Albert Woodfox, who spent 40 years in Angola in solitary confinement recounts the work on the farm in his autobiography:

Cutting cane was so brutal that prisoners would pay somebody to break their hands, legs, or ankles, or they would cut themselves during cane season, to get out of doing it. There were old-timers at Angola who made good money breaking prisoners’ bones so men could get out of work.

Quntos KunQuest describes picking okra like this:

“Not cool,” he drags on. “We go in that stuff, we gon’ be itchin’ fa days.”

Both of them only having only slept in spells through the night. The growth. The green. The mass. The smell of it is vaguely invigorating.

“Mayne they shoulda told us to wear long sleeves,” someone else complains.

“We ain’t just gotta put up with this shit. Nigga need to buck,” an anonymous voice urges.

Alot of people start talking at once. The line pusher doesn’t look worried in the least. Some cats have sat down, taken off their boots, and started ripping open the bottom seam of their socks. Making sleeves. The vast majority of them are simply moving to the trailer, grabbing their buckets, and waiting for the headline to count out what row they’ll be working. They’re catching their cut.

The Life was an enjoyable read, mostly because it was filled with hope, idealism, sincerity, and learning. Despite their struggles and their pains, Quntos KunQuest’s characters see society (or humanity) as a situation that can be healed and improved, which is inspiring. The men work hard to give back as fathers, sons, husbands, brothers, friends, artists, teachers, role-models, and a positive outcome of This Life is the proof that rehabilitation is capable of bringing change about.

To harness this young energy is the primary motive. To separate them from the degenerate, inhumane, and backward influences that prevail elsewhere in the prison. To isolate them. Debrief them in order to see what they understand. Initiate an unlearning process to clean out all of the errant, misguided, and destructive beliefs — hard, heartheld beliefs that they actually define themselves by. And, finally, to groom them in a way that will promote healthy self-awareness and more accurate objectivity. Ones they can lean on as they seek to redeem the time and choose their own path in life. Once these jewels are properly polished, they will be fed back into the populace. Both prison and society at large. To influence others toward conscious awakening and progressive attitudes.

I wish, I could end here, but I can’t.

That the characters, who had grown and healed and were deeply invested in being successful humans with good morals, lived in a maximum security penitentiary where many serve a life sentence without the possibility of parole for violent crimes they had (or had not) committed, was — after I had x’ed-out the e-book pdf — not a happy ending. Instead, once the book was shut, something disturbing took hold of me and dragged me down. Something was wrong. Maybe I had been deceived, or deceived myself? Maybe the novel didn’t describe the situation and its characters truthfully? I began watching documentaries about the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. I saw the massive farms, the horses and their riders with shot guns and pixilated faces, the vocational training centers, the peanut butter jar next to the apple jelly jar which granted a man his “last meal” before he was executed, the dormitories of 64 men and the cellblocks for extended lockdowns, hands reaching through metal bars, sneakers and churches, preachers and church services, funerals. Men, wearing crosses on their chests, who very much reminded me of Rise and Lil Chris and Gary Law, sat in circles and spoke passionately about their journeys. No, the documentaries backed up the fiction of This Life. There was nothing wrong with the truthfulness of the novel. Ugly, systemic wrongness had created a novel that was right and beautiful. Welcome to a particular branch of American absurdity.

How is a life gone guilty supposed to be corrected, if the sentence is life without parole? If the men (or young adults) who have committed murder, rape, armed robbery, or child molestation have over a period of 20, 30, 40 years worked through the horror of realizing what they have done, lived through the pain of their punishment, and then fulfilled the purpose of the correctional facility by becoming morally accountable, mentally reliable men, then why were they supposed to stay in prison until they died?

Isn’t a life sentence without parole like a wrong word in a sentence that is impossible to correct, condemned to exist outside of grammar and syntax? Is that one of the reasons of why Lil Nas X presents prison life in “Industry Baby” like a fun and highly entertaining mad house that leaves a terrible chill of wrongness? Is that why the video was released on July 23, 2021 together with a collaborative fundraiser for The Bail Project, a non-profit dedicated to providing free bail assistance to low-income people in jurisdictions around the country?

“Somebody’s gotta be hurt, murdered, killed, before we recognize the problem we have and go back and fix it.” says the Warden Burl Cain in the documentary Angola for Life that The Atlantic published in 2015.

Jeffery Goldberg, national correspondent for The Atlantic adds: “We’ve gone through a long period in America where its all about punishment and it’s all about mandatory life, but if you come here and you actually meet these people, you realize, or at least you have an inkling of a feeling that maybe there is something to the idea that the people they were when they killed other people, those people are gone, and that something new is taking root. When you look at the problem of mandatory sentencing not through the eyes of defense attorneys or liberal prison reformers, but from the warden of Louisiana State Penitentiary and he says, that this system is absurd, you really begin to see the maddening aspect of this problem.”

Livin’ blunted. I never stunted

The state is holdin’ me hostage and theOnly thing that’ll grant me liberation

Is the knowledge

I obtain.Underrated. My college?

Consequently . . . I been trained.Now, I’m searchin’ for my degree in pain

It’s a struggle thing

The strain, mayne. Reality?Is barin’ down on my back

But, I won’t pay attention

Cause I can’t let my high go.

The novel got out. This Life is roaming the American marketplace freely, touching those among us, who can choose what to read, where to read it, and when to turn off the light. The man who wrote This Life, Quntos KunQuest, remains locked up. As Zachary Lazar writes in his foreword: “He has been incarcerated since he was nineteen for a $300 dollar carjacking in which no one was physically injured. He is serving a life sentence for this one act.”

Franziska Lamprecht is an artist who started writing as an extension of the long-term process based works, she produces together with her husband Hajoe Moderegger under the name eteam. Their projects have been created and presented internationally and they could not have done this without the generous support of Creative Capital, The John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, Art in General, NYSCA, NYFA, Rhizome, CLUI, Taipei Artist Village, Eyebeam, Smack Mellon, Yaddo and the MacDowell Colony, the City College of New York, the Hong Kong Baptist University and the Fulbright Program. In 2020 eteam published their novel: Grabeland with Nightboat Books.

This post may contain affiliate links.