I first met Paul Griner when we were students in the M.A. program at Syracuse in the late 1980s—English with a concentration in Creative Writing, which was a thing back then. Paul was a year ahead of me, but we both were studying with Tobias Wolff and Doug Unger. It was an exciting place to be. George Saunders had recently graduated, and our peers included such writers as Lily King and Claire Messud and Tom Barbash, and everyone seemed mostly to get along well, even the poets. We went out for drinks together and had potlucks and so forth. Paul and I were both fathers of little babies.

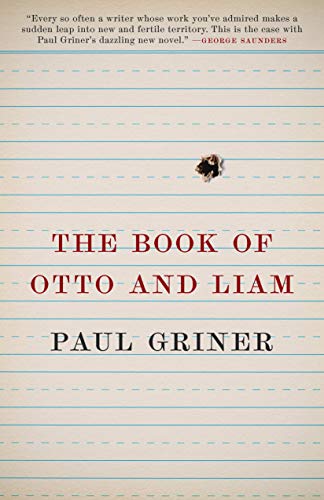

So I was super happy when Paul asked me to do an interview with him about his recent book. We hadn’t seen each other very often in the years since grad school, but I had been reading his books with interest and admiration, and I was very glad to get an advanced copy of his latest, The Book of Otto and Liam, which, I think, might be his best book. It’s a spooky, sad, haunting novel about grief and loss and speaks deeply to this particular American moment of denial and paranoia and rage—these pre-Civil War times in which we and our neighbors are all seemingly living in separate, alternate realities. Our conversation took place over email and phone during March and April of 2021.

Dan Chaon: I wanted to start out by talking about Sandy Hook. I find myself using it as a reference point when I’m describing your book to other people—“a man whose son is the victim in a Sandy Hook style school shooting is hounded by conspiracy theorists who believe the shooting was faked and he is a ‘crisis actor.'”

I wondered to what extent you expect that readers are going to make that connection to real life. Was the Sandy Hook Conspiracy stuff the origin of the book? What were the original seeds of the story, as you remember it? And also, how concerned were you with making your fictional universe separate from the events in the news? I noticed that there were almost no references to contemporary culture, despite the use of date stamps. (The one that pops to mind is the chapter that takes place in Nov. 2016, but makes no mention of…you know who.) In any case, I was super curious about your decision-making process in this, in part because I literally just wrote a novel that takes place in a slightly alternate universe because I didn’t know how to deal with writing about the actual contemporary America. LOL.

Paul Griner: So, origin story. I knew I wanted to write about school shootings for a while. As I’ve said elsewhere, I tend to write about things that scare me. That was just sort of in the background for a while, as I wrote other things. Then one day I awoke with the names Otto and Liam, and I knew Otto was the father and a freelance artist, and Liam his young son, wounded in a school shooting. I’m guessing that was before Sandy Hook, but I can’t remember exactly. For a long time, that’s all I had. I’d open the file and stare at their names. Then go away. Then come back. Then go away. It was my daughter’s accident that provided the way into the book, all the time I spent in the neuro-ICU. In fact, a lot of the hospital scenes in the book are directly based on my time there. Some, like Christmas For Beginners, are completely imagined, but the thing with the last will and testament and the ways doctors speak to Otto? Most of that I experienced. And of course the terror about your kid possibly dying. The intubation and possible pneumonia, etc.

Of course, in the aftermath of that, I started reading more about the school shooting. Columbine, Sandy Hook, and other mass shootings. It’s not that I expect readers to call up Sandy Hook memories, but it’s not that I don’t, either. That is, it wasn’t a conscious decision to echo Sandy Hook, but rather, just part of what all of us pretty much share now. The same way our parents would have known about Pearl Harbor or Kent State and Vietnam protests, the stuff floating around in the country’s collective unconscious memory. I knew I didn’t have to get too detailed in some ways, because people would be able to recall Columbine, Parkland, etc.

I did decide to get more detailed about the hoaxers though. They’re something we’ve all heard of, pretty much, but what they say and do? I think that’s not quite as well known. And it should be, really, the way the tragedy of that compounds the pain of the original tragedy for the parents, siblings and survivors. (Think Marjorie Taylor Greene harassing Parkland survivors.) So I researched that a lot, their websites, etc.

And you’re right, I didn’t mention much contemporary life. That was a conscious decision. I wanted dates, to give focus to the rising death toll in school shootings over a short period of time, and because anniversaries matter to all of us, especially those who’ve gone through something awful. But I also wanted this to be sort of free-floating, to have that feeling of having happened at almost any point in the last twenty years (and, unfortunately, I think, over the next twenty years as well) because it happens again and again and again. And probably will, once kids are back in school. (Sad sidelight: I read a tweet halfway through last Fall where a guy said his young son said, One good thing about the pandemic is we don’t have school shootings now.)

I didn’t mention Trump because I thought that Otto was so focused on his grief and anger and hunting down Kate that the politics wouldn’t really register with him. Other, more important things were calling to him.

I often find it hard to write about current events because I don’t trust my take on them. Plus so much of it has become so weird. So I understand your move in your latest novel, which sounds really interesting. Tell me more when you can.

So once you felt the book start rolling, what did the first 50 to 100 pages look like at the earliest stage? Was it mostly the hospital stuff? When did the Hoaxers show up for you? Did you start with short chapters and fragmented time-jumps, or did that come later?

I had the names early on, Otto a father and artist, etc., and in my first notes, I thought the book would be short, no more than 200 pages (375 now). I also thought it would move back in forth through time, starting with Otto getting Liam ready for school, and then the shooting right after he’d dropped him off, and then the hospital chapters would begin. But it would also have chapters from a couple of years later, many concerning the hoaxers, who were in my early notes too. Kate, the head hoaxer (at least in Otto’s mind) was in the first notes too, though as yet unnamed.

I began writing in March and finished the first draft in about six or seven weeks. The first chapter was a single page and it announced the fate of Liam. The second chapter was the family going on a ride to the orchard, the chapter that becomes the Full Catastrophe (an early chapter in the final draft). I knew Otto and May’s marriage would fail, and that Otto would meet a woman, but I knew nothing about her. Each chapter I wrote was short, right from the start.

I can’t imagine writing a 300-page first draft in less than two months. How exactly did you do that?

It was really fast. Another novel took me 10 years, so I guess it sort of balances out. My first novel I wrote a draft of in six weeks too. Though that was about 150 pages. Still, this one had lists and drawings and letters and texts. So, not a full 375 pages…And I think part of it was that I’d been living with the idea of this for at least a couple of years. Work going on beneath the surface.

True, but if you’re writing that fast a lot of it is coming out of a kind of subconscious place—you’re inside the novel like it’s a virtual reality headset. What were some of the things that surprised you or appeared unexpectedly?

One of the first surprises was a letter from a nun. It was a nice balm to balance the bile of the hoaxers. Her voice was calming and caring, steady, with wisdom that seemed earned. She came back twice on her own in the first draft, then more times when I went through it again. I’m not Catholic—was raised a peculiar mixture of Quaker and Episcopalian—and Otto is agnostic at best, but her voice reaches him. I was glad she was there, and able to do that.

Kate surprised me too. As I said, I knew hoaxers would be part of the story. I didn’t know how much, nor who would be their nominal leader, nor anything about her backstory. That all came out as I wrote and as I researched hoaxers and their websites/youtube channels, etc. (I have an entirely separate file with all that info; I didn’t want to store it with everything else from the book—the chapters, pictures, letters, etc.—as if it might infect them.) In any case, I came to understand her more, and her power, as she came into sharper focus on the page.

May surprised me as well. Her career wasn’t the one I thought it would be, and her steely resolve during the crisis of Liam’s hospitalization was a touchstone for Otto, and for me. In the aftermath, she seems to hold it together much better than Otto, until she learns of Kate, and that surprised me too. I’m not sure if Otto is surprised by what happens after he tells her about Kate, or if on some level he hoped she’d be able to do what he couldn’t—find and confront her. Maybe a bit of both. But that surprised me as well.

I was surprised by how quickly I wrote the first draft. And again how quickly I wrote a second draft that incorporated major revisions after having a friend and wise reader read it. Most days it felt like I simply sat down and opened a spigot and typed as fast as possible to keep up with it. That’s really rare, at least for me, and I remember being conscious of trying to enjoy that (separate from the material itself).

I think the final big surprise was how far the finished version traveled from my original conception. Re-reading notes I took before I began writing in order to answer your questions, I see so many things that have changed. All for the better, I think, deepening the characters and moving through many more emotional registers, and farther away from the source material than I’d thought.

I meant to follow up on that question about how to write a draft in 6-7 weeks. What’s it actually like in the day-to-day? Did you have some kind of crazy strict schedule? Were you on a retreat? Living in a remote cabin? Did you have someone bringing you food and spooning it into your mouth while you typed?

No retreats, no cabins.

I’d messed up my back pretty good on a construction job in my 20s. Slipped a disk and we were thirty miles from Syracuse and it was first thing in the workday so they put me on sheet of plywood in the back of a pickup truck while they worked and I was driven home that way when the day was done. For about a dozen years the disk would pop out once a year or so. In my late 30s it didn’t go back in, so I needed surgery. I had a six week wait in bed. I wrote Collectors during that wait. I’d prop a pillow under my head and my laptop on my chest and just type. Six weeks straight, not a day off. Food brought to me for that one, but I managed to eat it all by myself.

For Otto and Liam it was a similar schedule. I didn’t take a day off for any of the weeks, though Saturday and Sundays I’d work fewer hours. Rolled out of bed every morning and just started typing. A late breakfast/lunch/brunch, then a walk, then more writing until dinner. Sometimes after dinner too, though not too often. I sort of resented having to sleep. But I suspect everyone here sort of resented me. I didn’t do much cooking or cleaning or anything you’d expect to do. So, I was lucky. I believe I chewed all my own food for this one too.

I’m super interested in what you’re doing with all these formal devices, and I’m curious about how they came about—the drawings, lists, letters, and so forth. I was also surprised and excited that you use chapter titles. ( I did the same thing with my new book, and I’m not exactly sure why except that I love titles, and the prospect of coming up with 44 of them was really fun. It gave me the mood of putting together a record album…or a story collection, shh.)

In my early notes, I have the idea for lists, statistics, and letters, all of them only a page. The drawings came later, when I was trying to figure out Otto as a person. I got books to teach myself to draw and practiced a lot, and then some of the drawings seemed like they should be in the book. Some still are, but I also realized I needed some to look like they were done by a professional, so I worked with a former student who’s an artist and talked with her about the book, what I wanted, how it should look, and she’d come back with three or four mock-ups for each drawing, and we’d decide together which ones she should complete, except for a few, such as the first one of Liam holding apples, that I knew were perfect from the start.

The idea for the titles was there from the start too, though very different. I was going to name each chapter after a child who died in the shooting, just their first names at first, as a way to honor them. Then their whole names. But I realized their names weren’t mine to use. Still, the idea of chapter headings stuck, so I started to try and figure out what they would be.

Can you talk a bit about how the structure of the book emerged for you?

My most recent book before Otto and Liam was a collection of stories, Hurry Please I Want to Know. I printed them all out, laid them on the floor and shuffled them around repeatedly, until I had the order I wanted. I knew the first and last stories, but the rest I needed to do by feel and intuition. Putting these chapters together was sort of like that.

I pretty much knew the first few chapters, knew from the start the arc of the book would be about nine months—Fall to Spring (more light toward the end of it)—and I knew the chapters would echo each other (past and present) following roughly that nine month timeline. But the letters, texts, lists, drawings and some of the chapters themselves, well that order changed many many times, both as I wrote more chapters and as I revised, cut and assembled the finished manuscript.

I’d like to talk a little bit about genre. I think this book could be categorized as a thriller or crime novel (so could two of your earlier books, Collectors and Second Life). I wondered what your relationship to genre is—as a reader/movie-watcher, etc.? Attitudes toward genre writing have changed enormously since we were in grad school at Syracuse together, but there are definitely separate communities of writers, still.

I’m a promiscuous reader/viewer. I consumed the Hardy Boys and comic books as a kid—Marvel, not DC—and the first “real” novel I loved was The Great Gatsby. Over the next twenty years, here’s a highly abbreviated list of fiction writers I came to love: Hemingway, Austen, Morrison, Baldwin, Cather, Melville, Twain, Mansfield, Machado de Assis, Hurston, Borges, Garcia Marquez, Lispector, Barker, O’Connor, O’Connor, Turgenev, Wright, Ishiguro, Lem, Le Guin, Wolff, Woolf, Dos Passos, George Eliot, Butler, Murakami, Bender, Mosley, Kincaid, Jewett, Walker and Connie Willis.

One of my favorite movies is Breaker Morant. Others include The Lives of Others, Biutiful, The Rider, The Man Who Fell to Earth, Boyhood, The Piano, Moonlight, Moonrise Kingdom, The Hurt Locker and Jean de Florette. But I’m just as happy watching Saving Private Ryan, Witness, The Fugitive, Dumb and Dumber, Happy Gilmore, Wall-e, Children of Men, Devil in a Blue Dress. Wallace and Gromit and most of Mel Brooks. So, thrillers, sci-fi, dramas, comedies and animated films. The two series I’ve watched most recently and really loved are House of Lies and Bosch.

Are there thriller/crime books that influence you?

More writers than books. Capote’s In Cold Blood and Hand Carved Coffins are both nonfiction crime novels, and both ones I’ve reread often. One of the things I love about HCC is Capote’s desire to use all the types of writing he’d ever done in a single project: fiction, nonfiction, reportage, screenplays, etc. It wasn’t a conscious decision, but I’m sure that his use of so many different genres in a single extended piece influenced the way I structured Otto and Liam, just as the structural experimentation of Dos Passos’s USA Trilogy (a non-thriller) did. Eric Ambler? Love him. Elmore Leonard too. Would Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist qualify as a thriller? Pat Barker’s Regeneration? I love both of those as well, and the tightness of both narratives, the emotional pressure the characters are put under, is something I admire and strive for. I really like Kate Atkinson’s Jackson Brodie detective novels, but if one of her books influenced me, at least while writing this book, it would be her “literary” thriller, Life After Life. Lee Child is a lot of fun, Don Winslow terrifyingly exact about what the “War on Drugs” has cost in terms of American and Mexican lives, and I love Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins series, just as much as I love most of his novels, because they’re brimming with life. I was conscious as I wrote Otto and Liam that I needed a lot of humor, a lot of tenderness and love, to balance its darker aspects. Mosley understands that as well as anyone writing today, I think.

As I was reading both Await Your Reply and Ill Will I wondered about that question for you too. Apparently separate but intersecting narratives, the ellipses, chapters that end on sentence fragments, the fugue state that the narrators enter into, pausing the narrative, prose laid out in parallel columns, where did those come from? Crime books? Literary novels? Not sure, and perhaps it doesn’t matter. Everything feeds everything else. In a way, your novel Await Your Reply anticipates this shift in thinking about genre. Identity is fluid, and hard to really nail down. And perhaps it doesn’t need to be.

How do you feel about the issue of genre, and has that changed over the years?

We weren’t studying Octavia Butler, Kurt Vonnegut, Elmore Leonard, Karen Joy Fowler or Stanislaw Lem when we were in grad school at Syracuse, even if we were reading them, but that’s changed in English departments around the country, as has the narrow classification of writers to some degree among publishers. Both changes are for the better. For instance, both of your novels Await Your Reply and Ill Will could also be called thrillers or crime novels, since they both have crimes at their cores and in both part of what drives readers on is the desire to find out what’s true, who’s guilty, etc., and yet, aside from the numerous disasters that befall the characters or that they help land on others, neither novel would be fully comfortable stuffed into the same closet as books by, say, Tami Hoag or Dwayne Alexander Smith. So, are they cousins? Kissing cousins?

Personally, as I note above, I’ll read anything if I think it’s good; once past high school, I’ve rarely cared much what others thought, which is something I’m often secretly proud of, and also something I know can veer into the stupidly stubborn. But I believe that genre is in many ways more of a marketing decision than an intellectual distinction, though I understand and sympathize with publishers’ need to figure out how to sell things.

Yet I know one writer who turned in a manuscript to her agent, who said, “If this is a novel, I can get you $X for it. If it’s a memoir, add a zero.” So, it was published as a memoir. And another who told me her first novel was just outtakes from her life, written down in a series of discrete essays, that her editor helped put together as a novel. And how do you characterize Anne Carson’s Nox? Isn’t the boundary between prose poetry and flash fiction pretty elastic? The Way to Rainy Mountain, Pride and Prejudice, Pedro Paramo, Cane, Half A Yellow Sun, House On Mango Street, Moby Dick, The Color Purple, The Sorrow of War, Dom Casmurro, Song of Solomon, Huck Finn and Nightwood are all great books, and all “literary” novels, but are they really all the same genre? That baker’s dozen might make a great syllabus for a course in which to examine the issue.

I think you can grade all novelists on a continuum. On one end, there are the novelists who believe humanity’s nature is essentially evil; on the other end are those who think people are essentially good. Most are somewhere in the middle. Maybe you could say that there’s a scale of optimism/pessimism that we all fall under.

Well, I’d guess I have a darker view of humanity than most, though perhaps not as dark as yours. But, speaking for myself, my dark view makes me weirdly optimistic. I don’t believe most people are either essentially evil or good; instead, I’d argue that people have the capacity for good and evil, and it’s often a fine-run thing which way they fall. And that it can change, with circumstances and over time. It’s sort of like the question people used to ask when we were younger. Are you a Beatles fan or a Stones fan? I always went for both.

So for me, even nearly the most reprobate among us can be rehabilitated, can change, can, perhaps, be redeemed. If we all have the capacity for darkness within us, then perhaps we can all push away from it toward the light. I will admit I’m suspicious of grand transformations, and that I don’t think all redemption quests succeed. The Washington Square Ensemble details the lives of four “pharmaceutical salesmen” in Washington Square Park, before the area had been gentrified. Very early in the book, one of the dealers goes to a client’s apartment because they owe him money. They have an infant. He grabs it and holds it out the window, many stories above the pavement. The addicts know he won’t drop the baby. Who would? They laugh at his pitiful attempt to intimidate them into giving him the money they owe. He drops the baby. That novel is really good, but as soon as I read that passage, I thought, No way this guy can be redeemed. And, to my mind, he never is. On the other hand, by the end of Beloved, we understand why Sethe killed her own child, which provokes a mixture of enormous sympathy and enormous anger, not at her, but at the world that drove her to take such a step.

I feel like that question is actually a huge tension in your novel, and often in play in contrasts between scenes of enormous, gleeful cruelty and moments of grace and kindness, to the point where I felt like that was a deliberate plot element. Which view of human nature would prevail? It seems like you were struggling with it as you were writing.

Yes, it developed naturally, that whipsawing of the characters (especially Otto and Lamont) between those two extremes, and I was anxious to see where it would end up. When I started the novel, I wasn’t sure where it would lead, and, while it was heartening to see Otto bottom out and begin to rebound, it was just as distressing to discover that, for Lamont, there was no floor to grief and rage. Maybe they’re the two sides I suspect lurk in us all, the two sides to me, constantly fighting it out in my work.

But, to end on an up note, I was happy when the nuns showed up in the novel, and when Palmer Skutch did too. She’s the woman Otto begins to date a couple of years after his marriage falls apart in the aftermath of the school shooting, and he’s with her at the end. May too seems to have found someone, Nash Barnes, the lead detective on the case. So, even after tragedy, the book offers hope. Beatles over the Stones, by a nose.

How do you create characters? I feel like Otto is an avatar of you—that you poured a lot of yourself into him. But obviously this isn’t an autobiographical book, and most of its characters are not simply versions of your friends and neighbors. I wondered how you go about trying to imagine yourself into people. For me, I often use the Orson Welles Mercury Theater model. Welles had a small stable of actors that he would regularly cast in widely varied productions, and I sort of do the same thing: people I know well get cast in different roles, you know. “In this novel, the confused high school girl will be played by my sister, Sheri, and in this other novel, she will play the cagey cousin, and etc.”

Damn, wish I’d known the Mercury Theater model earlier. Would have saved me a lot of work over the years.

But sure, there’s a lot of me in Otto. Or Otto in me. Lucky for him he’s better at art. Yet he’s not just me. He’s also other people I’ve met or read about or imagined or overheard in hallways and stores and on subways. I listen a lot. I take down lines of dialog, ones that seem striking in and of themselves or that reveal a lot, perhaps unintentionally. I have whole notebooks of those, and of descriptions of people, landscapes, buildings, weather, etc. and sometimes when I’m working on a chapter or a story I’ll crack some open and read through them until a line of dialog or a description sets something off. Some of the lines of dialog in the book are directly from those notebooks, and some of those led to entire chapters.

I also find a lot of times that when I’m working people seem to be speaking for my benefit. That is, I’ll be pushing the cart around the produce aisle or among the frozen food islands and someone trying to figure out if a pineapple is ripe or choosing which frozen shrimp to buy will say something on their phone or to another shopper that is exactly what character X would say. I make a lot of stops in the grocery to type notes into my phone. I try to be discreet about it, so people don’t realize I’ve just vacuumed up part of their lives. But you also can’t help using people you know well as models, however tenuous the connection between them and a character. What they’d say or do in a situation? You can intuit that.

There’s a quote early on that haunts me. It’s the letter the Sisters of the Most Sacred Heart of San Diego send to Otto: “You do not know us, but you have been entrusted to our care.” I can’t stop thinking about it. It feels like it applies to so many different situations in the book.

It also weirdly applies to the attitude of the hoaxers. I found myself hating them so much. I have to admit that part of the suspense of the book for me was about strongly wanting to see them hurt, and you’re very cagey about how you manage that.

Well, thanks. What hoaxers do is so awful, a compounding of tragedy, that it’s hard to feel sympathy for them. And of course much of the book is Otto’s, but others, such as Lamont and May, are also confronted by hoaxers, and it’s crushing for them. Crushing and infuriating. How could it not be? You’re dealing with immense grief over something so awful, and then you’re told it didn’t happen? Not only told, but hounded, so you’ll admit as much? I wanted the book to evoke anger in the readers, at least in those passages, because I want them to identify with the characters, the desire (for those three, at different times and in differing amounts) to hunt down hoaxers and hurt them. At various points it’s what drives them on, and I hope part of what drives the reader on too.

As I researched the hoaxers, I didn’t come to like any of them, but I did come to understand some of them, the ones who have a peculiar sort of self-awareness, who say, I’m not wrong, but if I were, I’d be one of the most monstrous people on earth. They often repeat that, from interview to interview, like a mantra.

That seems especially true of ones who at first believed the shootings to be real, who in some cases donated money to survivor funds, but who came to believe, for whatever reasons, that they’d been duped. They’re often the most active, the ones who not only write the most—on their blogs, or by letter, text, or email—but also the ones who show up to town board meetings, demanding to see school surveillance videos from shootings. When they don’t get to see them, for obvious reasons (in most peoples’ minds), they’re extra vocal about how that “proves” it’s all a hoax. That feels like psychological armature to me; they can’t admit the slightest doubt and have to yell at others to silence their own questions. Otherwise, they’d have to face what they’ve become.

And some simply seem to have their moral compasses set wrong at birth. You’re not a benevolent person, one hoaxer writes Otto, after they’ve written him threatening letters and he’s turned their name over to the police. A lot of real hoaxers are like that. They’re just trying to prove the truth, in their minds, so they can’t see why anyone they go after would be angry.

I’m intrigued by your feeling that that line from the nuns applies to so many things in the book. I think I know what you mean, but could you write a little more about that?

You do not know us, but you have been entrusted to our care. So much of this book is about the longing for connection, and the lack of it—the desire for community, and the loss of it. I’ve often worried that the concept of community has been deeply degraded over the past ten years or so, as we’ve given over huge chunks of our lives to social media, and our interactions with people have replaced by an online simulacrum that flattens us and turns us into video game versions of ourselves. First person shooters, hunting for an enemy: the hoaxers are like malevolent versions of the nuns. You do not know us, but you have been entrusted to our harm.

This is such a lonely book! It gets at the free-floating, deep space nature of grief, and it makes sense to me that it grows heavier as the years pass, rather than lighter. There’s a growing horror that the hoaxers aren’t ever going to stop, that they are searching for something they’ll never find, just like Otto and May, Nash and Lamont.

Frank O’Connor once wrote about the peculiar sweetness of Americans toward strangers, which he saw as linked to and an outgrowth of our essential loneliness. I think he’s probably right. In the second Borat movie, Borat moves in with a couple of guys for a while, after just meeting them in some southern town. Believing he’s a foreigner, lost and confused, they take him in, an act of kindness and generosity. They’re also happy to sing along with others about killing Democrats, both voters and politicians, at a Trump rally.

The two of them may not be rootless—they may have grown up in the same town they now live in—but they probably know lots of people who are. And they’re probably lonely too. The “info” they have about Democrats and about northerners seems likely to have come from Fox News and the Internet. If so, as you say, they aren’t really interacting with people so much as having their own biases upheld and reinforced by proxy. Maybe those wouldn’t stand up to real human contact.

So many Americans move away from hometowns, from family and friends, in search of better jobs or more exciting lives, because we want to or because we have to. In Ill Will, Kate and Wave are desperate to get out of their small town as high schoolers, while their cousin Dustin seems mostly content to grow up there. Then all three have to leave after their parents are murdered, and end up with a relative they hardly know in the Nebraska panhandle. They get out of there as fast as they can, too, and end up scattered all over the country.

Kate and Wave are twins, but are barely speaking before the murders, and lose all contact after. All three of them are lonely; some of them have families. But they all feel rootless. And Dustin’s son Aaron, an addict, ends up scoring drugs at a former funeral parlor, the House of Wills. While there, he moves through time parallel to his friend Rabbit—either a suicide or murder victim—and another character, who appears to be a ghost, and who can tell how soon others are going to die and whether their deaths will be calm or awful. They’re all trying to salve something. I’d argue it’s a combination of grief and loneliness.

And I’d agree with you that that loneliness is compounded by the rise of social media over the last decade, which makes it harder for all of us to truly process our grief. A parent or sibling or spouse or child dies, and, if you’re far away from friends and family, you have very few people to actually talk about it with who directly knew them. You don’t pass the places you used to picnic or where you first kissed or learned to ride a bike or broke your first bone. Memories are tied to places, but if you leave those places behind, the memories degrade, and the emotions attached to them slip away. Otto has to move after the shooting, because of the hoaxers, but in doing so, he’s sacrificing a lot of his past.

And maybe both the nuns and the hoaxers are trying to connect, to form a community, through vastly different means. I know which I prefer, but perhaps what drives them isn’t really that different.

I want to avoid spoilers, obviously, but there are some huge pieces of withheld information that come out in the last quarter of the book, and I wanted to ask you if you could talk—without revealing too much—about your decision making process as you arranged the chapters? Did you know from the beginning, or did you find out at about the same time the reader does? How did you manage it?

On second thought, maybe we shouldn’t mention the withheld information at all—I don’t want to ruin anyone’s experience of the book.

I can talk about the withheld info, without revealing too much, I think.

Everything that comes out over the last 50 pages—which answers readers’ questions about the fate of certain characters, or which clarify things which people might not have even realized were obscure—I knew about, as a writer, early on. In the first draft, one big piece of information was on the first page, but it robbed the book of suspense and surprise. So, I made the changes carefully, in the next draft, to keep the reader guessing. Withholding information like that can make it much more powerful.

Another thing that contributes to the sense of loneliness is the lack of contact Otto and May have with their families. There’s hardly any mention of parents or siblings and both of them seem deeply dissociated from any memories of childhood. I found that disturbing, how disconnected they seemed from their pasts and their family history. Why did you choose to avoid their childhoods?

I think much of it is due to this: nothing from their pasts prepared them for this. Both, in my mind, had largely happy childhoods. And while childhood memories can sustain us in times of peril, the one that comes to mind for May is the one that she now thinks led her to marrying Otto (and thus to giving birth to Liam): when a cop was trying to find out if she’d been drinking while underage, and missed that she had. She wishes he hadn’t, that she’d been arrested, because it would have sent her life on a different trajectory. She’s not looking to her past for sustenance, in other words, but for clues as to how she ended up with everything going wrong.

Otto didn’t have siblings, and his parents are both dead (at one point Liam asks why Otto’s mother was burned up during her cremation), and, given that he’s moved repeatedly for his job like many Americans, or for May’s, he’s largely disconnected from both his past and from his current hometown. His roots are shallower than a Willow.

In that way, the book is almost the inverse of Ill Will. In that, Dustin’s past includes the murder (or murder/suicide) of his parents and his aunt and uncle. How could that not have marked him, and be ever-present in his thoughts? More importantly, that past directly contributes to all the other horrible things that befall him in the present; the past and present are one unbroken stream.

In Otto and Liam, the school shooting severs Otto and May from their pasts, rendering nearly all that’s come before insignificant. They have to deal with Liam’s wounds and his attempted recovery, and, after that, with those who deny any of it ever happened. They haven’t got time for the past, or, really, for much of a future. They’re trapped in the now, like bugs in amber.

In the context of this terrible isolation, the Hoaxers have an almost supernatural power—they are like malevolent ghosts or demons, and they infuse every scene with an ominous quality, whether they are in the scene or not. They might be hiding behind any seemingly innocent detail!

Yes. They haunt the characters, and the book, though they’re not often on the page. That was intentional. To me, hoaxers are like force-multipliers, in the damage they do to mass-shooting survivors and their families (and, by extension, to society at large), damage that’s hard to overstate. That’s the world Otto and May and Nash and Lamont have to exist in, which drains and upsets them.

I kept trying to imagine what I would do, and I thought that I would go to everybody in my community for help. I would tell my neighbors and talk to my mailman and try to get as many people on my side as possible.

But Otto mostly keeps the torture he’s going through a secret, almost as if he’s ashamed, as if people might side with the hoaxers. Why do you think he’s so unwilling to ask for help?

In part because Otto hasn’t really become established in the town before the shooting. They’ve just moved, and so he doesn’t know a lot of people. Also, before long, he’s out of the house and moving from place to place, in part to keep ahead of the hoaxers, but more, I think, because no place feels like home after his family falls apart. He probably doesn’t know his mail carriers, since he moves so often. But your larger question is, Why not ask others for help? He does tell Nash, the detective. But he doesn’t want to burden May, and he and Lamont are trying to deal with them on their own. Law enforcement is slow in such cases, as much as they’d like not to be, and Otto’s tired of that.

And you wisely touched on shame. Early in the book, Otto mentions how Kate, the head of the hoaxers, originally came to his attention through videos she’d made questioning the official 9/11 story. He hadn’t really believed her, but he’d flirted with the idea that something more nefarious was at work. Now that the school shooting in which Liam was wounded and Latrell died is being questioned, he feels both shame and guilt that he’d ever doubted those who spoke of their grief in the aftermath of 9/11.

He knows how the slightest discrepancy in official versions can lead to people questioning the veracity of an entire event, so, while his fury at the hoaxers is well-deserved and often consuming, perhaps a very small percentage of it is self-directed, for his former beliefs.

So, the natural way to end this is to talk about what’s next. Another novel?

A novel and a collection of stories. The stories are farther along, with some already completed, and are vastly different than the novel, and vastly different from than Otto and Liam, as well. Some of the stories are set in Nigeria, others in Europe, one in Singapore, and the final ones around the US. The characters are linked, sometimes in obvious ways, sometimes in ways more tenuous, but all are dealing, however tangentially, with the cascading disasters stemming from climate change. The novel is still too early to talk about.

How about you?

I’ve got a new novel called Sleepwalk coming out in April of next year. It’s supposed to be funny. Plus I started a new novel, kind of a Western. Since I retired from teaching, I have nothing better to do.

A kind of Western? Cool. Can’t wait to read them both.

Dan Chaon is the author of six books, and has a new novel called Sleepwalk due out from Henry Holt in April 2022. He lives in Cleveland with his dog, Ray Bradbury.

Paul Griner is the author of six books, including the recently released The Book of Otto and Liam. He teaches at the University of Louisville

This post may contain affiliate links.