This piece was originally published in Full Stop Reviews Supplement #6. You can purchase the issue here or subscribe at our Patreon page.

When on June 26, 1956 Congress approved the largest infrastructural project in the US to date—The Federal Aid Highway Act—America was to become the most mobile country in the world. An investment of $25 billion to build 41,000 miles of interstate highways by 1972 was a state-defining initiative which brought with it a promise of an unprecedented mobility. It was also in June 1956 that the Library Services Act (LSA) was passed in Congress; the first federal aid program in US history introduced to support library infrastructures.

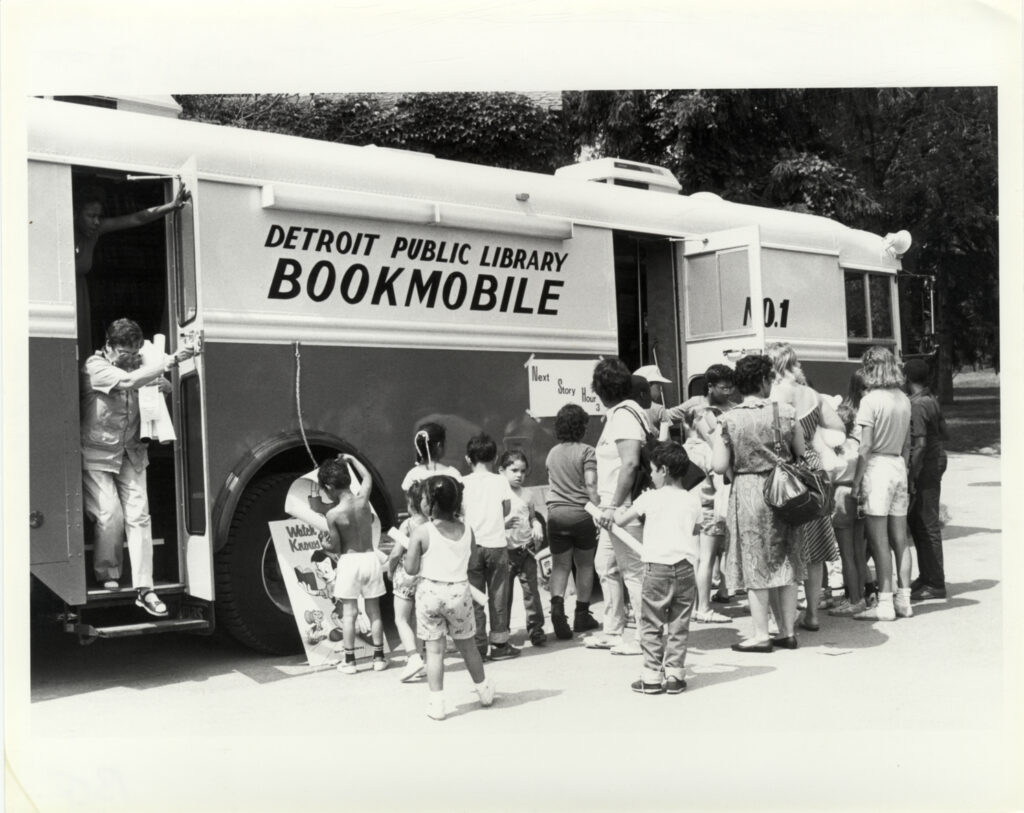

The LSA was to provide an annual appropriation of up to $7.5 million per year for five years for the introduction, extension and improvement of rural public library services. Under the State plan, funds could be used for salaries, books and other library materials, library equipment and operating expenses, but not for purchase of land or new library buildings. Targeted at communities with limited or no library facilities, the LSA, paradoxically, prohibited the creation of the very facilities, where they were needed most. In its shortcomings, however, the Act inadvertently contributed significantly to the expansion of library networks thanks to the increased use of mobile libraries. The constraints of the new funds meant that bookmobiles became the key means of book circulation and the most effective way of expanding the libraries’ reach. By using public highways for transport and public spaces, from town squares to parking lots as their hubs of library activity, the bookmobiles made possible widespread book circulation without extensive and expensive book circulation infrastructures. Their proliferation was widely supported and received enthusiastically, so much so that one new avid reader described the bookmobile as “the best thing . . . since they paved the roads.”

While, of course, not explicitly driven by the introduction of the Highway Act nor designed in response to the emergent network of roads, the Library Act transformed American library infrastructures in ways that were inevitably shaped by and intrinsically linked to the development of new and improved mobility infrastructures. It is this coincidence of car and culture that interests me here, and the ways in which circulation of books was shaped by this new expansion of American mobility in mid- and late twentieth century. I read real highways—rather than the information superhighway—as both a metaphor for the fantasies of automobile connection that they induce and as a physical space that shaped and reshaped the American reading public.

This relationship between the library and the bus—the book and the twentieth-century forms of mobility—is, of course, not new. In the US, the history of this form of library service goes back to the early twentieth century. It has roots in progressive education movements at the turn of the century and related broader ideological commitment to developing new infrastructures as a project of community—and through that—nation building. Early book mobility took many forms: Books were circulated from canal boats in Washington, DC, by mountain pack mules in Kentucky and Tennessee, while small reading rooms for railroad workers were set up in railroad cars. But it was the 1960s and 1970s that saw a real boom in mobile book circulation, which was a direct consequence of the burgeoning car culture at the time.

In 1904, there was one bookmobile in the US; in 1937, there were sixty; and by 1965 there were over two thousand all over the country. By the mid-1960s, one in every six libraries in the US operated a mobile service. The book buses became so popular, that car manufacturers started producing bookmobiles ready for use, and Bro-Dart industries, a library supply company, made a line of fully furnished trailers complete with books which were fully processed, catalogued and ready to roll. “Here comes the bookmobile!” became a familiar, somewhat iconic slogan in twentieth-century newspapers and magazines, memoirs, novels, and children’s books alike. The prominence of the bookmobile in American imagination was such that when the American Book Publisher Council was invited by the Department of State to send a book display to the 1959 American National Exhibition in Moscow, it was a bookmobile that was chosen to represent the American reading culture.

The mobile library of the period played a crucial role in encouraging widespread reading, in supporting and improving access to education and in shaping local communities. It encouraged library use through its informality: As Eleanor Frances Brown wrote in her pioneering 1967 study of mobile libraries, “There [was] no austerity or speaking in hushed voices” in the familiar bookmobile. In its approach and reach, the bookmobile, then offered an important alternative to the established cultural institutions not limited to big cities and state capitals, and was shaped, in no small part, by grassroots efforts of local communities that it later came to serve. As such, it inadvertently introduced another way of thinking about ways in which printed matter and information can travel and opened up novel possibilities for mobilizing also among countercultural and underground publishing communities prominent at the time; a model which these communities readily adopted. I suggest that this moment of ‘peak infrastructure’ in American history, marked by the introduction of projects such as the Highway Act and the Libraries Act, should also be seen as a tipping point in the shaping of the American alternative print and publishing cultures and that the bus should be considered a distribution infrastructure that is central to thinking about both politics and the poetics of what I will discuss here under the umbrella term of small press publication. In other words, it is no coincidence that this key moment in the history of American mobility was also the small presses’ golden age.

In what follows, I present a brief history of the small press bookmobile—a story of America’s cultural and physical geography and means of navigating both—which in its somewhat nostalgic take on countercultural publishing, offers a powerful story of that which is included and that which is omitted from the mainstream reading cultures; i.e., a story of the politics of distribution of knowledge. At stake, then, is a largely ignored history of an increasingly obsolete model of book distribution as a lens into the twentieth-century textual cultures.

The bookmobile was among the most influential infrastructural projects in the twentieth-century US to have shaped reading habits. Its appropriation by the small press community, although on a relatively small scale, played a crucial role in forming independent publishing communities. The small press in this context should not be considered synonymous with any ‘small’ publisher. It is instead a press characteristically unaffiliated with academic institutions or major media conglomerates, not motivated by profit and committed to often difficult, avant-garde forms of art and writing that grew out of the moment of political activism in the 1960s and 1970s. That is, on their small budgets and through their very small operations the presses I talk about when I talk about the small press here created a whole sphere of publishing that existed parallel to the mainstream and included material notably absent from it.

Stories of distribution struggles are among the most frequently recurring narratives emerging from the 1970s small press community. Distribution was both “the number one problem for the independent small press” of the period and “the last thing that anyone want[ed] to talk about,” and proved a central factor in the shaping of the emergent small press reading public. What is important to understand about the publishing ecology of the small press is that these publishers emerged en masse in the 1960s with no infrastructures to support their publications’ circulation. Mimeo, new, affordable forms of offset printing, and later Xerox might have made possible homegrown and relatively cheap publication on an unprecedented scale but getting these new books to the readers was a major challenge. While the small press as a viable, if niche, publishing outlet was growing at a rapid pace at the time, its books remained primarily accessible to other small press writers and publishers. Their marginal status meant that they were missing from mainstream bookshops, they were excluded from libraries, and they often didn’t have the capacity to place their publications in those most visible networks of distribution. No mainstream distributor would carry small press publications well into the 1970s. A growing network of independent bookshops, including feminist and black bookshops, played an important role in small press circulation, but it wasn’t substantial enough to enable large scale distribution. Their focus on the politically engaged, activist communities also meant that these new spaces for reading and selling books reached mainly those already in the know and didn’t ensure a more expansive access to small press publications. Enter the book bus. Its introduction at the time was seen as an answer to these very challenges.

One prominent example of a small press distribution infrastructure which developed based on the mobile library model was the Visual Studies Workshop’s (VSW) Book Bus. A non-profit dedicated to art education in Rochester, New York, the VSW has been in operation since 1969. Today, it runs an MFA programme, a bookstore, a gallery and a library. Predominantly associated with photography and the photo book, the workshop has a long tradition of print and publishing, including an independent press of its own supporting all forms of independent publication, not exclusively visual.

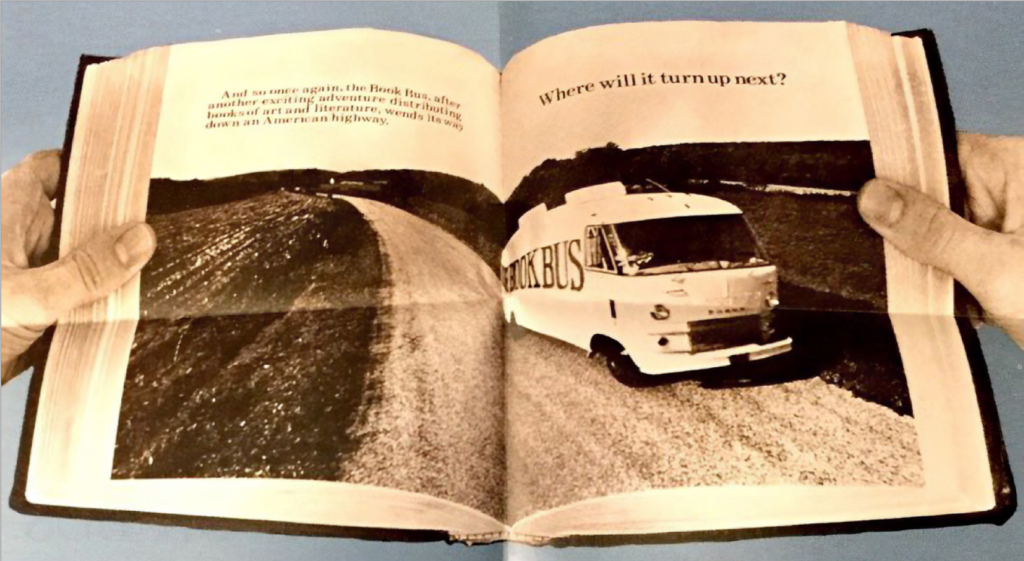

In 1976, at the time of its most intense activity, the VSW introduced to its portfolio of activities a mobile home redesigned to operate as a bookstore and to provide a travelling outlet for selling small press books it published and/or distributed. Its introduction was an attempt at making small press publishing visible and accessible on a much larger scale, beyond the city of Rochester. The VSW didn’t purchase a custom-made bookmobile—the popularity of these units from mid-1960s onwards meant that they became an expensive and increasingly coveted commodity. Instead, the Workshop took over a book bus run by Jonathan Williams of Jargon Society and Black Mountain College between 1972 and 1974, with partial funding from NEA and The New York State Council.

Williams’s book bus was used first and foremost to distribute books published by his own press, and a select few with which he collaborated, but its inclusion in The VSW programming meant that its scope expanded to a three-part distribution service comprising the bus, a mail order distribution, and a local bookshop in Rochester; a system developed for independent press books, including poetry, photography and experimental publications of all sorts. Its stock was eclectic and fiercely independent: “There are no best sellers on the Visual Studies Workshop’s Book Bus,” wrote Sally Euclaire in her 1978 VSW profile for a local newspaper, Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, “but there may well be some best sellers of the future. The bus carried Patti Smith’s poems before she became a rock star. It handled the Whole Earth Catalog . . . before [it was] picked up by major publishers.”

The project grew quickly. In 1978, the bus covered fifteen states and the District of Columbia and exposed over 35,000 readers to independent press books at conferences, universities, museums, libraries, arts organizations, and poetry readings, but also mall parking lots, markets, and petrol stations; it went wherever it could find an audience. Its success varied greatly: “At the colleges,” wrote Joe Flaherty, the VSW Book Bus coordinator, “it often depends on the teachers and often the schools with good academic reputations are the worst. There are old and distinguished professors in English departments who frown upon anything contemporary.” But regardless of the obstacles—and ongoing technical issues posed by the cheap, old vehicle not kitted out to carry a heavy load of books, the operation was significant and impactful. Between July 1977 and July 1978, for example, the Project sold over eight thousand books, returning $20,000 (the equivalent of $85,000 today) to the publishers that participated in this program.

Similar to the VSW Bus, the COSMEP Van run as a small press distribution initiative. COSMEP—the Committee of Small Magazine Editors and Publisher—was a small co-operative when it was first set up in 1968 in California but grew into a major national small press organization with over one thousand members across every US state just ten years later. It was established to support small magazines, but quickly developed to work with small presses in general, in all aspects of their publishing activity. COSMEP saw itself as an important advocate for the small press community and a platform for exercising its socio-political potential, i.e., it saw the small press as a means of ensuring that “literature, social commentary and visual arts do not become the domain of a select or powerful few.” For these very reasons, distribution was one of the key issues on COSMEP’s agenda throughout its history.

The COSMEP van project also launched in 1976 and like the VSW Bus, was regional in focus. COSMEP’s van, however, covered thirteen states in the Southeast US and had its headquarters in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Although the rural Southern readers were judged to be one of the most difficult markets to sell, the South was also home to the richest mobile library movement. North Carolina was for a long time the state with most prominent mobile library service in the country and the highest number of bookmobiles in use. As such, North Carolina and its surrounding states proved a natural home for a small press book bus project. It offered a context in which this form of book circulation, and with it a possibility of reading as an activity for many, was deeply embedded in local imagination.

While VSW ran a curated collection of books, chosen by the bus project coordinator, the COSMEP bus would carry publications of any of the organization’s members. In 1978, COSMEP van distribution included six hundred presses and over one thousand publications in an attempt to reach communities which otherwise didn’t have access to small press books and to expand small press readership in support of its democratic vision.

The use of a bus as a book distribution infrastructure was very much of the moment when VSW and COSMEP launched their operations, but they appropriated this well-established model of library book circulation as a different kind of book infrastructure. For these small press collectives, it was a new means of selling books, co-operatively, and to communities which often didn’t have access to any bookshops at all, recognizing the potential of the small press to reach a much wider audience:

We go anywhere . . . We’re unique enough to pique people’s curiosity. Our feeling is that if they get a look they’ll be interested.

A new system for creation, distribution, and management of small press reading public—of collective consciousness of the small press as a reading possibility—was central to the introduction of the book bus as a small press distribution infrastructure. The familiarity of the bus as a space of reading—one associated with the long tradition of the library—was, in fact, an ingenious publicity move. By using the established, well-loved format of the bookmobile, the small press book van brought with it a promise of the familiar reading experience, both in terms of the space that the bus created and the reading material that it made available—of books for the community. But under the guise of a familiar bookish infrastructure, it presented a very different reading experience; a carefully curated collection of poetry pamphlets, experimental prose, and photo books, i.e., the kinds of publications that would have never arrived on the traditional library bookmobile. It was this illusion of familiarity that allowed the travelling small press bookshop to propose the unfamiliar small press publication as a reading possibility in the first place.

The small press book buses were as much an awareness-raising exercise as a means of selling books. But profit did play a part in these distribution activities, and the ideology of activist entrepreneurship and grassroots business-making, so prominent in the 1970s, was not absent from these projects. They were set up in no small part to improve the financial situation of the participating small presses. But in running affordable book sales programs rather than library schemes, the buses also stressed the importance of owning books, of building a personal library, of cultivating a taste for collecting books among those who perhaps didn’t have the capacity to do so otherwise. Their project was both a matter of economic self-sufficiency as an activist gesture, and a means of developing a small press reading public. And although successful in reaching widespread rural communities and significantly expanding the audience for the small press, the buses didn’t survive. The COSMEP van shut down in 1979, the VSW book bus project lasted until 1981.

The reasons for this short-lived operation of both buses were many. Decline in public funding and the restructuring of the NEA Literature program, dramatic increases in postal rates (of significance to the mail order part of these projects), growing production costs, as well as rapid and dramatic commercialization of the book sector all meant that the small press found itself in crisis in the late 1970s. The set of socio-economic conditions that, first, made possible a co-operative, publicly funded, small press organization to run a book bus operation also made that very operation an impossibility just a few years later. In the 1980s, the small press found itself in decline at least in part due to a set of transformations that affected the new infrastructures of mobility. The increase in oil prices following the 1973 oil crisis and related economic transformations proved disastrous for small independent organizations, resulting in a decrease in the possibility of affordable, self-organized travel among grassroots publishing communities which relied on small scale mobility.

In fact, The VSW Book Bus project didn’t fold altogether. Instead, it transformed into Writers and Books—a bookshop and a cultural center in Rochester which is still in operation. The need for distribution was still present, but the models used to date became unsustainable. This crisis of mobility, combined with decline in public funding meant that the small press as a movement—and its institutions—were unable to sustain themselves, at least not on the scale that existed in the previous decade. And as Lauren Berlant tells us, “institutional failure [leads] to infrastructural collapse.”

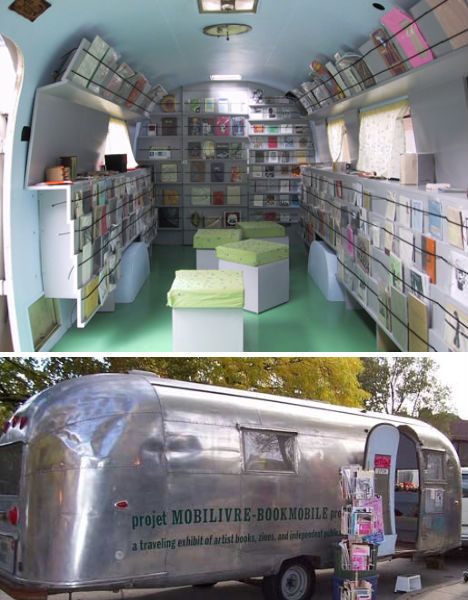

The small press was fairly invisible in the 1990s, but it subsequently re-emerged in the early 2000s, both thanks to the possibilities offered by the internet as an alternative distribution infrastructure and the crisis of publishing after the most recent financial crisis, when the need for an alternative was yet again felt more strongly. A renewed interest in the book bus model of book distribution has also been noticeable since. Between 2001 and 2005, The Mobilivre Bookmobile project, set up by Bookmobile Collective traveled across the US and Canada in a vintage airstream trailer distributing books, zines and independent publication. Parnassus Book, a bookshop in Nashville, have since 2016 been running a bookmobile, often stopping at food track rallies, farmer’s markets and outside restaurants (and there is, as Rachel Bowlby points out, a long and established, if perhaps peculiar history of the relations between book-selling and food-selling.) In Los Angeles, Twenty Stories do the same using a renovated 1987 van, as do Fifth Dimension Books in Austin, Texas. And the list could continue.

But the most recent attempts at returning to the book bus model as a tool for independent publishers and booksellers are informed by a different infrastructural logic than the 1970s projects. The 1970s small press community, in using the existing and expanding infrastructures—the roads, the buses, but also the libraries and proliferating independent bookshops—worked to create a new small press reading infrastructure as both a physical space for reading and a small press imaginary that grew out of its countercultural credentials. COSMEP’s library activism (of which I write in more detail elsewhere), for example, was a way of engaging the institutions and infrastructures in place to create new support structures for the small press, to establish a small press commons. In that sense, the bus was both a tool of building an institution and an infrastructure in its own right—in its act of navigating spaces of reading, it rendered visible the accessibility of existing forms of organization.

In contrast, the return of the bus in the last decade can be seen as a symbolic manifestation of infrastructural and institutional failures, a response to the destabilization of public and private institutions, and a result of destabilization of power which means that institutions also become less stable and more mobile. In this sense, the new mobility of the publishing community becomes a metaphor for what Paul Virno describes as the contemporary condition of global homelessness, one he sees as a characteristic of the contemporary commons, where logistics becomes so much more than a question of moving things; it becomes a crucial form of organization of life.

The book buses today have limited capacity to build on existing infrastructures and institutions. Instead, they become a means of filling in the gaps left by the declining infrastructural capacities, the disappearance and lack of investment in other institutions; the very institutions that made the emergence of this form of book-mobility possible. In its flexibility and entrepreneurial enthusiasm, the bus today then is an uncertain, temporary infrastructure that shapes contemporary precarious economies and makeshift ecologies of small press publishing in particular, but also all forms of independent cultural production in general.

Kaja Marczewska is a researcher, writer, and museum professional based at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, UK. Her work focuses broadly on networks, institutions, and infrastructures of knowledge production, especially as they shape and are shaped by book and print cultures and grassroots, independent, and experimental approaches to art and writing. She is the author of This is not a copy (Bloomsbury, 2018) and a co-editor (with Leigh Wilson and Georgina Colby) of The Contemporary Small Press (Palgave, 2020).

This post may contain affiliate links.