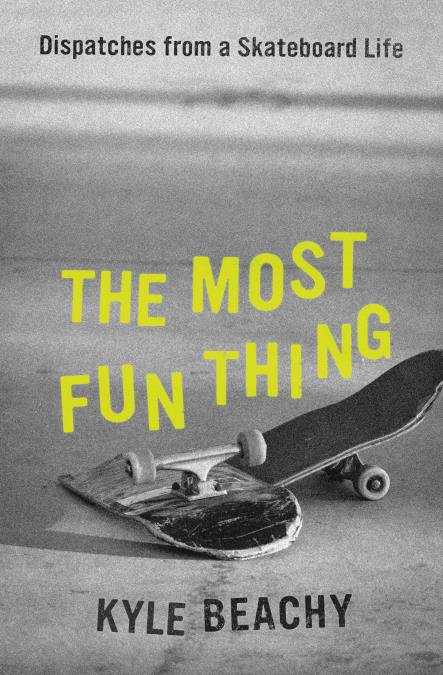

Kyle Beachy’s The Most Fun Thing is the first of its kind. It’s a book about skateboarding that views that activity as the springboard for broader conversations involving literature, commitment, marriage, and friendship. In many ways it’s a big idea book that at its core has only one idea, namely that we become ourselves only by constantly changing—and that such a process can be easier said than done.

Beachy is an Associate Professor of English/Creative Writing at Roosevelt University in Chicago and he skates every week. That’s important. In our interview I asked him about the literary namechecks and influences in The Most Fun Thing, why skateboarding alone isn’t really skateboarding, and cultural stereotype/subversion. Oh, and who his three favorite skaters are. You always gotta ask a skateboarder who their favorite skaters are.

Jeff Alessandrelli: One of the most engaging and intriguing aspects of The Most Fun Thing is your willingness to mix the personal, the non-skate specific personal, with what might very broadly be called skaterly shoptalk. You risk a lot in doing that, chiefly from skaters who might immediately check out when phrases like “committed marriage” or sentences like “Such, as we have seen, is the temporality by which skateboarding moves” appear. The breadth of the book represents one of its main strengths, but I’m curious if you felt or feel nervous about how wide-ranging The Most Fun Thing is. Do you have an ideal reader in mind for the book? Or?

Kyle Beachy: It’s simple but I wrote the book I wanted to read, one that stared into the weird and underdiscussed heart of this activity, this embodied practice, and didn’t look away no matter how baffling or conflicted the thing revealed itself to be. What I want from a book, any book, is a willingness to follow its object. And what regularly drives me so batty as a reader is when books seem to gesture toward such a project only to let off and retreat back to some clear through line rather than indulging whatever directions the thing leads.

Susan Sontag, William Faulkner, Lauren Oyler, Annie Dillard, Jorge Luis Borges, John Barth, Don DeLillo, Joan Didion, Edmund Husserl, Maggie Nelson, David Foster Wallace, Rebecca Solnit, Marilynne Robinson, Dan Beachy-Quick. And that’s probably less than half of the literary references namechecked and contextualized or grappled with during the course of The Most Fun Thing. At the same time as these references are appearing, however, and often in the very same essay, the reader is being introduced to relatively little-known skaters and videos like Randy Ploesser and St. Losers, Madars Apse and Cuatros. With everything small and large that happens in the book happening in the book was it hard to find the right balance? Did the fact that The Most Fun Thing was written over a period of ten years (right?) help in terms of finding a form and order for the book, or did the essays and attendant book sections congeal—to use a word I largely hate—organically?

These authors showed up because the chapter or essay benefited from the language or concepts that the author’s work brought to the consideration of skateboarding. Which, if you take a narrow definition of “skateboarding,” their inclusion will feel contrived. But the longer you stare into skateboarding the less choice you have but to embrace a broader definition of the term. The thing grows before your eyes, and soon to consider it means a consideration of embodiment, place, perception, crowds and individuals, space and time, basically all of the questions and tensions we associate with the humanities. So, then, the value of these specific skaters and videos that people may or may not have heard of is to yoke those broader concerns back to the activity per se. If there’s a balance, it’s a matter of opening and closing, backing and forthing. That, essentially, is the movement of skateboarding.

“But to skateboard alone is not fully to skateboard” is an assertion made in “On the Obvious,” the opening essay in the second section of the book, and it’s an assertion that I’ve lived. From the age of, say, 15, to the age of, say, 29, I skated 4 to 5 times a week, almost always with a friend or group of friends. Who those friends were changed throughout the years, but their existence kept me skating. Around the age of 30, though, I moved towns and this time I had no one to skate with…so, gradually and then suddenly, I stopped skating. (Or mostly stopped—I still have a board and go out every 2-3 months, almost always alone. But it’s a different version of skateboarding that I’m doing now, filled with ollie-less manuals and “cruising.”) I’m 37 now and it’s something I regret a lot. This is touched on in The Most Fun Thing a bit, but I wonder if you can briefly talk about why community is such an integral part of skating and skating’s interior culture. Is there something about the intrinsic act of skateboarding that brings like minded people together or is it more that the same is pretty much true for every sport? (I.e. the kid shooting hoops alone at the school down the street from my house would really rather be playing a pick up game, etc., etc.)

I believe it’s a different thing. At a basic level, we know that a kid shooting hoops alone isn’t playing basketball—they’re not defending or passing or blocking-out for rebounds, and certainly they’re not winning or losing the game. They’re doing something basketballish, but it’s not playing basketball. Furthermore, because the framework of sport, generally, is so central to our experience of each individual sport, we’ve come up with ways to cheat to accommodate fewer players, as with ghost runners in baseball, or adjusted rules for games of 2-on-2 basketball, and so on.

Such matters don’t translate to skateboarding. I go alone to the strip of well-paved street near my house and whatever physical things I do there, whether it’s simple ollies or flip tricks or silly little no-complies or whatever, is skateboarding. There’s no framework of sport activity that I’m lacking or approximating. These physical movements, this pushing and ollieing and falling, they are precisely what the framework of skateboarding demands. But as with our kid shooting hoops, something’s missing. The kid needs other players to qualify for the framework of sport and access the full breadth of activities (passing, defending, etc.) and competition (winning, losing).

Skate community is a matter of perception. Much of “skateboarding” is perceptual activity: seeing, understanding, comparing, mimicking. By extension, that means it’s also performative. Watch any video of someone landing their first kickflip and the first thing they do is beam to whoever’s nearby, often the person holding the camera. So, in addition to offering the things we expect from a community—company and mutual support and conversation—skateboarding requires community for the practices of watching and performing. It’s not just ego that compels lonely skaters to prop a phone up to film them. In a very real way, filming and sharing a clip fills in the missing pieces of skateboarding’s framework.

I initially read the first sentence of that last paragraph as “For the skater, community is a matter of precision” and it simultaneously threw me for a loop and seemed entirely fitting. Because for both writers and skateboarders precision is such an important thing. Beginning writers sometimes push against this, as they’re more focused on feeling and raw emotion, but the further one tunnels down the more it becomes apparent that the surface level emotions are really only conduits for deeper modes of feeling and belief. And for skaters the word “sloppy” is normally code for redo, even if it was a make. Do you embrace skating-writing analogies or bristle against them? I’m curious too how in a classroom setting your background as a skater manifests itself. How do you navigate such broad, far-flung topics as voice and style and genre? Directly or indirectly each seems to have a corollary in skating. (I.e. voice=persona, style= style and genre=preferred terrain.)

I don’t bristle. For me there’s just so much that’s different between the two practices that I don’t make my relationship to skateboard aesthetics overt in my pedagogy. I do believe—and this is a big thing that the book is trying to say—that style and form are inseparable from meaning. This informs my course design and reading lists and the ways that language is always, always centered in workshop. I’m far more attentive to syntax than story arcs, and the only real way I can address plot is to talk about energies and surprise. I encourage playfulness.

In the essay “On Narrative” you state “…much of my desire to write about skateboarding has grown from my own lack, which in turn has affected the ways I perceive the activity, along with its films. We are always, after all, looking for what we want.” You later go on to opine: “One way to define a poem might be: a poem is the opposite of a brand.” As a mostly non-narrative writing poet, I loved this assertion. I’m interested, though, in how your own brand (for better or worse) as a professor/skateboarder has impacted academia’s treatment of you as you’ve both continued to teach and continued to skate. A lot of people still equate active skateboarders with adolescence, even if that view is stereotypical. Have you ever felt the need to explain your passion to your colleagues and/or higher ups? And on the flipside, as a tenured professor have you ever felt misjudged or inaccurately portrayed by members of the skate media?

I’m not really trying to test the limits of the two worlds overlapping—I’d never squeeze in a quick session then stash my board before class. I suppose I do dress a bit more casually than my colleagues, I wear Vans and my pants are definitely baggier. But, you know, skaters are sneaks. I get joy from being a little out of place. As for how skaters see me, I mean it takes all of ten or eleven seconds of looking to tell whether someone actually rides the thing with regularity. And I do. I push around the neighborhood, I ride the train downtown, I bike to the spot at the high school, I get into cars with my crew and go on road trips. I will admit that, yeah, part of sharing clips on social media is proving a bit for anyone who might wonder. I’m not particularly good, but I am in fact out there doing the thing. As long as I’m doing it, I could really care fuck-all what members of skate-media might have to say. That’s I guess one big difference between skating and writing.

I tore the below out of an issue of Thrasher in the mid-90’s and ever since then it’s been hanging up on one of my (various) living space walls. When I was skating regularly it probably meant less to me than it does now, but regardless I think it’s a powerful image/ sentiment. When you see the below what immediately comes to mind? “Skateboarding Is A State of Mind”–agree? Disagree? Something else entirely?

Agree, yeah. A state of mind that shapes perception of the world around us and works reflexively to inform our embodied navigation of space and time. So, a state of mind that relies on and is inseparable from a state of body. And this is why a phenomenological approach to selfhood, an intentional consciousness, is so useful to understanding skateboarding. To someone like Maurice Merleau-Ponty, to exist is to be a body thrown into the world and asked to perceive, respond to, and inhabit that world. One is never finished with our work of existence, the activity of becoming. Hubert Dreyfus speaks of selfhood and coping skills, by which “my experience with things shows up in the look of the thing.” The more the self learns, the more nuanced and detailed that self’s perceptions and skills, which in turn make the world look richer with possibility for action. “My knowledge isn’t in me,” says Dreyfus, “my knowledge of the chair is in the increasing richness…of my encounter with the chair.” That, more or less, is the stuff of skateboarding. I’ll add that it’s wildly disorienting to see Gonz wearing DC shoes, like some kind of violation. I love it.

Entitled “The Dylan Period” one of the last essays in the volume touches on the late great pro skateboarder Dylan Rieder. At the beginning of the essay you break down a “number of models and metaphors for time,” specifically chronos, aeons, and kairos. Although I’m interested in your take on Rieder’s too-short life and career, encountering these time-based notions at the end of The Most Fun Thing made clear to me how much this book is really about time—past, present, and future. When you started writing the book in 2010 skateboarding was in a very different place as compared to now. At this point what do you think the future of skating looks like? I know in recent press for The Most Fun Thing you’ve lamented that to certain mainstream populations skating still seems to be stuck in stoner/loser stereotype and cliche. If in the next ten years it completely outgrows that misperception, what do you think things will look like in, say, 2032? With so many disparate pockets and communities everywhere—from backyard DIY parks in one corner to Olympic training facilities in another—will skating still be recognizable in the way it currently is today in your opinion? Or are big changes potentially looming?

Oh, it’s always changing and always about to change. None of it’s linear, but there are definitely two distinct vectors of change. The first is the Dylan Reider sort that comes as a result of skateboarding’s geist, and includes the people, programs, institutions, and brands that emerge from within the world of skateboarding, who have been shaped by skateboarding and, as such, trained to push against edges and borders, including skateboarding’s own. Dylan changed skateboarding by dressing and moving in ways that made skaters uncomfortable, but there was something uncanny in it, something spiritual that skaters couldn’t help but recognize. So, the more geographically and biographically diverse the skaters who are doing it, the more certain the changes that’ll come from within.

The second type is the change that comes from people who see skateboarding as having some use-value, as a tool to leverage into financial or political ends. But here’s where that first vector of change, skateboarding’s protean nature, becomes so vital. Because no matter how many training academies get built, there will always be a contingent that’s directly and vociferously opposed to state-sponsored competition. So, I guess my sense is that we’ll see changes from lumber shortages that lead to new ways of pressing boards, but the spirit of skateboarding is essentially what it is.

What’s next? At this point have you been satisfied with the initial reception of The Most Fun Thing? How is your relationship with your wife K and is your long-gestating novel about skateboarding still happening or not so much? Finally and most importantly—this ages me, but my favorite skaters are Bobby Puleo, Ethan Fowler and Clyde Singleton. I’m sure you have multiple, but if forced to pick your top 3 (at least at the time you read this question) who would you go with?

I have a buddy who’s put out a bunch of brilliant rap albums with different labels. He describes promotion cycles this way: It’s never enough and then it’s over. I’ve been fortunate to have some great conversations come from this book’s existence. K and I are married and good to each other. I’m working on the novel again, yeah, curious how the draft will look now that it’s liberated from the considerable burden of saying something about skateboarding. As for top three, right this second I’d say Nick Matthews, Mark Suciu, and my friend Ted Schmitz. At least two of those would change if you asked me again.

New work by Jeff Alessandrelli appears or is forthcoming in BOMB, Poetry London, PANK, The American Poetry Review and Gulf Coast. The Kenyon Review called his most recent poetry collection Fur Not Light (2019) “an example of radical humility,” and, entitled Nothing of the Month Club, the UK press Broken Sleep released an expanded version of Fur Not Light in June 2021.

In addition to his writing work Alessandrelli also directs the non-profit record label/book press Fonograf Editions. He’s at https://jeffalessandrelli.net/

This post may contain affiliate links.