J’Lyn Chapman is the author of To Limn / Lying In, out from PANK books, Beastlife from Calamari, and the digital chapbooks A Thing of Shreds and Patches and The Form Our Curiosity Takes: A Pedagogy of Conversation from Essay Press. The first time I read Chapman’s newest book, To Limn / Lying In, I noticed many uncanny parallels with my own lived experience and writing life. This Spring I began teaching her book and Chapman and I corresponded by email about grids, devotion, and the process of writing that begins with ritual.

J’Lyn Chapman is the author of To Limn / Lying In, out from PANK books, Beastlife from Calamari, and the digital chapbooks A Thing of Shreds and Patches and The Form Our Curiosity Takes: A Pedagogy of Conversation from Essay Press. The first time I read Chapman’s newest book, To Limn / Lying In, I noticed many uncanny parallels with my own lived experience and writing life. This Spring I began teaching her book and Chapman and I corresponded by email about grids, devotion, and the process of writing that begins with ritual.

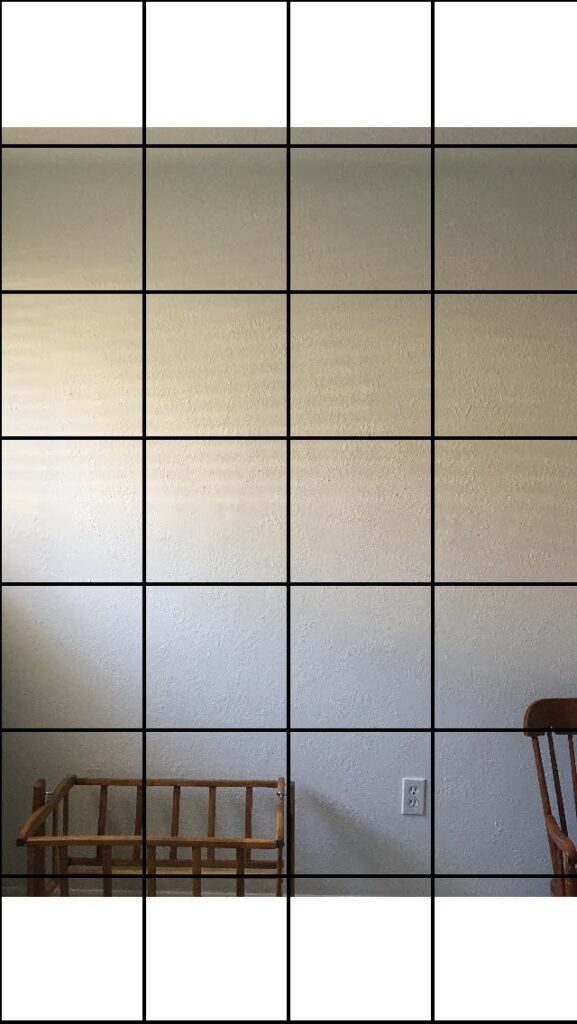

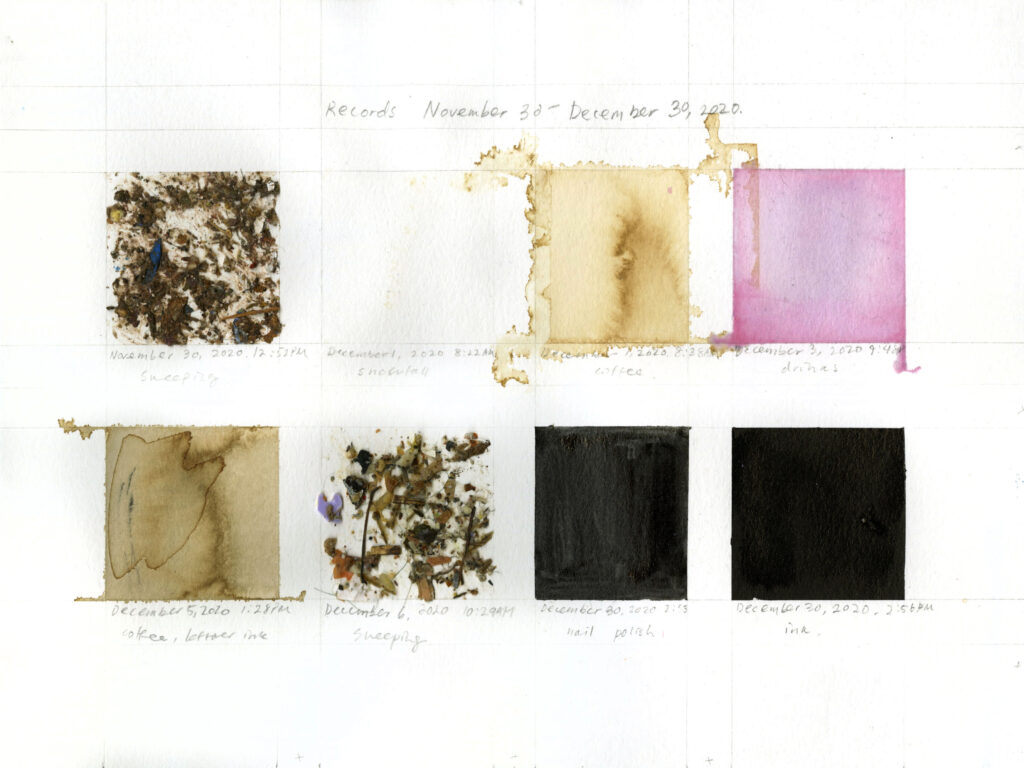

Paintings by Jace Lee

Sarah Minor: Your writing often comes in the form of essays, and often engages directly with poetry and poets. Can you talk a bit about your work within and across traditional genres? Before you begin writing, or during, do you think about whether you are writing an essay or a poem?

J’lyn Chapman: I usually have an idea and try to consider what form the idea should take. And often I experiment with a few forms before settling. I do think of To Limn / Lying In as a book of essays, but they feel as if they are nearly poetry or like they share molecules with poetry. I mean I have fussed over every single word of that book as if it is a book of verse, and in terms of duration it feels like it is the length of a book of poems. I admit that I do not feel as comfortable writing lineated poetry as I feel writing prose, so I employ verse in a kind of reckless way. I try to make my sentences sound like lineated lines without laboring over the actual lineation; I try to make the sound do some of the formal work. I often think of poetry and think poetically, it’s just that I’ll read a book of poems, a terrific book of poems, and I feel like I could never know how to make something so perfect, like it really takes a special person to produce poetry, and I’m not sure I’m that person.

Recently, however, I’m thinking of writing that is more conceptual, more materially based, and I’m not sure if it’s exactly an essay or something else altogether. I tend to have very flexible views on what genre can be, but sometimes it’s hard to even generously categorize writing when that writing occurs within the so-called “expanded field,” since the real energy in this kind of writing comes from decouple writing from the limitations of the medium or the form.

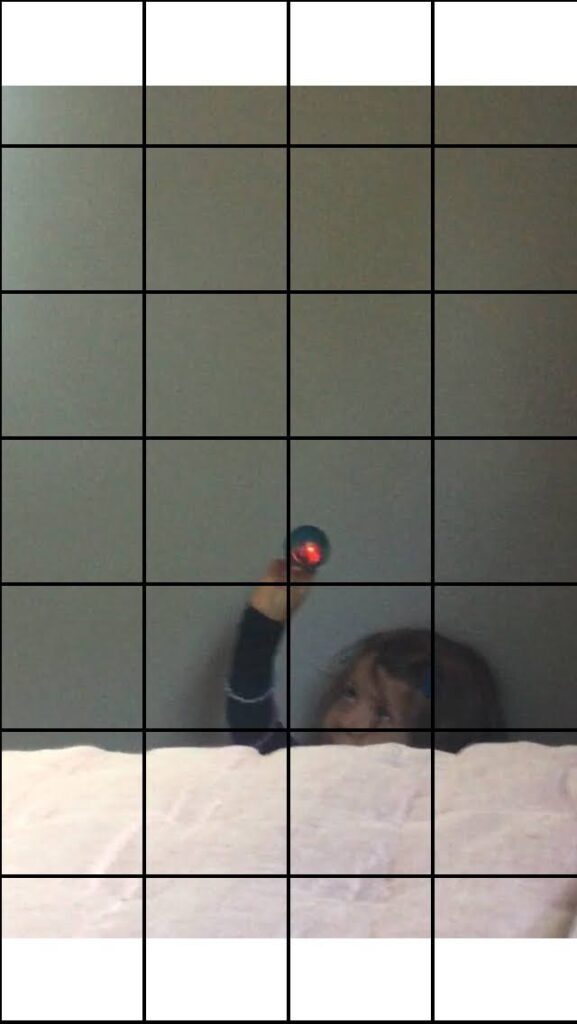

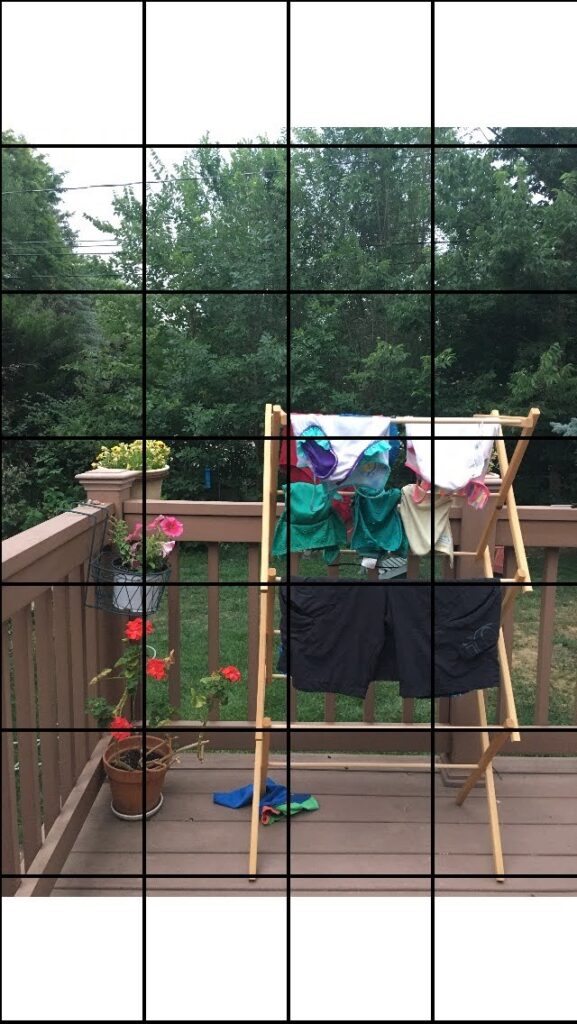

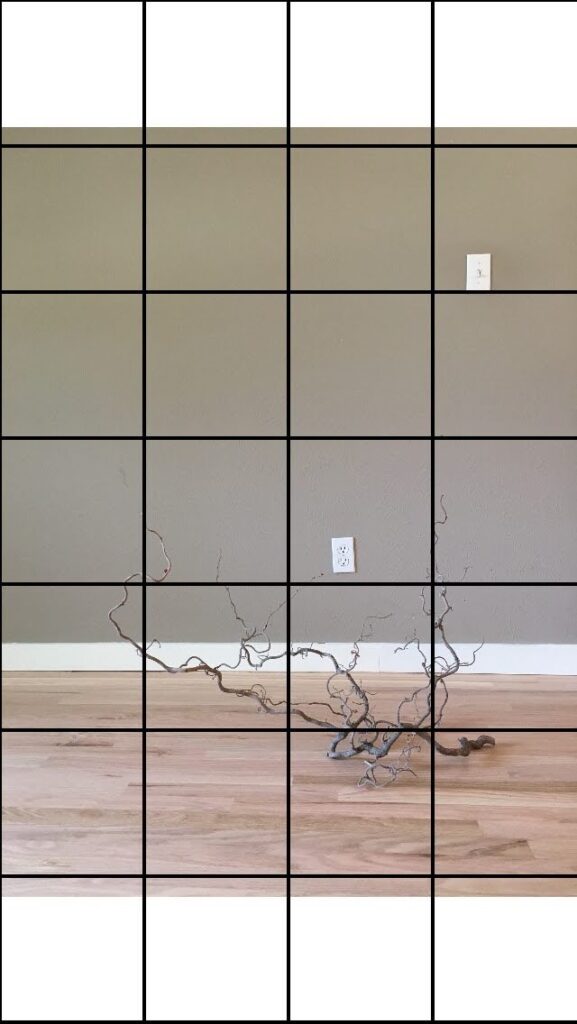

Images by J’Lyn Chapman

I’ve been teaching your book this semester and my students have been particularly attached to the idea of a writing practice with specific parameters, like yours to describe light in To Limn / Lying in. Can you talk a bit about your writing habits? Has structure, in the form of constraint always been part of your process?

No. I need to reintroduce constraint into my practice because it is quite effective. I had followed a constraint earlier in a section of Beastlife called “Our Last Days,” and that’s now a piece of writing I really like. I think the constraint was something like two sentences derived from my daily walk, two sentences derived from the news, two sentences derived from what I was reading, two sentences of poetry. (I should do that again.) What’s tricky, at least for me, is that I have to follow the constraint just to follow it, that is, without any hope that it’s going to become something else. I mean, I always think that’s a possibility, but when I woke up early to describe the light, I didn’t necessarily think it had any purpose beyond putting me in the present moment. There has to be a real surrender to the constraint, the ritual.

Basically, though, I have awful writing habits. I prefer to just coddle my ideas and never risk failing them. I need a lot of accountability, external motivation, and deadlines, and if I can find a way to make that happen I tend to do well. So much of life success is growing in self-awareness so that you can find ways to circumvent yourself.

It’s incredibly freeing to consider any attempt to sit down and write as one “way to circumvent yourself.” I also love your descriptions of writing as a process of ritual surrender, and how this disrupts the myth of the inspired artist that writers are sometimes handed down. Your description also reminds me of what you wrote earlier about making sound “do some of the formal work” in your writing. I’m thinking here about the constraints that get us started, and the later constraints that push the development of a practice into a text. Can you say a bit more about the transitional space or “moment” in the writing of books when you’ve leapt the gap from the daily work of the ritual to the arrival of a different sensibility, or sense of a “project” that arises from the practice? Or maybe this happens more slowly. Do those moments ever happen when you’re “away” from the writing?

Faith is inherent to surrender. Because, on one hand, there’s discipline involved, and that doesn’t always feel good. There’s not necessarily an immediate sense of pleasure or of empirical feedback. It’s so anti-capitalist to engage with something that has no end but itself. And, honestly, I think that if one is an academic, creativity becomes so much a part of how one succeeds professionally that surrender to constraint often feels like wasting time. For me. So faith allows the fall into ritual. But faith is also the means by which we apprehend the unseen, and I do think there’s something magical or metaphysical or spiritual about practice. I believe that sensibility — a constellation of ideas — comes eventually. It’s like you do something and then you have a moment to look at yourself doing it, and you realize that something is happening exactly the way it should happen. I have such strong faith in interconnection and in the soul of everything, even a piece of writing, that I trust that when I engage seriously with a practice, I will eventually apprehend the unseen qualities of it. For me, process involves doing the writing, and then walking away from it to do life. That’s when it tends to make sense and then, inevitably to make un-sense and then to make sense again.

At the heart of To Limn / Lying In is the conversation you’re having with other texts, other writers. While reading your book I’ve also felt an uncanny sense that at certain pinpoints our two books were in conversation — about liminal spaces, light, emergence, visual art, embodiment. Do you think of writing and reading as conversation, inherently? Who are some writers who might not appear by name, but who your books are talking with/to?

Your essay from Bright Archive, “Into the Limen: Where an Old Squirrel Goes to Die,” is quite literally the stuff of my dreams. And of my Instagram obsessions — visual tours of old houses. As well, your book directed me to Claire Pajaczkowska’s “On Stuff and Nonsense,” which has been really integral to a project I’m working on now.

Which is all to say that writing and reading are a conversation. Absolutely. It took me a long time to really start reading, but when I did, my first inclination was to respond to the worlds reading opened by writing into those worlds, to keep them alive or even to add on to them architecturally by writing (for example, lots of Babysitters Club fan fiction). And that’s still how I feel.

I think I am always trying to be in conversation with Renee Gladman. Our writing subjects are very different, but her sentences and ways of thinking about the body in space seemed to have rewired my neurons. I’m constantly referencing her work in class and assigning her books. I think the same goes for W.G. Sebald. I have written about Sebald overtly, but I think it might not be clear now how much of an influence he continues to be. It’s like a whole sensibility that I live with. Renee’s work feels so clean and clear to me, whereas Sebald’s writing is kind of baroque. But I think they have in common a Borgesian world-building. Anyway, I feel very much that Sebald’s death is one of the most tragic literary final stops; I would have really liked to see how his writing and concerns continued to evolve. Virginia Woolf, Lyn Hejinian, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Lisa Robertson. I keep going back to these writers, especially when I feel stuck or when I want to know what to do next.

Your work really does remind me of Renee Gladman’s in the very steady way you both focus us on particular temporal spaces, and your shared ability to stay with individual fleeting moments. It feels so right to describe the lineage of essays, especially, as a kind of giant nesting doll of fan-fiction — each of us writing into the worlds built within worlds built by others. I’m imagining a project, someday, of making a giant web describing each book’s connections to other books. Do you think that being in “conversation” with other writers or writing “back” into that web is ever a way to see forward towards a next project, once one is “finished”?

One of my family’s dinner rituals involves each member telling a story, the only constraint being that it must be a handsome, pretty, or funny story (no scary stories, and, no, I don’t really understand what a handsome story is). I have stopped trying to be original — it’s on the spot — and so I always get the motor running by retelling a story I already know, which eventually morphs into a very different kind of story tailored to my audience. Then my three-year old tells a scatological version of my story. And so we participate in a conversation with other stories that are in conversation with other stories. It’s been so necessary and freeing to do away with the pressures of originality and to just get and keep the story going.

It’s a strategy that is no more or less sophisticated than any of my other creative strategies, honestly. The only difference is that often my conversation will be with visual arts or film rather than solely with other writers. Sometimes it’s not just the conversation that matters but the estrangement that happens when one orients toward different materials.

I really love the image that Derrida casts of reading — just by “looking” at a text, one gets her finger caught in the web of it and also adds a thread to that web, so that looking and making, reading and writing are undifferentiated.

Regarding “webs,” we hear you’re working on a new book about the grid, writing, and devotion. Is the grid also a constraint or parameter? Are you interested in sharing a bit about that project?

I am trying to figure out how to make the grid a constraint. It seems obvious that it is one, right? Not just obvious but that that’s the whole point of the grid. But the grid can also be a window, and so every time I start to work on this project I feel like I’m opening a window, and then all these ideas fly in, and it feels difficult to control. If you have a constraint that comes to mind, I would love to hear it.

I’ve been thinking about grids for a long time, ever since the summer I worked as a technical writer in the military industrial complex and grids were used to align virtual landscapes in helicopter simulators. One night I got to help with this alignment. I felt like a god. I felt like I was producing this giant womb. It was surreal. More recently, though, the grid has returned to me when I had babies. I got interested in Mary Kelly’s Postpartum Document and the grids she uses to represent her son’s language development, as well as the grid produced by her documenting his soiled cloth diapers. I’m pretty sure there’s something essentially shared in these two experiences—mothering, world building, the matrix, womb, eternity. But I also think Kelly’s documentation, a kind of ledger, is just as much a response to boredom as it is to uncertainty. I’m still trying to understand the connections and their implications.

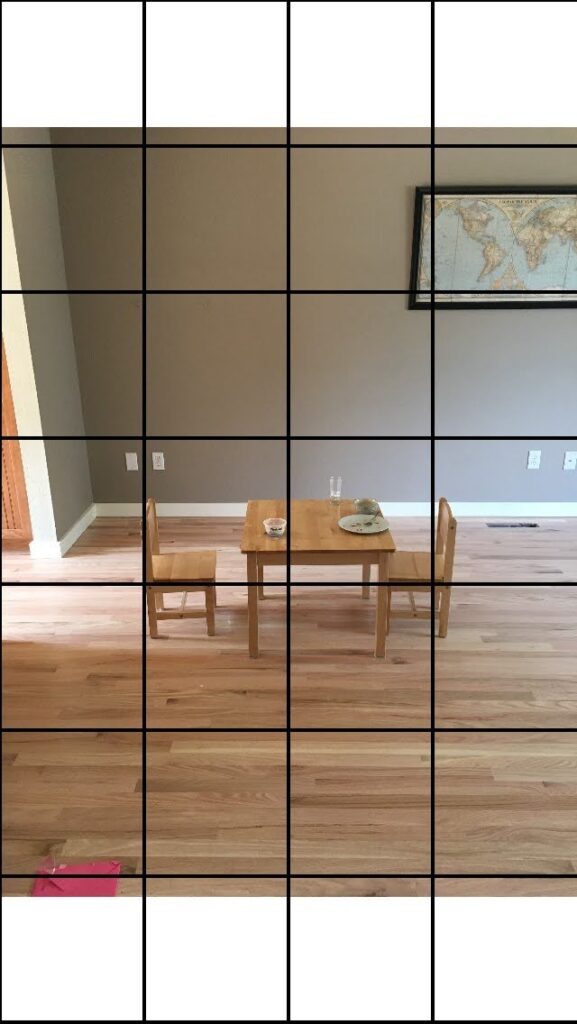

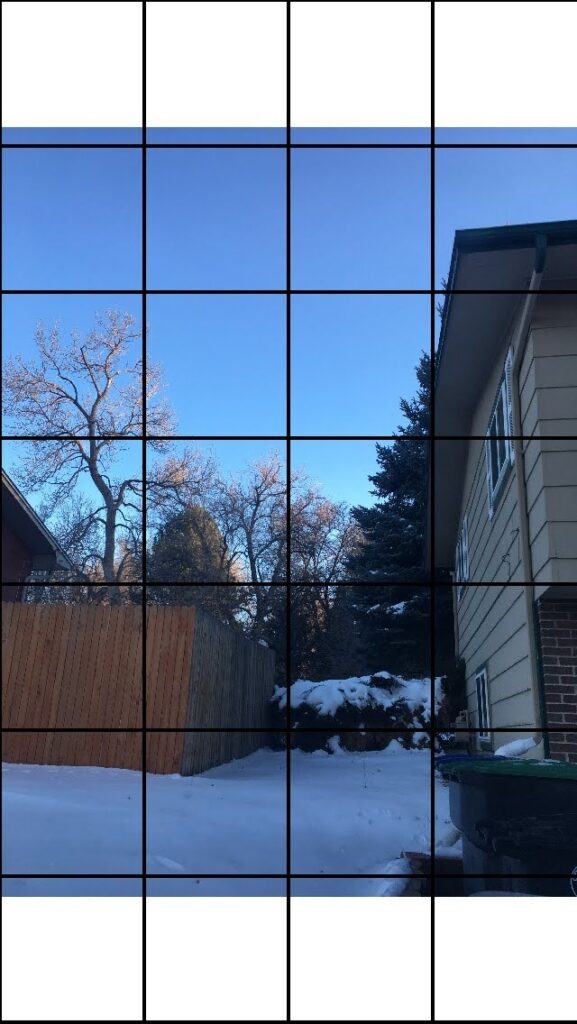

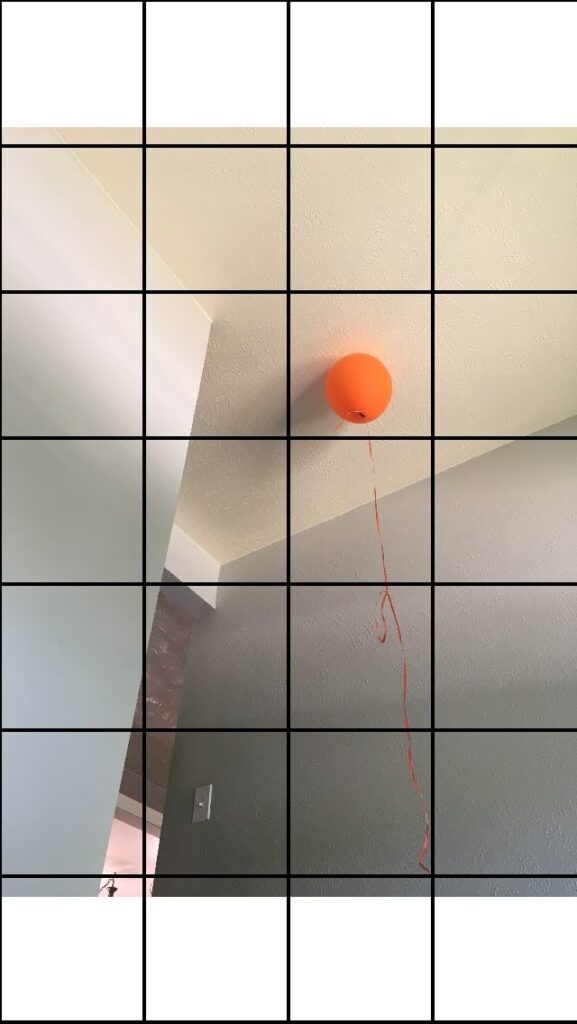

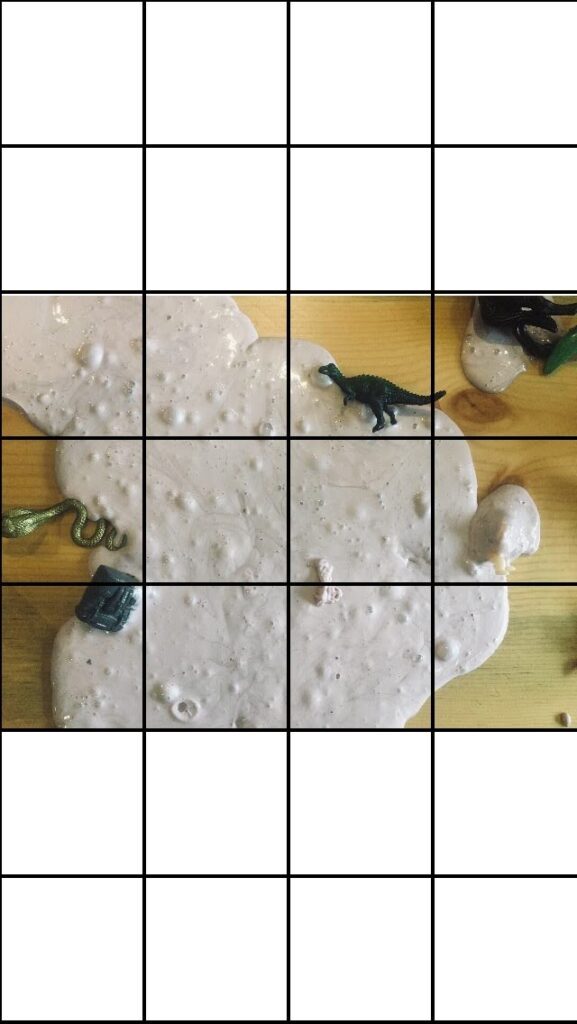

I’d love to read a Chapman book about landscapes, grids, and imagined helicopters. Prompts are always fun to make. My student Jace Lee, a painter and a writer, is making daily work using a grid to paint one square a day using only material found in domestic space — detritus, if you will. I’ll ask her if I can share some examples.

I’m so glad you thought of this. The two places where I’ve spent most of my time these past 12 months are my house and the internet; the latter is very much organized on a grid, and so it makes sense to join the two. But I’m also thinking of Leon Battista Alberti’s veil, a grid of colored string that he used as an aid to perspective in pictorial representation, which is surely how we came to the drawing grid that Jace is using. There is something so immediately poetic in this constraint — perspective, surface, veil, as well as smallness, parceling out, present awareness. I can’t wait to try it.

Grid Prompt inspired by Jace and J’Lyn:

Every day for a week, take one picture of your domestic landscape using this grid filter from Instagram, or this one. Don’t think too much about the photo. The following day, write three sentences about only what is contained / framed / recalled / suggested in three squares of that matrix.

To Limn / Lying In

J’Lyn Chapman

Pank Books

April, 2020

J’Lyn Chapman serves as an Assistant Professor in the Jack Kerouac School at Naropa University. Her book Beastlife was published by Calamari Archive in 2016. She has also published the chapbooks A Thing of Shreds and Patches (Essay Press, 2016) and The Form Our Curiosity Takes (Essay Press, 2015).

Jace Lee (이주은) is a multidisciplinary artist based in Cleveland, Ohio. Her practice is concerned with language and systems of organization, often translating information from one medium to another. Her paintings and drawings exist as a record of human perception to desire order, and the beauty that emerges from this process.

Sarah Minor is the author of Slim Confessions: The Universe as a Spider or Spit (Noemi Press 2021) and Bright Archive (Rescue Press 2020). She is Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at the Cleveland Institute of Art, Video Editor at TriQuarterly Review and the Assistant Director of the Cleveland Drafts Literary Festival.

This post may contain affiliate links.