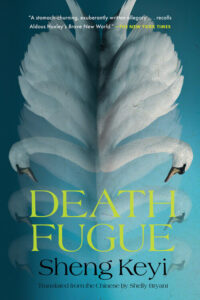

[Restless Books; 2021]

Translated from the Chinese by Shelly Bryant.

Ever since Francis Bacon described the mythical island of Bensalem in his novel, New Atlantis, four hundred years ago, novelists have been imagining the existence of faraway, utopian lands as proffering hope or a grim prediction of how we might one day live. And Chinese author Sheng Keyi’s novel Death Fugue is a marvellously odd addition to this genre, one typically dominated by Western writers. Published by Restless Books and translated by Shelly Bryant, Death Fugue is an allegorical tale, but whether it is a utopia or dystopia is beautifully unclear.

It can be tempting for authors of utopian and dystopian novels to fall into the trap of allowing bold ideas to overtake artistic endeavor, resulting in bland polemic, where shapeless characters represent ideas, devoid of the rich complexity of human experience. For example, Edward Bellamy’s, Looking Backward (1888), foresaw a future where machine-led technology enabled a worker’s paradise, yet it reads more like a political pamphlet than a novel. It was a technocratic solution abhorred by fellow socialist, William Morris, who responded with his own utopian novel, News From Nowhere (1890), an ode to the pleasures of a bucolic, agrarian existence; a very different utopia to Bellamy’s albeit one also filled with characters who exist only to establish and map its authors political beliefs. Unlike Bellamy and Morris, Keyi eskews ideology, choosing not to provide a blueprint for her own political fantasy; she instead looks backwards to China’s lush, pastoral landscapes and poetic history, as well as forward, to the modern, technological age, in order to imagine an alternatively structured society that is truly lived and not simply explained. Rather than a political tract shaped like a novel, Death Fugue — through character, language and ambiguity — explores societal themes such as advancing technology, state control, individual freedom, sexual liberation and the pleasures of the natural world, allowing the reader to decide for themselves if it is hope or fear they should be feeling about the future. There are no answers to the riddles of moral and political questions and ideas evoked in Death Fugue; instead, moral judgement is left hanging for readers to hesitantly pick at, because, in reality, society does not operate like a clear political statement, it is confused and filled with flawed and feeling people, just like the characters in Death Fugue.

Sheng Keyi was a teenager during the 1989 massacre in Tiananmen square — a government crackdown on student protests which resulted in armed troops firing at the demonstrators and is now thought to have killed tens of thousands of people. Keyi, who was raised in the countryside, far away from the city, received the censored version of events, believing the government to be blameless, and had no idea of the numbers who had died. A large section of Death Fugue is a retelling of the Tiananmen massacre, a way of setting the record straight perhaps; although it is given a surreal twist by originating not with debate over party reform, but with a huge tower of excrement forming in the fictional city of Beiping’s Round Square. Speculation as to how the excrement came to be in Round Square intensifies when the government fails to provide an explanation. Just like in Tiananmen, months of protests, including hunger strikes, continue until martial law is declared and the tanks roll in with devastating consequence. Mengliu, the book’s protagonist, is a poet working in the Wisdom Bureau whose great love, Qizi, goes missing in what becomes known as The Tower Incident (in China, Tiananmen is referred to as ‘June Fourth Incident’). Twenty years later, after forgoing his life as a poet and becoming a surgeon, Mengliu decides Qizi must still be alive and sets sail to find her; whilst travelling, he is caught in a storm and washes up on the shores of the idyllic Swan Valley.

Whilst shipwrecks on fantasy islands are a common trope in utopian fiction, including Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) and Aldous Huxley’s Island (1962), Keyi’s description of The Tower Incident — which provides a reference to real world events — feels wholly original, placing her characters within a significant historical context and specified timeframe rather than a disconnected, imaginary world of the future. Once again, Death Fugue is not merely an intellectual exercise in critiquing or promoting a potential reality, like so many utopian/dystopian novels, but an attempt to engage with the complications of history as a precursor to any future society. Just as Tiananmen still lingers in the memory of recent Chinese history, The Tower Incident continues to haunt Mengliu as he is welcomed into Swan Valley’s peaceful community, where art and beauty are cherished and its leaders are poets and philosophers. Unlike Mengliu’s home city of Beiping, which is environmentally ravaged, Swan Valley is a lush, pastoral paradise, like the countryside of Keyi’s upbringing or Morris’ News From Nowhere.

Mengliu is invited to live with Juli, who explains the customs and beliefs of the seemingly tranquil, spiritually inclined Swan Valley. Like all women who cross Mengliu’s path, Juli’s desirability is immediately assessed and her sexual attributes described in surprising ways: “Her chest boasted a pair of loaded coconuts, a potent pair of aphrodisiac tear-gas canisters. Day or night, if she willed it, she could pull the pin and instantly fill the world with smoke.” Given the use of tear gas in Tiananmen this is a subversive use of metaphor, bringing to mind the relationship between sex and violence. Whereas, in Swan Valley, sexual intercourse is prohibited (a disappointment to Mengliu), which, continuing with Keyi’s use of metaphor, creates a sharper juxtaposition between the place Mengliu left and the place he resides now. Instead, couples are matched according to their genetic compatibility and all pregnancies occur from artificial insemination — “a clean, painless little procedure” according to Juli. The sudden announcement of an advanced scientific underpinning life in Swan Valley by way of reproductive technology, switches the narrative from Huxley’s Island to his Brave New World (1932) and introduces the theme of childbirth, a common subject in utopias — such as in Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time (1976) where female pregnancy is no longer a necessity — and dystopias alike — notably the enforced motherhood of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985).

Gradually, over the course of Mengliu’s stay, Swan Valley is exposed as having an underbelly far more sinister than its tranquil surface suggests. Like a bumbling P.G.Wodehouse character, Mengliu falls in love with many women after only the briefest of interactions whilst learning the disturbing truth about Swan Valley and its statist methods, stripping the rights and freedom of its citizens, which like Keyi’s experience of Tiananmen, gets presented as something else. He is not portrayed as a predator or violent misogynist, but a naively, lustful man who can only — or perhaps only allows himself to — understand women in one way: as objects to be desired, there to be conquered by his charm. Keyi presents Mengliu as being deluded by his own sense of romanticism, reducing him to the role of fallible companion rather than moral hero. He is as imperfect and beholden to his own ideas as the places he travels to and from. Just like the calmness and beauty of Swan Valley — “like a curtain of falling water” — Keyi’s prose flows lightly, as if on tiptoes, showing no anger or clumsy weight of moral judgement.

Death Fugue is an allegorical tale as chilling in parts as anything by Atwood or Yevgeny Zamyatin, yet told with airy, fitful surrealism. It is a novel that admirably refuses to slip into the genre’s habit of pedagogy or proselytism, instead people are addressed before politics, living their lives under systems of governance in which they must make a choice to either accept or fight against. Banned from publication in mainland China, despite Keyi’s past success and popularity, Death Fugue is both reposeful and purposeful, an unerringly calm vision of beauty and terror.

Simon Lowe is a British writer and journalist. His stories have appeared in Breakwater Review, AMP, Storgy, Firewords, Ponder review, and elsewhere. He has written articles about books and society for the Guardian and BBC worldwide. His new novel, The World is at War, Again, was published in 2021 (Elsewhen Press).

This post may contain affiliate links.