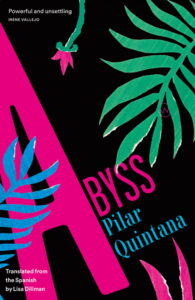

[World Editions; 2023]

Tr. from the Spanish by Lisa Dillman

The rigidity of gender roles has been an ongoing point of cultural contention internationally. Pilar Quintana takes up this issue in her newest work, Abyss, translated by Lisa Dillman. Set in Cali, Colombia, Abyss follows an eight-year-old girl, Claudia, as she navigates roughly a year of her life, when it is disrupted suddenly and violently. Quintana conveys the phenomenological experience of childhood through understatement, especially when handling charged themes of gendered expectations, suicide, and mental illness.

We are immediately dropped into the abstract as Claudia tells us about her family and history. Describing a moment that hurt her mother, she offers a clue about Abyss’s key theme:

One time, at the club, mamá heard a woman ask my grandmother why she hadn’t had more children.

“Ay, mija,” my grandmother said, “If I could have avoided it, I wouldn’t even have had this one.”

Namely, it is abandonment or the feeling that your existence doesn’t matter at all. A pernicious tone radiates from the text as the narrative moves along. The abyss only grows.

In this empty space, expectations of marriage imprison Claudia’s mother. Claudia tells us when her parents were courting, her mother’s elders coaxed her into it. “‘If you spend your life finding fault with every man you meet, you’ll end up alone.’ My grandmother and the other women nodded, staring at mamá. That terrible heat, I felt it, like a rope around her neck.” Similarly, in other moments, women are forced into becoming wives lest they lose their worth and purpose. A woman making it on her own isn’t common in the world Claudia inhabits. She is protected from this truth by her age, but the small hints that she doesn’t think about stand out to the reader because what Quintana doesn’t state directly shouts at us.

When Claudia’s aunt marries a much younger man, Gonzolo, the issue of what Claudia understands, but does not explicitly say comes to the fore. Claudia’s mother is bored of her husband. They married when she was young. “Jorge, I’m twenty-eight and you’re forty-nine.” It isn’t long before Gonzolo begins to rendezvous with her mother with Claudia in tow. The significance is entirely lost on her, but we can pick up on the undercurrent. This isn’t to say that as an eight-year-old, she doesn’t know what’s going on, but more that she doesn’t know the specifics. This chipping away of innocence is another element that Quintana builds throughout Abyss, showing how it can occur over time and isn’t the sudden shock that some experience. “He hardly noticed I was there or even said hi to me . . . He got so close when talking to her that it was impossible for me to hear, and if he paid any attention to me it was just to make sure I wasn’t touching anything.” Predictably, her mother becomes protective of this connection at the price of her own relationship with Claudia. The mother’s guilt is palpable. She sacrifices her role as a mother in order to fulfill this fantasy and impulsive desire that overrides her otherwise rational portrayal.

Inevitably, this relationship is short-lived, and it damages the family’s equilibrium. Claudia’s mother becomes depressed and remains in bed for weeks, only emerging to eat meager meals and leaving Claudia to her own devices. There is a moment when Claudia brings home a portrait of her mother she has been spending weeks on, only to have her mother brush her off, “Claudia, I just took my allergy medicine, I’m sleepy. Can you show me later?” Her father sleeps in his office for a time but otherwise continues working at the supermarket he owns. In the meantime, Claudia attaches her insecurities and companionship to a doll named Paulina that her aunt gave her. She tries to navigate school and even shows her family the work she has done, including a portrait of her mother. Yet, she only receives rejection. Instead, her mother responds with the stories of Natalie Wood and Karen Carpenter, who, according to her, died of their own accord. Claudia is unsure how to take either story, other than that her mother seems to respect them for taking control of their fate. Of Wood: “Everybody thought the husband had actually found her in the cabin and, jealous of Christopher Walken, had a fight with her and threw her overboard. Everybody but mamá. ‘She jumped overboard herself.’” Of Carpenter: “They found her in a closet, naked, though she’d covered herself with the pajamas she had just taken off to get dressed. Even in death, she behaved like a decent senorita.” In Claudia’s mother’s perspective, men are mere functionaries of the system that keeps women trapped in their states in life, and suicide may seem the only way out.

The abyss also becomes a physical reality for Claudia. The connection is clear when her mother’s last remaining relative, a second cousin, falls from the balcony of her eighteenth-floor apartment. It is believed that it was an accident. Claudia’s mother states that her cousin was watering plants on the balcony and lost her balance on a bench. Yet, what remains with Claudia herself is the thought of plunging through the air. The conflict of suicide with Catholic moral teaching, which is deeply entrenched in Colombian society and culture, may account for the pressure to avoid discussing the cousin’s depression. While Claudia and her family are not particularly religious, the societal pressure toward silence fits with the novel’s emphasis on understatement and brevity.

In another notable scene, Claudia quite certainly saves her mother, who seems to at least be contemplating suicide. They are vacationing in the mountains at a family friend’s house, which sits on a cliff, and part of the fence is precariously weak and borders the edge. This is where Claudia finds her in the middle of the night.

“What are you doing?”

“I just came out for a walk.”

In the middle of the night, barefoot and in pajamas, like Natalie Wood . . . Then I saw it in her eyes. The abyss inside her, just like it was in all of the dead women . . . a bottomless pit that nothing could fill.

“This is the perfect place to disappear.”

“Let’s go,” I said, and pulled her.

The careful, soft touch that is written into Claudia’s words is heartfelt and carefully chosen. There isn’t panic behind them, only a quiet recognition of her mother’s condition and the single purpose to keep her safe. The connections that she makes to Wood and the others her mother has discussed point to how children truly listen and hold on to things long after adults have moved on. By contrast, Claudia can’t move on because these early experiences are formative for her.

It is commendable how Quintana conveys all of these threads through the eyes of an eight-year-old. She strips away the illusions that parents hold that they can just “cloak” their language or argue behind closed doors. Children see through it. They always have, despite good intentions. Even if something isn’t entirely understood, there is an inkling that it is either right or wrong, because that is how children see the world, at least in varying degrees. The danger of silence and lack of communication, ironically, speaks volumes, since Claudia bridges the gap between her mother and father. How often do parents ignore the impact of their actions on their children? Even the most mild of unconscious actions, such as the mother’s oversleeping or the father’s obtuse silence, informs Claudia of her behavior and worth. Much is owed to Dillman’s excellent translation and careful word choice, which keeps the language as simple and child-like as possible without dulling the power of the narrative. Abyss is a beautiful, brief story that attempts to show how children are often the only way for us to notice what is important.

Alexander Pyles is a writer, editor, and critic based in the Chicagoland area. He holds an MA in Philosophy and an MFA in Writing Popular Fiction. His chapbook MILO (01001101 01101001 01101100 01101111) was published by Radix Media as part of their award-winning Futures series. His nonfiction has appeared in the Chicago Review of Books, On the Seawall, Litreactor Magazine, Analog Science Fact & Fiction Magazine, Ancillary Review of Books, and others.

This post may contain affiliate links.