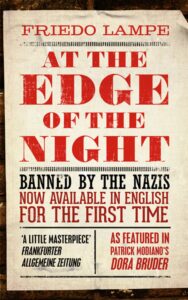

[Hesperus Press; 2019]

Tr. from the German by Simon Beattie

The Hesperus Press edition of Friedo Lampe’s At the Edge of the Night raises the possibility that a lost German classic could well be overshadowed by its author’s extraordinary life story. As translator Simon Beattie recounts, Lampe was a gay disabled writer who somehow managed to survive Nazi Germany, only to die tragically in the final days of the Second World War. A Bremen native who walked with a limp due to a childhood illness, Lampe worked as a librarian and a writer, even as his own books were burned and friends fled into exile. By May 1945, he had lost so much weight that he no longer resembled his identification card photo, and was mistakenly shot by a Soviet patrol. But where does this compelling author and At the Edge of the Night (originally released in 1933) fit within the context of Weimar German literature? Lampe’s publishers have often characterized At the Edge of the Night, which depicts the lives of several Bremen residents over the course of a September evening, as a neglected masterpiece of literary montage. A technique commonly associated with Soviet film directors, montage’s appearance in European and American Modernism carries specific implications: mood over character, multiple voices, the meshing of high- and lowbrow cultures. The disparate narrative threads throughout At the Edge of the Night feel like disjointed images. A young girl has a nightmare about rats and swans, two young men take a ship to Rotterdam, and a pair of boxers face off. But for such an avid book lover as Lampe, this novel’s literary debts feel more nuanced. Intriguingly, Simon Beattie describes this novel as an exemplary work of magical realism. For many readers, magical realism calls to mind a rich Spanish-language and Latin American tradition, from the labyrinthine libraries of Jorge Luis Borges to the matter-of-fact dreamscapes of Gabriel García Marquez. By contrast, German magical realism reflects a collision of intellectual cross currents coursing through Weimar Germany, as the experimental elements of Expressionism gave way to a more objective approach in literature and art. For instance, Thomas Mann’s Mario and the Magician (1929) uses sinister imagery of hypnosis to criticize the rise of Fascism in Europe. Franz Kafka’s Amerika (1927), though posthumously published, also captures elements of the magical realist Zeitgeist when its protagonist joins a mysterious “Nature Theatre” after being cast adrift in New York City. As its title suggests, At the Edge of the Night evokes a world poised on the edge of an extraordinary spectacle, its realist veneer a cover for the rage and sexuality teeming underneath. Examining its portrayal of transformation and violence provides insight into its enduring relevance.

At the Edge of the Night is an absorbing but disorienting experience, depicting a seemingly calm evening punctuated by nightmares and abuse. The line between tranquility and terror is crossed in its opening pages, as a group of children head to a park to see a group of rats. After spotting them, one of the girls screams, horrified by their “nasty look” and “little eyes.” The boys scoff at her fear, but it becomes clear that the park keeper shares her concern, convinced that swimming rats are attacking his beloved swans in the moat. Poring over a newspaper article about a grim New York City overrun by thousands of rats, he writes another unheeded letter to Bremen city officials. A far different scene of artistic whimsy plays out in a local boardinghouse, where a lodger plays Bach on the flute: “Clear, constant, the gentle intervals of the cool, silvery notes floated over the gardens, mixing, melting into the evening air.” How can readers make sense of this imagery, switching between bizarre horror and languorous beauty with the flip of a page? As strange as they seem, these disparate narrative cues resonate with a notable crossroads in Weimar culture. By the mid-1920s, the enduring popularity of Expressionism — teeming with characters who projected their fraught psychological states on their surroundings, with terrifying results — was waning. A steely-eyed realism known as Neue Sachlichkeit [roughly translated as New Objectivity] became the order of the day with its unflinching illustrations of political chaos and postwar trauma. In art, Otto Dix’s portrayals of grotesquely wounded veterans exemplify this trend, but its impact on fiction is more diffuse. Traces of the tension between Expressionism and New Objectivity are apparent in Lampe’s brand of magical realism, a banal night infiltrated by an epic battle between high art and bestial instinct. Even as the flutist imposes Bach’s Baroque elegance on his surroundings, rats are overtaking the city, a prospect that merges Expressionist horror with grim resignation about the dark aspect of human nature. As the night unfolds, many inhabitants of the city engage in petty power struggles and cruelty, bearing considerable resemblance to vicious rodents. This theme closely resembles the work of Lampe’s better-known contemporary, Nobel laureate Hermann Hesse, a longtime admirer of this novel. The protagonist of Hesse’s Steppenwolf finds himself trapped between spiritual aspirations and the savageness of a wolf. But where Hesse focuses on self-actualization — rendering him a demigod of the 1960s counterculture movement — Lampe’s depiction of this conflict and its cumulative effects on a cast of characters feels more unsettling. With the boundaries between human and animal unclear, the slightest shift could tilt this pedestrian world off its axis. Anni, the older sister of the young girl who screams at the rats, is horrified that her husband might come home intoxicated. When he arrives one night pretending to be drunk, she becomes a picture of fear, convinced she is “completely alone, abandoned with this strange man, in a strange house, in the night.” When he explains the joke, she begs him never to “change like that again,” and domestic bliss is restored. This odd exchange reveals much about the novel’s preoccupation with transformation. Lampe’s magical realism is a delicate balancing act of competing elements, a predator lying in wait for its characters to throw themselves off-kilter.

A persistent threat of danger lurking beneath the mundane renders Lampe’s narrative voice unique even among his most avant-garde contemporaries. At its loftiest, At the Edge of the Night can feel abstract and detached, offering little hint of how its copies ended up in Nazi book bonfires. But as the night pulls these characters into an unsteady embrace, it becomes clear that the dividing line between the real and the surreal is their own compulsion toward violence and sexual power struggles. Consuming fear about the loss of control ups the stakes. Nowhere is this sinister dynamic more apparent than in the narrative thread about Oskar and Anton, two students traveling from Bremen to Rotterdam by ship. Once aboard, they recognize the steward as their former university classmate, Fritz Bauer. Taken aback by his aloofness, they soon discover his disturbing sadomasochistic relationship with the ship’s captain. Anton, the more sympathetic of the pair, tries to reason with Fritz. Realizing that the captain enjoys torturing and has “ruined” him, Fritz seems helpless, insisting that he will “only drift back again” if he escapes. Yet in the midst of Anton’s attempted intervention, he turns vicious, revealing how quickly the victim transforms into victimizer. When the captain’s dog attacks him suddenly, “thrashing about and snarling greedily,” he kills it with a cleaver. This intense portrayal of a dog-eat-dog world with homoerotic overtones accounts for why this novel was only re-released in expurgated versions throughout the twentieth century. But it is also crucial for understanding Lampe’s legacy. His magical realism embodies a rich and complex combination of influences. For example, this encounter between Anton and Fritz owes as much to nineteenth-century German theater as to film techniques. Similar to Fritz, the protagonists of dramatist Georg Büchner’s plays (a known presence on Lampe’s extensive bookshelf) walk a fine line between exploitation and rage, capable of self-degradation and murder in equal parts. Rather than an alternate world with supernatural creatures, this parallel universe offers a troubling prospect. Initially true to Expressionist credos, the characters’ deepest psychological motives are laid bare in public, but their seemingly tranquil surroundings do not echo their torment. Instead, the consequences of their dark actions can be humiliating. In the novel’s final pages, Fritz admits to Anton that “I’m past saving,” choosing to stay with the captain. A local boxing match draws similar parallels between sexuality and violence, as a boxer’s one-sided attraction to his opponent erupts into ferocity, leaving the object of his affections battered and bruised. Despite its vast array of literary and cinematic allusions, At the Edge of the Night entertains the possibility that the most base cruelty and desires may still win out: a rat can always kill a swan. Though bleak, the conclusion seems fitting from a man trying to survive in an increasingly authoritarian society. Lampe despaired upon this novel’s publication that it was “born into a regime where it could not breathe.” Shining new light into the hollows of a dark September evening in Bremen, this translation provides a talented but widely forgotten author some much-needed breathing room.

Emily Hershman received a Ph.D. in English at the University of Notre Dame. Her writing has appeared in the James Joyce Quarterly and elsewhere.

This post may contain affiliate links.