This essay was first made available last month, exclusively for our Patreon supporters. If you want to support Full Stop’s original literary criticism, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter.

Ali Smith’s seasonal quartet is often read as protest literature responding to Britain’s divorce from the EU, but it also tells a fascinating tale about family and (budding) friendship. At heart, Autumn, Winter, Spring and Summer ask us: what holds people together who are living through this political moment of breakage?

Described as an “insistently political writer” by The New Yorker, Ali Smith has been addressing social problems through fiction since the start of her writing career—from homelessness to consumerism to cyber bullying. In her latest series of novels, the Scottish author has switched to delivering near live commentary, by book publishing standards at least, engaging directly with narratives surrounding social and economic inequality, fake news, racism and immigration in post-referendum Britain.

The speed at which she responds to these developments may be fairly unique, yet her interest in the aspect of novelty in literature is not. The recent historical novel has been on the rise for a while, as Alexander Manshel noted in an article on Post45. This type of writing positions itself in the space between literary fiction and contemporary journalism, with notable examples being Jesmyn Ward’s Salvage the Bones, set during Hurricane Katrina, or Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americana, in which Obama’s presidency features. These novels, writes Manshel, fictionalize the crises of recent history before they become fully historical. The genre affords its readers the pleasure of witnessing as the events of their lives become literature, history.

In 2014, Ali Smith realized that the novel could be pushed to be even more novel, when publisher Hamish Hamilton managed a six-week turnaround on her technically unprecedented novel How to Be Both, consisting of two sections printed and distributed in random order. Smith then got the idea to write a sequence of books called Seasonal, each dealing with a season, written in a relatively short time and as contemporaneous as could possibly be. “The concept was always to do what the Victorian novelists did at a time when the novel was meant to be new,” Smith told the Guardian last year. “Dickens published as he was writing Oliver Twist. He was still making his mind up about the story halfway through. That’s why it’s called the novel – what it can do, what it’s for, what it does.”

She started writing her seasonal quartet two years later, in the year Britain voted to leave the EU, making Autumn one of the first Brexlit books. In a nod to Dickens, the story starts in the “worst of times,” as 32-year-old Elisabeth Demand, unsettled by the outcome of the Brexit vote, sits by the bedside of her 101-year-old friend Daniel Gluck in a care home. In a narrative that flicks through the decades, resembling the experience of watching Insta-stories, we learn how Elisabeth found a father figure in Daniel as a child, and how Daniel lost his sister Hannah in the Second World War. While Daniel is asleep, oblivious to the state of the country, Elisabeth’s mother Wendy experiences an awakening, starting to fight surveillance company SA4A and finding same sex love.

By the time follow up Winter came out in 2017, the times had gotten arguably bleaker. Trump was in office, Grenfell had burned, Jo Cox had been murdered. On “a bright sunny post-millennial global-warming Christmas Eve morning,” nature blogger Art finds himself newly single, after yet another row with his partner Charlotte, who thinks he should stop marveling about warblers on his blog and write about the havoc climate change wreaks on the natural world. When Art spots homeless Croatian immigrant Lux at a London bus stop, he offers her £1000 to pose as Charlotte during the holidays. Art and Lux-pretending-to-be-Charlotte travel to Cornwall, where they spend Christmas with Art’s leave-voting mother Sophia and his progressive activist aunt Iris, and – in another nod to Dickens – the ghost of Christmas past.

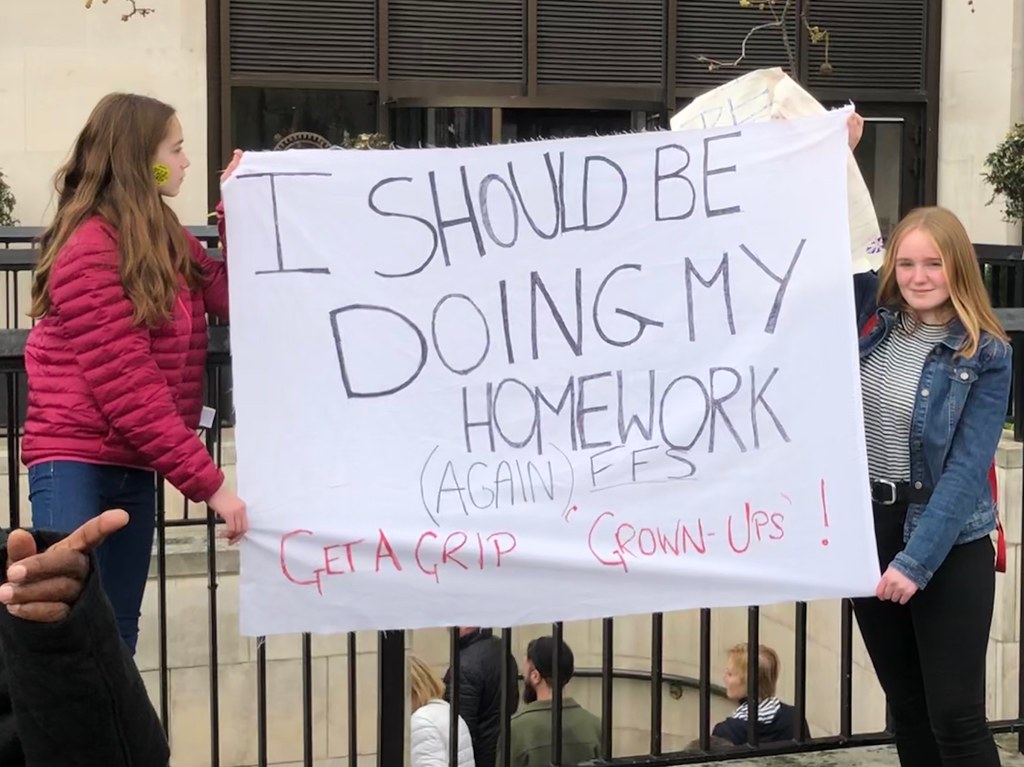

By the time Smith started writing Spring in 2019, teenagers had taken up school strikes for the climate. In keeping with the season, hope shines through the novel’s pages. Florence, a refugee girl who matches Greta Thunberg in determination and eloquence, enters Immigrant Removal Centers run by SA4A to demand better circumstances for detainees. She stops washed up film director Richard Lease from jumping on the tracks at a train station. In the road trip in a coffee truck with a crew of strangers that follows, she opens his eyes to his privileges and instills a sense of compassion in him.

And now there is Summer. Released in August 2020, Smith re-wrote and re-filed the manuscript to incorporate the Black Lives Matter protests, leaving editors with three days to proofread. Summer starts in February 2020, when Australia is burning and COVID-19 has started showing its ugly head around the world. Newly single mother Grace voices one of the dilemma’s central to the novel when she tries to remember the opening sentence of – Dickens again – David Copperfield: “Whether I shall turn out to be the heroine of my own life.” It’s a question that is even more urgent for her two children, the young protagonists of this novel: sixteen year old Sacha Greenlaw, a Greta Thunberg adherent who has befriended a local homeless man, and her 14-year-old brother Robert, who is a fan of Albert Einstein and hates most other things since radicalizing on a 4Chan-like place. How much of a say will they have in their own future when the world is already quite literally burning?

In a move that brings together characters from all previous novels except Spring, Sacha, Robert and Grace cross paths with Art and Charlotte from Winter and embark on a road trip that will lead them to Elisabeth and Daniel from Autumn. It is not the first time that strangers are sharing train seats, cars or bedrooms within hours of meeting, which at times comes across as theatrical and implausible. Such chance meetings and impromptu acts are characteristic of the magical realism Smith dabbles in, but the way the sweeping societal changes the characters are living through affect their personal relationships is chillingly realistic. As much as these novels are about politics, they can be read as a commentary on what family means today, a theme made more explicit in Summer, its blurb asking “So: where does family begin?”

In Smith’s writing, family rarely begins with an intact traditional mom, dad, two kids kind of family. Instead, the majority of her oeuvre features broken families. In the seasonal quartet, every character under 35 grows up in a single parent household, reflecting that the UK has one of the highest numbers of children growing up in single-parent families. To explore tensions in family relationships, Smith’s tool of choice is the introduction of a stranger, who evokes strong feelings in the other characters (a road previously taken in her books How to be both and The Accidental). These strangers usually take the shape of whip smart, outspoken young women who upend the traditional coming-of-age story, like Lux in Winter or Florence in Spring, while in Autumn, it is Daniel who most embodies the trope of the uncanny other. All three of them are (perceived as) foreigners, perhaps Florence most of all, as an unaccompanied minor refugee of color. Their mere existence brings political divides to the fore; as the other characters are confronted with their privileges and prejudices through meeting these strangers, it reveals their thoughts about who belongs and who doesn’t – one of the questions at heart of the Brexit referendum.

The Leave-Remain divide in Britain, much like the anti and pro Trump divide in the US, is often seen as one group pitted against another, with geography, age and income as determining factors in how people vote. But, as Professor of Politics at the University of London Eric Kaufmann has argued, invisible differences in the level of attitudes and personality – in particular the difference between open and closed personalities – have a bigger influence on voting choices. In fact, a British Election Study from 2015 found that one of the strongest indications that a person would vote Leave was support for the death penalty, even though this was not a campaign topic. These differences in values don’t pit one group against another, but rather slice through groups, communities and even families. Smith has carefully woven this schism into the quartet. Sisters are estranged from sisters and mothers from daughters as they stand on opposite sides of the Leave-Remain divide. With real life polarization growing, in Summer, divisions between the characters have also deepened. Summer’s Greenlaw family brings the American Conway family to mind: siblings Robert and Sacha hold opposing views about Brexit, as do their recently divorced parents.

In the seasonal quartet, confrontations with strangers like Daniel, Lux and Florence, show that rather than being insular and inviolable units, families consist of multiple people who hold different values. Here, the personal serves as a parable to the political: despite its island identity, which it has been seeking to strengthen by leaving the EU, Great-Britain is made up of two large and over 5000 small islands, not all of them on the same page about Brexit.

In Smith’s writing, the presence of the stranger destroys the social order, but in doing so, space is opened up for the creation of new communities and kinship systems. This happens for example in Autumn, when Daniel Gluck strikes up a friendship with his young neighbor Elisabeth at a time when her mother Wendy has difficulty looking after her. At first, Wendy disapproves:

Don’t be rude, her mother said. And what you are is thirteen years old. You’ve got to be a bit careful of old men who want to hang around thirteen year old girls. He’s my friend, Elisabeth said. He’s eighty five, her mother said. How is an eighty five year old man your friend? Why can’t you have normal friends like normal thirteen year olds?

The nature of this friendship may also make readers uneasy. When Elisabeth is jealous after Daniel tells her that there is someone he loves more than her, we may think we know where this is going. But then the story doesn’t actually go there. Daniel doesn’t take advantage of Elisabeth. So why does this friendship initially evoke suspicion? Perhaps it is because friend groups tend to be quite homogenous, with people mostly befriending people of the same gender, age and level of education. The more similar people are, the more likely they will meet and become friends. In Britain, different generations struggle to cross paths: about fifty percent of the population in cities such as London, Birmingham and Manchester is under 30, while old people dominate rural and coastal areas. Intergenerational friendships, like the one between Daniel and Elisabeth, have become rare.

In the seasonal quartet, they flourish, and not just in Autumn. “Art is seeing things,” Winter states, and often it is art that brings characters of different generations together, sparking their curiosity and inspiring them to be more empathetic. Elisabeth and Daniel share a passion for the in-your-face collages of pop artist Pauline Boty, and Lux and Sophia bond over Shakespeare’s lesser known play Cymbeline, while all characters take pleasure in playing with language. As they exchange thoughts about art and through puns, they veer out into issues that show a stark age divide in opinion polls, from #MeToo, Black Lives Matter and Brexit along to the climate crisis. Reading their conversations, one can’t help but wonder: would these differences be less significant in the real world if there was more interaction between young and old?

By the time Summer was published, that question has become even more relevant. As the world is fighting a highly contagious respiratory virus that is particularly dangerous for older people, care homes have gone into lockdown and young and old are urged not to mingle. As we keep our distance, barriers are pulled up between generations. Even more, the rule of six and other measures to stop the virus from spreading, make the kind of chance meetings with strangers that the seasonal quartet is built on even less likely to happen.

“Time spent exchanging life and times with complete or comparative strangers can sometimes work out rather well. In some cases, it can be even life-changing,” Art declares in Summer, as he and ex-girlfriend Charlotte take Sacha, Robert and their mom Grace on a trip to meet now 104-year-old Daniel Gluck. Before she passed away, Art’s mother Sophia had asked him to find Daniel and give him a round stone object, which is the missing piece of the sculpture mother and child by artist Barbara Hepworth, Daniel’s most cherished possession. Readers of the previous novels will have picked up on the fact that Daniel and Art aren’t as strange to one another as they think they are. Daniel was Sophia’s lover over three decades ago, and Art, who returns the stone, is his child.

Hints about this kinship, and that of other characters, are carefully sown throughout the novels, but surprisingly, not all of them come to full bloom in Summer. Daniel wakes up from one of his prolonged sleep periods to find that his memory has withered away. When he sees Elisabeth, he thinks of her not as his friend, but as “his neighbor’s daughter.” It might be memory loss, it might be that the friendship that shines so bright in Autumn is not reciprocal. When Art brings him the stone, equally, Daniel fails to understand its meaning. In fact, besides Art, more family members of Daniel Gluck show up – unbeknownst to all of them.

Wondering why Summer doesn’t end with a grand family reunion in which all is resolved, I submitted a question to the chat box of the Edinburgh Book Festival, where, 2020 style, Smith was presenting Summer through Zoom from her attic in Cambridge. Coming up as the final question, Smith had only a few seconds to answer. “To some extent, I didn’t really get a choice. These novels have been written on the hoof and they were an experiment on the hoof. And what came to me, I was like, ‘Yes! thank you for coming! Thank you for being part of this, so thanks to them [the characters],’” she said, echoing an idea she has previously put forward in interviews, which is that the book already exists and the author has to come out to meet it and excavate it and deliver it. There was a perfectly laid out path, but the story didn’t want to take it, Smith seems to say.

“But you know what, those other characters that you are wondering about, that’s the point in a way. Because you are now making up their lives. Good. I trust you to,” she added. And wonder about them I did. I wondered whether every story needs a climatic ending, or whether the end of a story always jumps into the mouth of its beginning, as author and mythologist Martin Shaw believes, and much like the seasons do. Does Elisabeth need to know that Art, whom she falls in love with, is the biological son of her own surrogate father? Would Daniel die a happier man if he’d know that in his brief, joyful encounter with Robert, he has met the offspring of his long-lost sister? Is friendship the answer to “where does family begin”?

To many characters of the seasonal quartet, the answer appears to be yes; whether they are or aren’t family, they feel like they are. And so Charlotte moves in with her ex-partner’s elderly aunt Iris to form an activist collective, while Elisabeth continues to provide care for her neighbour Daniel in old age. To lawmakers though, the answer appears to be no. In Autumn, when the care facility Daniel is staying in is unable to locate his next of kin, Elisabeth has to pose as his granddaughter to be able to see him, long before COVID-19 was even a thing. If Elisabeth is not Daniel’s family member or partner, the system considers her a stranger. In this case, it is not political differences that stand between two characters, but rather society’s rigidity that turns them into strangers, exposing how, though the idea of chosen family has become so mainstream that it is a category on Netflix, it receives little formal recognition.

In the UK, as in most countries, policy is still largely created with the nuclear family in mind.

Nonetheless, looking out for the wider community is encouraged, when convenient. In a bid to bring COVID-19 to a halt, politicians in the UK and elsewhere are urging citizens to show solidarity and extend care to those beyond their own flesh and blood. Many Brits clapped for NHS workers they’d never met, some even delivered groceries to the elderly and vulnerable in their neighborhoods. Urged on by slogans, they “stay inside to save lives,” are “vigilant” and “eat out to help out.” But, as one of the characters in Summer observes, sloganeering is “the opposite of giving control back to the people.” Rather, it is a sign of an incompetent government’s attempts to push its responsibilities onto citizens in a time of crisis. Looking out for those beyond our family and seeking community is part of the answer to how to deal with some of today’s most pressing challenges, but it won’t fix everything. This is the warning that the seasonal quartet relays. Or, as Daniel Gluck aptly remarks in Autumn: “When the state is not kind, the people are fodder.”

In an interlude of the quartet’s 2016 opening novel, Smith observed that “all across the country, politicians lied” in their bid to convince British voters to choose Leave. Four years on, those same politicians haven’t exactly become kinder, nor more truthful. In the same week that the United Kingdom passed a Brexit bill that will break international law, the president of the United States declared that “herd mentality” (sic) is a real cure to a pandemic that has killed over 1.8 million people and counting. Under these circumstances, do Sacha, Robert and the others young protagonists have any shot at becoming the heroines of their own lives?

Summer doesn’t offer up readymade answers and solutions. One of its qualities is in fact that it generously provides space for readers to invent their own stories. By breaking with conventions of style and form and by upending age-old narratives, Smith shows us that stories don’t have to go where we are led to believe they will. We can have an active part in reshaping them, and Smith takes the lead by bringing a large number of artists and artworks together in the seasonal quartet, (re)writing the stories of underrated or forgotten female artists like pop-artist Pauline Boty, sculptor Barbara Hepworth, photographer Tacita Dean and film-maker Lorenza Mazzetti, while also weaving in her own takes on British classics, including Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Cymbeline, Pericles and A Winter’s Tale and Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, A Christmas Carol, The Story of Richard Doubledick and David Copperfield. Reading the seasonal quartet provides a glimmer of hope that, though fire, plague and drought have already arrived, if we can imagine a different story, apocalypse does not have be the inevitable final page in the lives of Sacha and Robert and, by extension, young people enmeshed in those very same crises out in the world today.

Selma Franssen is a Dutch journalist living in Brussels. Her work has been published by the New Statesman, Bustle, the Island Review, and Dutch and Belgian national newspapers and magazines. In 2019, she wrote her master’s thesis in Literature at KU Leuven about family and friendship networks in Ali Smith’s seasonal quartet. That year she also published a non-fiction book exploring modern day friendship, titled Vriendschap in tijden van eenzaamheid (“Friendship in a time of loneliness”).

This post may contain affiliate links.