The following is from the latest issue of the Full Stop Quarterly. You can purchase the issue here or subscribe at our Patreon page.

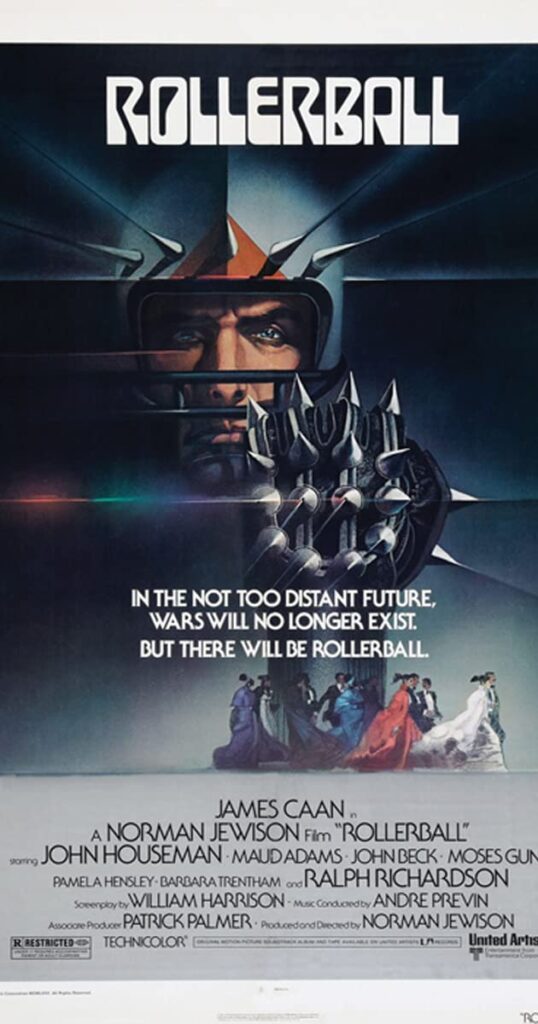

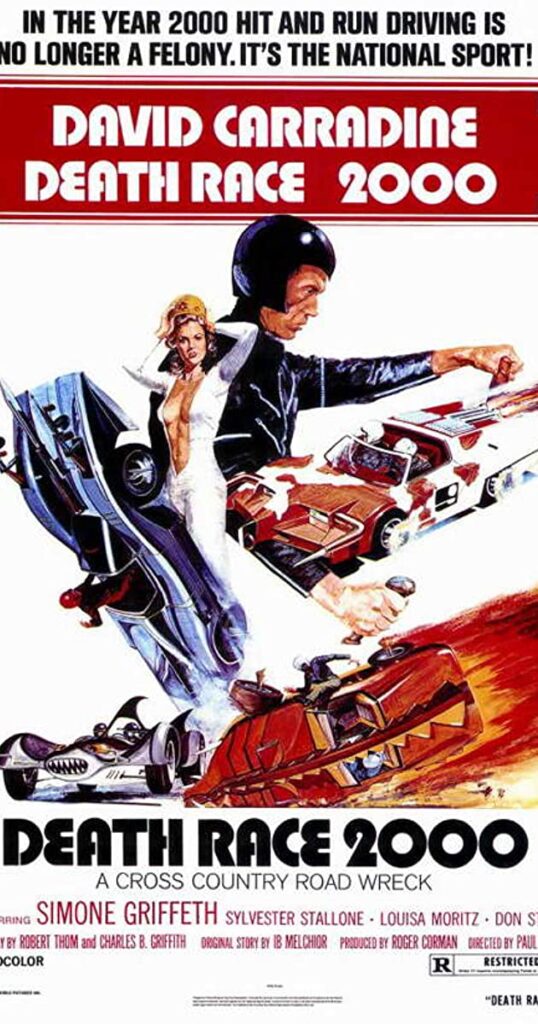

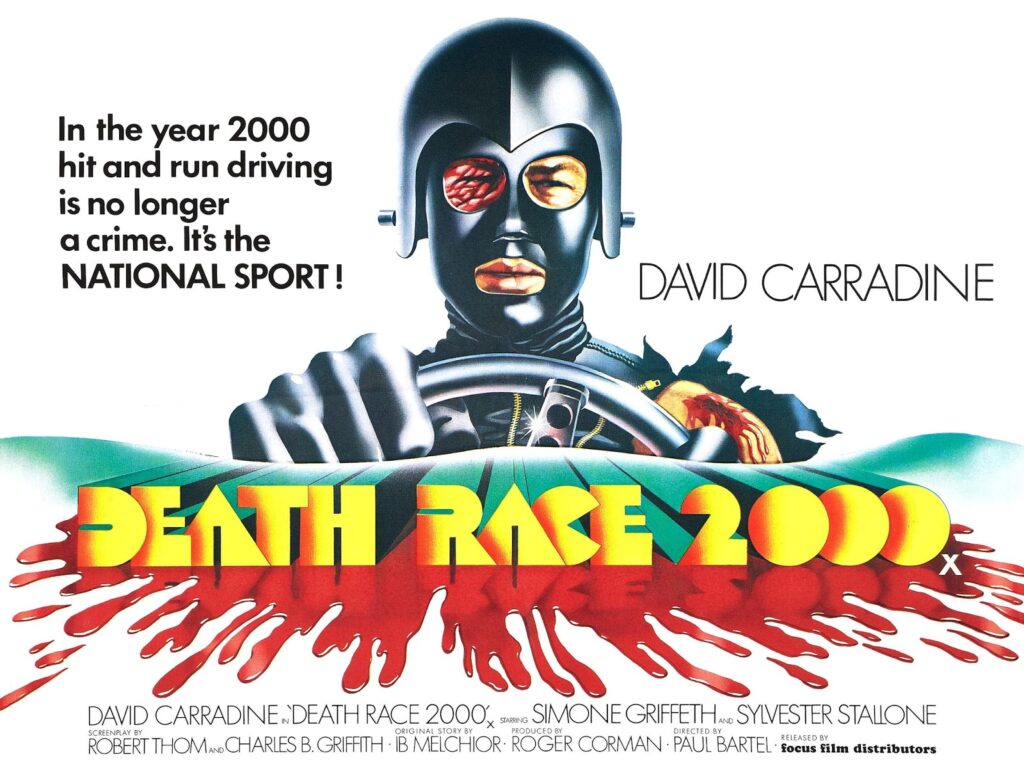

In June 1975, two film reviews ran in the New York Times, twenty days apart. Both were negative. The reviewers of Rollerball and Death Race 2000 criticized the films for being short in satire and substantive storytelling. The former film, the writer noted, “spends far too much time on the graphic details of the various Rollerball contests to mean for us to find them nothing more than a melodramatic swindle,” while Death Race 2000 “reveals itself to have nothing to say beyond the superficial about government or rebellion. And in the absence of such a statement, it becomes what it seems to have mocked—a spectacle glorifying the car is an instrument of violence.”

But forty-five years on, these sports science fiction films which presented depictions of dystopian futures retroactively offer insights into political concerns pervading the 1970s—a decade characterized by crises in oil and energy, global stagflation (a coterminous stagnation and inflation), frivolous wars, and global political revolutions. None of which, of course, can be understood as separated from one another.

With overlapping trends, the films imagined two different futures at this particular historical conjuncture. Rollerball envisioned a reality where the corporate realm completely supplanted the nation-state order, whereas Death Race 2000 speculated about a unipolar dominance of the US with corporate hegemony and the suspension of internal democracy. Both, however, used sport as a medium to think through both the political limitations of the present conjuncture and the ability of labor to reassert a power in shaping that ill-defined future.

Although The New York Times and several other highbrow media outlets at the time dismissed the two films for gratuitous displays of violence and campy features, revisiting them as responses to the oil, energy, and capital crises of the 1970s might offer new ways of contextualizing a present reality where things seem to be inverted—gas prices are at an all-time low and hyper-commercial sport has been on pause for some time [as of this writing]—but private corporate capital still reigns supreme. As they both eyed a future that was yet to be written, they may have been early entrants into diagnosing that dreadful feeling that accompanies the unbeatable supremacy of capitalism.

“The Futility of Individual Effort”: Rollerball and the Oil Shock

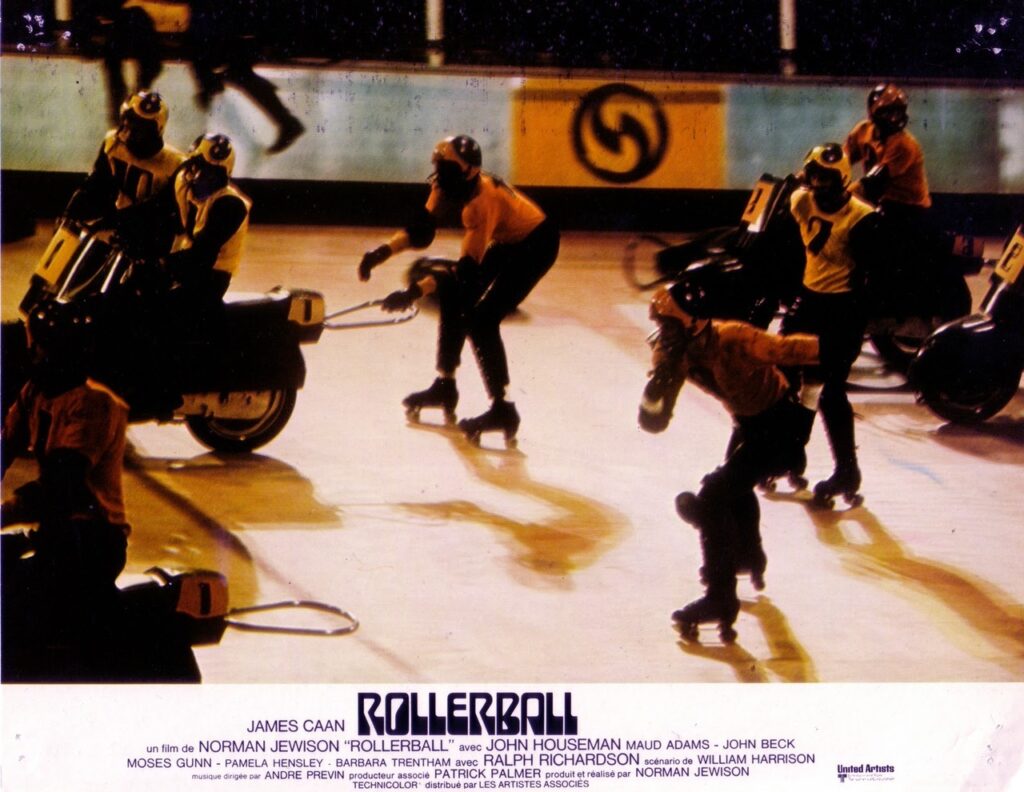

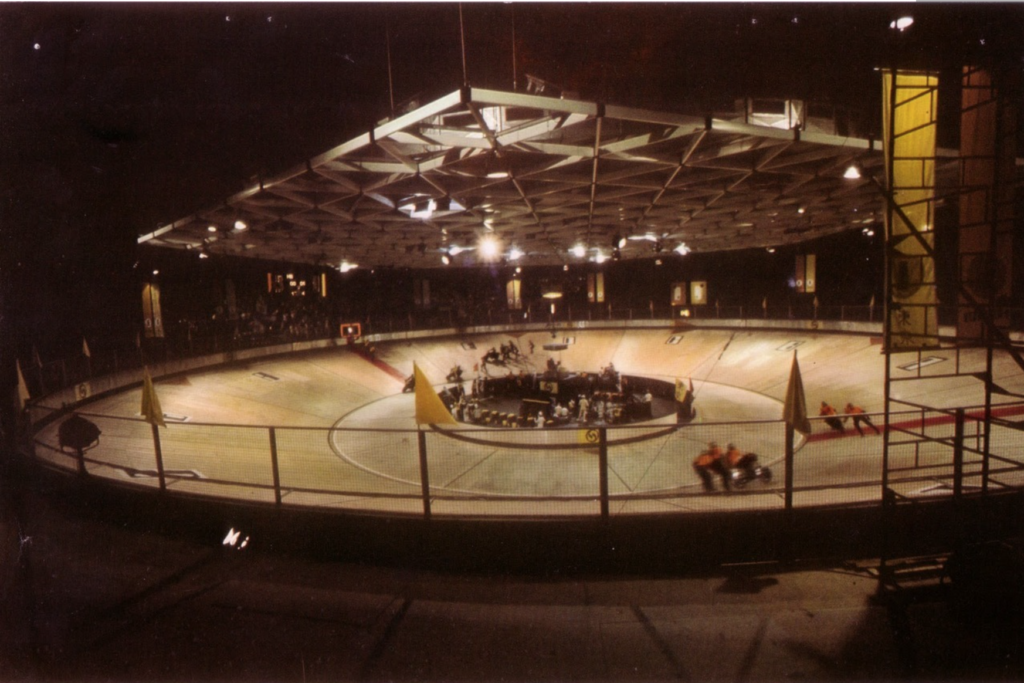

Rollerball (directed and produced by Norman Jewison) begins in a velodrome with dramatic organ music playing in the background just moments preceding a game between Houston and Madrid. Sitting in the arena’s box seats, high powered men in suits look on, ready to consume the game. The team is announced and Jonathan E. (James Caan)—a legend in the sport—gets his special moment in the spotlight. Then, the corporate anthem is played.

We’re never explicitly told the rules of Rollerball, and that’s because they are changing all of the time, at the behest of the owners. But two teams of about ten players begin the game. Roller skaters and motorcyclists move around the rink in a uniform direction. A heavy steel ball is shot in the reverse direction and goes around the velodrome until someone captures the projectile, positioning his team to be on offense. The team with the ball then proceeds to go in circles and try to score by placing the ball in the opponents’ goal, which is also at the top of the velodrome. There are referees who issue penalties for aggressive practice, but from the get-go we clearly see this is a violent game.

The short story “Roller Ball Murder,” by William Harrison, upon which the movie is based, sheds a little more light into some of the specifics that structure this world. Corporations have replaced nationalism and nation-based sporting events (e.g., the World Cup). Rollerball is run by corporate city-states and executives from energy companies, and the violent spectacle of sport clearly serves as a cultural object that allows this global order to cohere.

In this first competition, Jonathan leads his orange-suited team to victory alongside scores of players being brought in to nurse injuries. As the team celebrates in the locker room, Mr. Bartholomew (John Houseman), the head of the Energy Corporation, congratulates them. He also notes that a special program about the career and life of Jonathan will run on multivision and instructs the star athlete to meet him regarding the program the following day.

In the subsequent scene Mr. Bartholomew tells Jonathan he should retire. He doesn’t explain why, but rambles on about the current state of things:

You know how a game serves us. It’s a definite social purpose. Nations are bankrupt. Gone. None of that tribal warfare anymore. Even the corporate wars are a thing of the past. Now we have the majors and their executives. Transport, food, communication, housing, luxury, energy. A few of us making decisions on a global basis for the common good.

Many of the details of the rules of society are not clearly articulated throughout Rollerball, with good reason: Corporate control extends beyond finance—but seeps into the realms of knowledge production. Like Jonathan, the viewers should not be troubled with these gaps in plot development, as a select few are “making decisions on a global basis for the common good.”

It is in this context that Mr. Bartholomew tells Jonathan the only thing the game and the executive class has asked of anyone is “not to interfere with management decisions.”

There’s a lot to unpack and contextualize in the setting of the story and film itself, which is rooted in political economic shifts that occurred throughout the twentieth century between contestations to US supremacy and the rise of corporate power. Timothy Mitchell outlines these shifts in the longue durée in his book Carbon Democracy, which describes the geopolitical factors influencing a transition from a coal-fueled economy to an oil-fueled economy.

Following the second World War, forty-four Allied Nations set out to form a new global financial order through the Bretton Woods Agreement. They built exclusive institutions like the IMF and what would become the World Bank and pegged global exchange rates to gold. As the US controlled the majority of the world’s gold and oil at the time, this meant that the US dollar, oil production, and geopolitical power were closely connected.

This global hegemony was threatened shortly after the agreement, when several Arab countries ramped up oil production. A powerful Middle Eastern bloc began to undermine US dominance by forming the Organization of Petroleum Export Countries (OPEC). Made up of mostly Arab countries, by the 1970s OPEC’s membership accounted for more than half of the world’s oil. And with their newfound power, they threatened to put an embargo on oil from the US if they continued to meddle in Middle Eastern politics.

Private capital interests from private US firms, fearing a new world economic order, urged President Nixon to back out of the Bretton Woods Agreement, and in 1971 he took the US dollar off the gold standard. Corporate power, riding the perceived demise of the role of the state and rise of privatization, began expanding its sphere of influence.

With the US still rejecting Palestinian self-determination, OPEC proclaimed an oil embargo in 1973, allowing the price of oil to climb 400 percent and sending the US into a recession. Thus, two years on, Rollerball seemed to be imagining the future of a new era. It predicted that the entities that would win out from this energy crisis were the oil conglomerates—private capital firms in major financial urban centers who thrived on fossil fuel production (spoiler: In this regard, Rollerball was right).

Thus, when Mr. Bartholomew notes that the executive class only asks people “not to interfere with management decisions,” we understand that a critique levied against private corporations—from low-waged workers to sports icons generating revenue—would be met with severe blowback. The corporations, in this world, have bankrupted the nations.

Yet, Jonathan does not listen. He refuses to retire and he competes in the next game against Tokyo, against the advice of his confidants. Because of this interference, the corporate executives change the rules and rid the game of penalties. In a spectacularly violent game against Tokyo, Jonathan again leads his team to victory. However, Moonpie (John Beck), a key player and good friend, is left in a vegetative state while several others suffer fatalities.

Mr. Bartholomew then holds a virtual meeting with other corporate executives where he states the collective reason for issuing Jonathan’s retirement: “The game was created to demonstrate the futility of individual effort.” A star player such as Jonathan defeats the meaning of the game, and thus he must lose. Mr. Bartholomew asks for support in changing the rules of the final game in a plea to lead to Jonathan’s demise. In the final against New York, they announce that there will be no penalties and no time limit. Essentially, the last man standing—or rather, living—will win.

Meanwhile, Jonathan travels to Geneva to use the world’s central supercomputer “Zero” and learn ‘how corporations make their decisions.’ But when Jonathan poses the question to the supercomputer it eventually only spits out backtalk: “Corporate decisions are made by corporate executives. Corporate executives make corporate decisions. Knowledge converts to power. Energy equals genius. Power equals knowledge. Genius is Energy.”

Just as viewers feel there are so many contextual questions to be answered, we now understand Jonathan’s seemingly one-dimensional response to all of the news he receives throughout the film: There is little that can be answered when corporations, powered by influence over the energy sector, control knowledge as well.

The final game against New York quickly escalates into gladiatorial violence. Some brutal and gory sequences allow Jonathan to emerge as the lone player on the track, killing several opponents, and scoring the game’s only point. At first the spectators are silent, and then they loudly chant his name as Mr. Bartholomew storms out. The dramatic organ music that introduced the film plays again before an abrupt shift to the closing credits.

Despite the normative narrative of a star player leading his team to victory, the film hardly ends on an upbeat note. On the one hand, Jonathan has, so far, defied constraints placed upon him and the game enforced by the reigning corporate order. But with his teammates dead and gratuitous violence in his path, the idea of individual victory still feels futile. Capital, with the corporation as its vehicle, wins out in this post nation-state global order. And sport provides an ideological structure through which fans may feel they are a part of something else, but which actually serves to strengthen the reality of capital’s reign.

Athletes Embodying Capital’s Contradictions

This type of tension is precisely why a depiction of capitalist sport is an ideal vehicle to understand the coterminous possibilities and limitations for workers of all stripes within a late capitalist structure dominated by corporate capital. Athletes are Janus-faced figures, at once Promethean in their abilities, but relatable and normal subjects in their highly constrained sphere of action.

There is a material history at work here as well. Not only did modern sport coincide with the development of industrial capitalism in the eighteenth century, but it was an integral part of its development. Tony Collins makes this argument in Sport in Capitalist Society by exploring the ways sport was an arena governed by moral imperatives and amateur ideals through which aristocratic classes could institute forms of discipline to secure their power. Ideas about “fair play” were central to capitalism’s promise of liberty and freedom. So long as athletes played by the “rules of the game,” we would celebrate their achievements. However, as seen in Rollerball these rules are often arbitrary and can be changed to serve a small elite class.

Capitalist labor relations are full of contradictions, and within sport, a complicated embedded tension is that particularly gifted athletes often yield a special kind of power through their excellence. While workers in most sectors usually gain strength from their collective power to stop working—often in the form of an organized strike—star athletes can make statements precisely by excelling through their work.

The most iconic example in sports history came a mere seven years before the film’s release. At the 1968 Olympics, two African-American athletes, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, raised their fists in the air atop the Olympic podium to protest racial and economic inequality. The Mexico City games were already mired in controversy. The host city saw an onset of political activism and subsequent violent suppression, many athletes considered boycotting the games due to segregationist and racist policies around the world, and rumblings of protest actions by athletes were met with threats from the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and other governing bodies. Not only were Smith and Carlos sent home from the games, the IOC forced the two athletes to return their medals thereafter.

In being so successful through the rules of the game, like Jonathan, they had come to defy them, and the rules were changed to work against them.

No Holds Barred in Death Race 2000

While different in tone, style, budget, and conjecture, Death Race 2000 also situates a sporting protagonist in a capitalist landscape run by grotesquely powerful leaders that prop up the virtues of violence through sporting ideology.

Prophetically, this film is set about twenty years after the “World Crash of ‘79” (the year in which the second oil price shock hit, resulting in widespread petrol-economic panic) on the twentieth edition of the Transcontinental Road Race. The sporting event is a three-day competition in which drivers and their navigators race across the country and get points for killing pedestrians.

Unlike Rollerball, some of the other competitors get a few moments in the spotlight: cowgirl Calamity Jane (Mary Woronov), neo-Nazi Maltida the Hun (Roberta Collins), Roman gladiator Nero the Hero (Martin Kove), and Chicago gangster and prior runner-up Machine Gun Joe Viterbo (Sylvester Stallone). But the protagonist is Frankenstein (David Carradine). Like Jonathan, Frankenstein is the iconic sporting hero and greatest racer of all time. He has a close relationship with Mr. President, and dressed in all black with a mask covering supposedly brutal scarring, he is the clear favorite to win.

Aside from the names and personas, the cars themselves allude to a cartoonish mockery of the event. They are the kind of vehicles that might have been options in a 1990s racing video game. While Machine Gun Joe’s is a slick black muscle car with some weapons popping out of the front, Frankenstein drives something that most closely resembles a crocodile. Painted green scales, with spikes from hood to trunk and white teeth shooting forward from beneath the front of the car render our masked hero all the more difficult to take seriously.

But the fans, and the president, are clearly unshaken by the cartoonish aesthetics and ready to watch the event. To announce the start of the race, Mr. President gives a speech from his Summer Palace:

I have made the united provinces in America the greatest power in the universe. I have also given you the most popular sporting event in the history of mankind. The Transcontinental Road Race, which upholds the American tradition of no holds barred.

In contrast to the complete demise of the nation-state in Rollerball, in some ways Death Race 2000 (produced by Roger Corman, directed by Paul Bartel) more accurately saw the way the state would restructure its relation to capital to see the rise of elite vanguard political parties—and indeed the American imperative to allow capitalism to persist by any means necessary.

The particular reference to the transcontinental railroad—a coal-powered product of the industrial revolution—also makes clear the new petroleum-driven economic order that was characterized by this eventual transition to an oil-driven, rather than coal driven, economy. Mitchell notes that while the coal economy often dictated brutal working conditions, it also enabled workers a kind of space through which they could organize for better wages and working conditions. The transition to a fossil-fueled economy, however, meant that the movement of the oil commodity was more easily controlled by a smaller management class and labor was more dispersed. Further, the transition from coal to oil also meant a rise in the power of the auto industry. While the railroad had been an iconic symbol of American innovation in the past, it was now cars—often big and fuel-inefficient—that demonstrated US power.

In 1973, when oil prices doubled and stock was in short supply, Americans were only allowed to fill up their vehicles on certain days. Thus, the spectacular, brutal event showcasing the oil, car, and energy economy in Death Race 2000 made racers and the cars the perfect vehicles for a 1975 film to showcase the American culture of “no holds barred.”

Alongside the Transcontinental Road Race, a resistance group is attempting to foment a revolution by sabotaging the event. Led by an older woman, Thomasina Paine (Harriet Medin), they plan to kill racers and the president. After she publicly declares war over various media outlets, Frankenstein appears calm. His navigator, Annie (Simone Griffeth), whose undercover role is to covertly lead Frankenstein into a trap where the group will take him hostage and use him as leverage to meet with Mr. President, is puzzled by his composure.

Frankenstein learns of her plans and then reveals to Annie that Frankensteins are multiple; he is one of many wards of the state who was raised in a government center and trained to race in the identity, and if he dies, he will be secretly replaced. This way Frankenstein—an agent of the state and friend to Mr. President—appears to be indestructible and unbeatable.

Again, like Jonathan E., we see the manufacture of the “star player.” While he is seen to embody an exceptional spirit for the public to revere, his individual character is not supposed to shine through. In fact, his very state-sanctioned growth situates him as a simultaneously singular and disposable figure.

However, this particular Frankenstein, more consciously so than Jonathan E., is disobedient. He tells Annie he was also scheming to rebel and had his own plan to kill Mr. President after winning the race by shaking his hand with a prosthetic bomb in his right hand. But right after this reveal Machine Gun Joe launches an attack against the two and Annie takes the prosthetic bomb in his car to kill their final competitor.

With Frankenstein as the de facto winner, but with the prosthetic bomb gone, the two alter course. Annie dresses up in Frankenstein’s costume wielding a knife, with the intent to stab Mr. President. However, she does so without informing her resistance group. Thus, as Thomasina Paine thinks she has failed to take Frankenstein hostage, she shoots Annie. With pandemonium and confusion around the awards stage, Frankenstein drives his car into the stage beneath Mr. President, and kills him.

Unlike Rollerball the end of film has a positive aesthetic. A quick flash forward shows Frankenstein and Annie married, and Frankenstein assuming the position of the new President. He appoints Thomasina Paine as the Minister of Domestic of Security and announces that the Transcontinental Road Race will be abolished. All the while cheerful tones twinkle in the background.

The race announcer, Bruce, who throughout the film has voiced a particular fondness for violence, eagerly pushes back, “But Mr. President isn’t it true that as a racer your popularity entirely depended on violence?” Without an answer to his question Bruce approaches Frankenstein and Annie in their car insisting that he cannot call off the race. He stands in front of their vehicle pleading that the race is a symbol of everything the American people hold dear: “Our American way of life! Sure it’s violent! But that’s the way we love it! Violence, violence, violence! And that’s why we love you!” As he rambles on, Frankenstein revs the engine, and runs over Bruce, leaving him dead.

Unlike the victory lap that Jonathan takes at the end of Rollerball, the tone of the ending of Death Race 2000 sort of feels triumphant. However, a conclusion in which a new Mr. President and former athlete declares the end of a violent sporting competition by killing the commentator who just previously announced a race in which he was the star athlete, elicits a confused effect. Thus, like Rollerball it also nods to the clear limitations of resistance in a future capital structure governed by private companies.

Capitalist Realism

In some ways, the message here precipitates what the late Mark Fisher termed “capitalist realism” in 2009. In his book Capitalist Realism: Is There no Alternative Fisher diagnoses a widespread sense that people view capitalism as the only political and economic system imaginable. As a result, we have trouble envisioning any other future alternatives.

The films analyzed here bring up interesting questions as to whether they foresaw this idea or were critiquing its emergence. 1975 had not yet seen the fall of the Soviet Union and the subsequent rise of capitalism’s unquestioned dominance. Yet, it was viewing the beginnings of the rise of corporate influence in state and international politics and how people attempting to resist market dominance could get subsumed into its logics and narratives. Just as scholars of the Frankfurt school analyzed how the culture industry would draw resistance movements into capitalism’s ideological sphere, the same could be said of the sporting industry.

Sports—which at once were becoming privatized and commodified and yielding tremendous profit to corporate sponsors—were also seeing a rise in athlete activism, both in the ways they took public stands against hegemonic narratives and fought for their own admission into the professional ranks from a top-down structure that had previously deemed them amateurs—and therefore unable to be compensated. Athletes, then, embodied the simultaneous ability to publicly push against corporate structures while being embedded within them.

Forty-five years later, a global pandemic has laid bare many of the brutal realities of capitalism and the ways in which oil companies and sports enterprises prioritize profit accumulation rather than the lives of workers. Further, 2020 marks new, and inverted, crises in oil and sport. Unlike the hikes that doubled the price of oil in the 1970s, the price of oil dropped to negative $40.32 in 2020. And unlike the gradual professionalization of athletes corresponding with increasing profits, most sports have been cancelled, and reopening attempts in baseball and basketball have led to fractious disputes within the player ranks and between players and owners.

And still the notion of capitalist realism, backed by government support directed toward a corporate class and private industry, could be poised to retain its hegemony. With almost 40 percent of oil companies stopping production within the first few months of the crisis, those who do the hard labor of working on oil rigs may be deemed redundant.

Meanwhile, for sports owners and sponsors, prioritizing the profits of competition over the safety of participants may come by risking the health of athletes. Even Dr. Anthony Fauci, the head of the US Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, prioritized a plea for baseball to begin before other sectors of the economy were safe to open as early as April. Cloaked under his own enjoyment, he said, “I don’t think there’s any place that I relax more than sitting in Nats Park and watching my now world champion Nats play a game.” Athlete resistance has already been met with comments like Mr. Bartholomew’s urging people to stay out of management decisions. The lessons of the 1970s can tell us that, like athletes who will lose contracts or safe working conditions, the executive class is positioned to make out well.

However, alternatives to dystopian futures do seem to be arising in this wake. With a slight improvement in environmental conditions due to the slowdown of fossil fuel production and usage, the obvious mistreatment and underpayment of essential workers forced to work in dangerous times, and the lack of a safety net that a capitalist society fails to promise, the potential for tides to turn seems palpable.

Coming on the heels of a strong Bernie Sanders run, the Democratic Socialists of America have seen an increase of ten thousand members in response to current conditions. Movements around Medicare for All, basic incomes, and debt dismissal seem to be gaining more traction. Some are saying that the re-opening of the economy is the perfect time to inaugurate a global Green New Deal. And protests that have emerged nationwide in the wake of police brutality have seen unprecedented numbers.

Athletes, current and former, have been the most prominent voices in these tumultuous times. Some have taken the time to remind officials and sponsors that athletes’ health should be prioritized over sporting capital, using the opportunity to politicize the meager salaries and lack of protection that the vast majority of athletes regularly face and draw attention to the ways that capitalism and racism intersect in pernicious forms through a deadly pandemic and fatal police brutality.

Of course, political movements don’t happen by themselves, and without concerted efforts, we would be foolish to look past some of the absurdities that Rollerball and Death Race 2000 accurately predicted about the economic and social conditions of their future and our present. The question of capitalist realism and its viability then may present a productive question for us to grapple with in the midst of a crisis: What might, or rather, what could, sport, the energy economy, corporate structure, and working conditions, look like in 2065?

Hannah Borenstein is a PhD Candidate in Cultural Anthropology at Duke University and a freelance writer. She writes and does research about the relations between sports, capitalism, labor, race, gender, and politics. She tweets intermittently @hborenstein23.

This post may contain affiliate links.