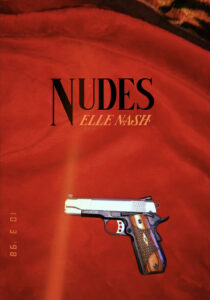

[SF/LD Books; 2021]

The world is a ruthless place, and its people are cruel people. But if one looks beyond the ugly, there can come moments of deep human compassion — where our ugliness doesn’t seem so absolute after all. I felt this reading Elle Nash’s Nudes, her new collection of twenty-four short stories. Like her debut novel, Animals Eat Each Other, Nash’s main concerns lie in desire, from the purest to the most brutal. Nash’s stories, which are often a spiky and equal mix of thrills and melancholy, develop across run-down apartments and suburban homes, and are populated with characters who are now ready to pull the trigger. Because above all, her characters are resilient. Though they may be prone to violence, not always to another person but certainly to themselves, it is their strength and desire to persist that take center stage. At times electric and restrained, at others tender and piercing, the collection is immensely compelling.

In “Ideation,” a woman recounts moving into the apartment below “the girlfriend.” She quickly grows transfixed, insinuating herself into the girlfriend’s life. But what is the girlfriend hiding? Should we fear her? Is she dangerous? No — quickly, the tables are turned and it is revealed the neighbor is the one that is fearless, that she is the one with nothing to lose: “Now she wasn’t afraid of death so much as she was scared of running out of time,” writes Nash. Nothing is quite as it seems in these stories, where the soft-faced boyfriend is capable of abuse (which is not surprising at all) and the neighbor downstairs is capable of murder. Many of Nash’s characters are capable of violence. In one story, an old man dies and the woman who lives below him considers burning his apartment down like a funeral pyre. In another, a fantastical piece of flash, a woman swims through the veins of a blue whale, a story that is both a container for a quick, epic romance and a slice of body horror.

Beyond desire — for sex, love, connection, simply a better life — the characters in these stories have much in common. They live with angry men, are pregnant, bulimic, alcoholic, and suicidal. They are nearly all working class and white, and some are identifiably queer, too. These are stories of characters along the margins, stories that offer visceral glimpses into the texture of their lives, capturing what may be one of their more singular moments. Often, we encounter her characters in what we assume is an important time in their lives, something defining, a juncture of significance. Shortly, we discover that this is just life, and this moment is not extraordinary, but there will be others like it. As a guiding force, Nash has also divided the twenty-four short stories into six sections: Fluffers, Yuri, Pukkaki, Moneyshot, POV, and Snuff. Though the stories share personalities, the characters all living in the same world, facing similar problems, having similar traits, and grappling with the same unwieldy bodies, the titles of the sections emphasize the focus of each story. This is helpful in a collection where similarities persist, and, in my opinion, only furthers Nash’s thesis that we are all just human, suffering from the same base maladies.

The stories in the “Pukkaki” section are the ones that most closely center the experience of living with disordered eating. The protagonist in “We Are Sharp Edges Bumping Against Each Other” studies her thigh gap, “the space between her legs is where a thousand moments lie.” In “Define Hungry,” we meet a woman in financial turmoil, only to discover how large a part of it is a result of her bulimia: “In the past year alone, I’ve thrown up at least five thousand dollars’ worth of food. Body by bulimia.” And in “Livestream,” a woman purges to an audience from her camera, where “the sound of a cartoon coin being collected rings from the phone”— she is being tipped. But a standout in this section is “Thank You, Lauren Greenfield,” where the protagonist muses, “Some of my earliest memories are of feeling bad.” She grows obsessive over the documentary Thin and attends AA as therapy for her eating disorder. She confesses, “I am addicted to bodies. I am addicted to consuming bodies. I am addicted to my body, comparing my body to other sick bodies. I am addicted to consuming things and then ridding myself of them.”

“It seems you may be addicted to addiction. To identifying as an addict,” a friend and mentor later responds after reading the protagonist’s writing on her eating disorder, which could be the story you’re reading. But in stories where bodies are represented as slippery things, the definitions used to prescribe meaning feel similarly cumbersome, nearly obsolete. The protagonist is an addict, yet that description doesn’t feel particularly accurate, not when the experiences rendered cast the kind of net that reflects on the entire human experience. What lives on the page does not necessarily feel singular, but often universal.

At another point, the protagonist describes her partner’s ex-girlfriend, who was anorexic and, for a brief moment, her best friend: “When I say ‘best friend’ what I mean is we starved together for several years and got to our lowest weights together, before the two were ever dating. It was very romantic. Meaning I romanticized it heavily.” I think it’s true for most of the stories in the collection that the characters fall prey to having romanticized something. Then, they are hit with the cruel truth that life does not actually operate in such a way. What can be beautiful one moment can be ugly the next, if it was ever truly beautiful to begin with. The stories are a puzzle box in that sense, where our understandings of a character are ever-shifting the further we delve into their psyches, becoming mirrored and mottled and yet gaining clarity and precision as well. There is a gratifying lucidity achieved in many of Nash’s stories. Characters’ desires become clearly communicated, as are their motivations, which leaves little room for ambiguity. A large part of this is a result of Nash’s sentences, which live in a state of near-perfection.

Another standout in the collection is “Cat World,” a coming-of-age story that tells the tale of two relationships, one that evolves across a chat room, and one that evolves offline. Both take dark turns. At one point, Nash writes, “The problem is you find a place you think you might belong and want to violently wedge yourself into any open space warm enough to welcome you.” The characters in Nudes have the tendency to become obsessives. Though, isn’t that true of us all? Nash’s preferred mode is often stark, as seen here, but it is always striking as well. She thoughtfully draws out moments in her characters’ lives that inch towards transcendence. Her characters think they are at a crossroads, with desires that become all-consuming before sometimes evaporating. And when carefully tied together, these moments speak a kind of truth that is rare in fiction. Her characters ask: despite its disappointments, life is beautiful, and why should I change? Or worse: can I change?

In “Room Service,” the final story in the collection, the protagonist begins: “On our wedding night David shows me what it takes to kill a man.” Though, it’s a bit of a red herring. She is referring to her husband’s propensity for watching snuff films. Nash writes, “David opens his laptop and navigates to a website full of recordings like this: a video of a man being burnt alive in a cage, his body going taut and black; a video of a man getting shot in the head, a cavity the size of a fist blowing out the back of his skull. There are a lot of things I don’t know about my new husband.” In a collection where the protagonists are often positioned close to violence, this story feels particularly different: the protagonist is positioned as a spectator, much like a reader. It almost feels like a nod towards the reader’s experience over the course of the twenty-four short stories. In that sense, it is both self-aware and a fitting closing story.

A little later, the protagonist muses, “I had always wanted to date a man I thought might murder me.” Nash is excellent at fanning her stories with these incredible, weighted lines. They suddenly raise the stakes and introduce a kind of playfulness. Again, Nash mines for gold in her sentences and often succeeds. In another story, a character considers how, “Lately everything feels inconsequential. Experiences fall through me like a sieve. I consider accepting custody of my sister’s baby. I consider abandoning the dog.” And in another, “The nurses say my name is Amanda but I feel more like an Angel.” There are many more examples.

In Nudes, the characters live in a moral gray zone, not unlike most humans. The sex is barbed with violence, but that does not mean there isn’t a kind of tenderness present. Certainly, the moments in which characters do bond and feel the most seen are the most tender. Ultimately, Nash has created a spiny and sobering arrangement of characters outside the urban landscape prioritized in contemporary literature, which is refreshing in itself. She illuminates her characters’ behaviors with sharp and empathetic prose that strongly evokes all their deepest longings, with all their inherent discontents. But each story also opens the door to the possibility of transcendence, which, in turn, suggests the possibility of victory.

Josh Vigil is a writer living in New York.

This post may contain affiliate links.