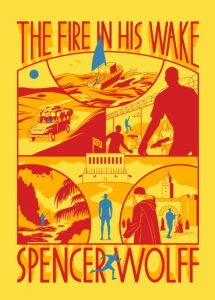

[McSweeney’s; 2020]

There are plenty of books available to readers to remind them of the presence of violence around borders and the movement of people from one country to another. Articles, TV charlatans, and politicians can be found discussing border policy weekly as a source of threat, violence, and destruction, or at times a site of potential for progress and communal solutions. The myth-making that goes into talking about border narratives is an industry in itself — whether it is the Rio Grande or the Mediterranean or the 38th parallel of Korea makes little difference. From the confusion of policy, to confusion of actors from states to huge NGOs to small local nonprofits, and to dire reports of violence or destabilization, a very important reality is lost. Real human lives with real human stories are suffering and dying.

Spencer Wolff’s book, The Fire in His Wake, begins with an official UN refugee interview whose questions are distant and yet repeated throughout the story. The reader is immediately confronted with the forcefulness of a supposedly human rights process. Each interview begins with the same demand, no matter how many times the same person has been asked, “Please talk about your life story in a manner that is open and above all honest. Everything you say here is entirely confidential.” And, every interviewing officer has a set of parameters to keep in mind, “Does the harm feared by the applicant relate to one or more of the grounds of the 1951 convention or the 1967 protocol: race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group.”

The narrative moves to the story of a young Congolese man Ares, who is ethnically Rwandan. His father is a locksmith and community figure who brings together the town around an exercise of prophetic chance. The winner of a race is given the chance to find a key and open one of three boxes. Ares opens the one with planes inside, at which point his father declares, “it seems our great country is too small for my son! Let us wish him success in his travels.” This is the story’s first ominous hint of the long journey ahead. Shortly after, his family is attacked for being Rwandan and murdered viciously in front of him. He is mysteriously saved and sent on a long trip down river to a town where he will stay six years. There he meets his next companion, Paul the Cameroonian, a traveling merchant, full of wisdom and sayings, who eventually takes Ares with him to Cameroon. From there, Ares will take a long ride on to the city of Rabat in Morocco and hope to resettle in Europe.

Mobutu, dictator of the Congo, haunts Ares’ journey and provides the title of this book. The dictator is described as “the all-powerful warrior, who goes from conquest to conquest, leaving only fire in his wake.” Ares will travel the same route as Mobutu, whose final resting place is in Morocco but the fire will be different. The powerful elite shadow much of the story with faint whispers of the even more ominous European and corporate powers that have caused so much of the continued instability. The real narrative focus, however, is on characters without much power. They often communicate through short proverbs as much as shared experiences to make sense of their lives. For the reader, the work comes across as an incredibly expansive and organic scripture. The proverbs equally parse out the joy and harshness in reality with an overtone of conspiratorial comradeship. Paul, for example, reminds Ares, “to be rich is good, but to still be alive the next year is worth even more.” Or later in the story as violence mounts, the reader is told, “the prayers of the chicken do not influence the falcon.” Their use is so frequent that they become an obvious foil to the more officious language of the white UN characters, which makes them seem even more detached.

Another personal story begins to unfold. Simon, a young, blond, white American is the son of a diplomat. Simon dreams of the top bureaucratic job in a glass office in Geneva away from the harsh reality of Rabat or any field office. However, his job for now is to work with the field staff to help with the resettlement and refugee status of applicants at the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). At every turn, his failure to see the humanity of refugees and asylum seekers is clear. One of his first descriptions of refugees is as supplicants who, “hold out their hand and we put things in it.” He is unable to see the complexity of the UNHCR’s position or the entangled reality of Morocco being a part of Africa and yet being vehemently racist towards black Africans. He embodies a characteristically American selfishness with a lack of curiosity.

Simon and Ares are bent on a collision course but first the stories of the two must develop. Simon becomes a little more human and compassionate. His relationships to his roommates, coworkers, and eventual girlfriend, Nadia, awaken him. Ares, more and more affected by the powers of neocolonialism, wrestles with utter despair, at one point stating a fear, “My file. I think my file has replaced me. My face is made of paper.” He is stuck in a system of violence and disregard that leaves him to wonder, “No, I am not some monster, he told himself. Not yet. But the violence seemed to have been etched into his face with a knife.” As he wrestles with hard questions, he forms a deeper connection to his fellow refugees.

Wolff paints the UN itself as another character through the use of faux documentation. The reader is exposed to what an interview process looks like for someone attempting to get refugee status or to be resettled. Over and over again, the refugees must share their stories of incredible hardship and trauma. They must relive tragedy to prove their stories. It quickly becomes clear though that the arrangement cannot lead to anything other than adversarial roles. On the one hand, the supposed refugee is lying or selling their story to others. On the other hand, the UNHCR is a pointless bureaucracy that does nothing. It is no surprise that entrance into Europe is managed exclusively by white Europeans, all of whom are incredibly officious and take to heart the importance of “mandate” and “protocol.” The UN bureaucrats are of course stuck in the position of gatekeeping for European countries but unlike the refugees, they are not stuck in the position of being bludgeoned by Moroccan police or having stones thrown at them by children or having money stolen by employers or being constantly dropped off on the border between Morocco and Algeria. The spectrum of opinions within the UN is elaborated, on one side, by Baptiste, a Nigerian colleague of Simon, who says, “It’s not up to us. I have a mandate that is given to me. If I do not fulfill that mandate, then I will be removed, and someone else, who will carry out the mandate, will take my place.” On the other side, Anna-Heintz, a European colleague, is unequivocal in the importance of the mandate and obtusely quotes Wittgenstein to remind Simon that they can never understand other people’s experiences or culture. What Wolff makes clear through his storytelling is how impactful the presence or absence of power is in a character’s creation and interpretation of their narrative.

Wolff does an incredible job of painting how two people can have utterly different visions of life and utterly different experiences of a place by completely changing perspectives from Simon to Ares and back again. We see the visceral incapacity of Simon to focus on the reality right in front of him; instead, we see him banter easily with colleagues at the many parties the various NGO folks attend. Whereas with Ares, we begin to see the formation of his righteous anger at the doublespeak and gatekeeping of the UN. He is in a dire situation as a refugee, or unrecognized citizen, and yet still exhibits an incredible amount of will to go on. Whereas the characters Simon meets are constantly challenging him to grow up and deepen his awareness, the characters in Ares’ life are either in solidarity with him, sharing the same hardships and yet making meaning of them, or the officers of the state who wield truncheons and fists.

Simon finds his own foil not in Ares, for there is too much red tape and misunderstanding between the two, but in a flatmate he didn’t really want, Kinani, another refugee from the Congo who is invited by the two French interns Simon lives with. It is clear the two don’t like each other from the get-go. But one drunken night, Kinani’s story comes out: he is the son of a Congolese diplomat who worked for Mobutu. Simon spends so much of his time on the surface of issues that he cannot see with clarity the humanity right in front of him. Over glasses of Johnnie Walker, Kinani pushes Simon to acknowledge a deeper reality:

“A refugee is the name we give to an idea that frightens us,” Kinani said, staring severely at Simon, “so we don’t have to call it by its true name.”

“Which is?” Simon stuttered . . .

“A refugee is just a person,” he replied quietly. “And that’s what scares us, because a person is like us. In our minds, becoming a refugee is something that happens to other people . . . We give them these names to convince ourselves that these are things that happen to someone else. That’s what I thought too, until it happened to me. Then I became something that happens to someone else.”

It dawns on Simon for the first time in the book that a refugee is a human.

Near the end, the refugee community has organized to protest and vent their rage outside the UNHCR building. The power available to them is represented by their voices and the stones they are willing to hurl at the property. The Moroccan security forces that defend the UNHCR have guns and a state behind them. This is the final image of the power aligned against this suffering community. While the UN employees remain safe, though frightened, the refugee protestors are beaten savagely. The character’s scale of power is so deeply connected to their ability to recognize humanity. Simon has power and little sense of humanity. Ares has little power but is open and honest. The UN plays the card of innocent middleman but their security is violent and state-sanctioned. From the perspective of Ares and his fellow refugees, it is hard to discern a difference between the security’s violence and instability from that which caused their refugee journey in the first place. They are left to acknowledge the refugee’s place in this world is like the rope in a giant game of tug-of-war.

Wolff’s capable storytelling illuminates the complexity of the refugee situation in Morocco, not by discussing the minutiae of policy or politics, but by lifting up the story of two genuine human beings who cannot actually relate to one another because of all that exists in the self-interest of states, colonialism, and self-protective bureaucracies. There is no real moment when Simon and Ares understand each other or when anything is truly resolved. The end of the story leaves us with Simon in love with Nadia, with her own complicated status as an “other” in Morocco, and Ares blending into a mystical experience of swimming the Mediterranean with the spirits of other refugees, while disappearing in the eyes of most of the white characters: “The whole sea, from horizon to horizon, was seeded with silvery swimmers stroking side by his side. Thousands of African souls stroking through those hostile waters, so many they submerged the waters beneath a wet silvery stream flooding north towards deliverance.”

The amazing scale of the book and depth of humanity will at times enrage the reader as much as encourage. The gargantuan complexity of the human issues at the novel’s heart is a good reminder of the importance of storytelling that is honored and not coerced, believed and not picked apart.

Alexander Barton is an Episcopal Priest in Lorain, Ohio where he spends most of his time processing the effects of late-capitalism with his parishioners. He teaches classes about the intersections of race, politics, and theology. He loves James Baldwin and Toni Morrison and is always looking to force others to read them.

This post may contain affiliate links.