[Archipelago Books; 2020]

“Remember to write the life story of Dr. T” is the instructive title of one of eleven “case studies” comprising The Loss Library by Pretorian author Ivan Vladislavić. This particular case study, from 1998, testifies the dilemma of being entrusted with other people’s archives, touching on the case of a pseudonymed Louis Fehler, who left his papers to Vladislavić before travelling “and then promptly died,” as well as the case of Dr. T, whose trunks of papers Vladislavić took on only to discover narrative chaos of both Dr. T and his father. He convinces us in the span of a few pages about the terror and dismay of archiving the life of another, a task of endless beginnings and shape smudging, gluttonous in its occupation of physical and mental space. “Over the years they have been in my possession, I have developed a rapport with the trunks,” he writes, “less as repositories of evidence than as objects interesting and valuable in themselves, and this may well be the key to completing the task.”

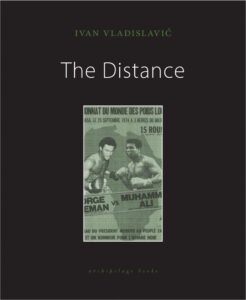

Years later, Vladislavić revisits this quandry in his latest novel, The Distance, where the Blahavić brothers, Joe and Branko, try to write a memoir about their Pretorian childhood — one heavily defined by Muhammad Ali — forty years on using Joe’s paper archive on Ali. Joe, the writer, appears as the key memoirist, writing about his obsession with Ali, but Branko, whom we also learn is a writer despite his protestations, keeps time with his brother, writing about Joe writing about Ali. Their childhood memories are supposed to be carved up between them along these borders but as Branko observes, “My brother wants me to tell his story. Or is it mine? Ours? Can a story ever belong equally to two people?”

The novel is narrated in juxtaposed fragments by the brothers, the polyvocality resulting in — or producing, perhaps — a harmonizing tone for a fraternal relationship that isn’t always harmonious. The language is shared, even if their worldviews and memories are not, a fated sonic alignment not unlike the lyric sound that Ali developed in speech and body. Float like a butterfly/Sting like a bee. At a press a conference, referring to his first fight with Joe Frazier and the all-white judging panel and referee: I know I have the wrong complexion to get the right connection and the right protection. “Proto-rap,” as Joe notes. Before the 1971 fight against Buster Mathis, Ali revealed, “I’ve developed a new punch. I found it during my fight here against Jimmy Ellis four months ago. It’s a half-chop right hand and it dazed Ellis.” Joe mentions this incident, writing: “He found it, the way a painter might find a new method of applying paint to the canvas or a guitarist a new tuning for his instrument.” The two brothers sound different, but they are brothers, and Vladislavić’s prose is elegant in its insistence on this. He wields images like soft cloth; the memory of their impressions is lasting. It works. The constant leaps from loving accounts of Ali’s boxing art to childhood recollections about mundanities like their mother’s scissors or marble games come to feel inevitable. This is the real strength of the novel, its ability to convince us that our childhood is tethered to us in powerful, unfinished ways. That sticker on the cupboard in our mind’s eye, the intimacy with which we narrate the successes of the sportspersons or astronauts we love, the way a fabric from home felt under our fingertips. The ability to summon all this from a paper clipping decades later without knowing what to do with it: what does it mean? “The gap between how things are and how they appear to be doesn’t seem to bother him,” Branko writes of his brother.

He is talking in the context of social norms, not memory, but the two are intertwined across Vladislavić’s novels and especially in The Distance where Muhammad Ali’s blackness shapes the politics of the two white brothers during Apartheid. Vladislavić’s characters confront their whiteness and its violence relentlessly and confusedly, across multiple contexts: in school, parenting, gentrification, and even in the architecture of their own homes. There is no liberal trick in this exposure; the revelation only serves to point to the deep rootedness of white acceptance of segregation. “Maybe there are things we can’t talk about and the retelling only redoubles the insult,” Branko thinks. Vladislavić is attentive to the perniciousness of whiteness in how it determines the terms of “ordinary” life in South Africa, like the pervasiveness of “servants’ quarters” in suburban houses. And so Joe’s adoration of Ali can never be just a naïve childhood infatuation but is that of a white boy’s love for a Black man, the Greatest. Joe’s love for Ali is not a signifier of his anti-racism or his commitment to integration, and is frequently absurd and petulant. As a teenage boy, he identifies with and longs for Ali’s resistance to power structures, but also holds his love in secret. As a grown man, he looks at his archive of Ali clippings and we learn with him how tender yet careful his love was. The novel commits to remembering the strain of this love: it is not easy, or straightforward in how it tendrils Joe and Branko’s adult memories of that time. This love is hesitant, racialized. In attempting to account for it in retrospect, the characters edify their whiteness. Over the course of arguing over whether they — the brothers — are writing a memoir about Ali or their lives, the novel produced by Vladislavić is, of course, about both.

It is fitting. Vladislavić, refreshingly, is not a sentimentalist. His interest in the potential of the fragment as a form of fiction that bears witness to political truth, is ever yielding. The fragment is an episode, a memory. In Vladislavić’s novel The Restless Supermarket, it appears as corrected corrigenda in a nested text called “The Proofreader’s Derby,” written by an affected conservative proofreader who proofread telephone directories “for the regime,” as he is told. In The Exploded View, the fragment is a redrafted questionnaire for the national census in the post-Apartheid era. Elsewhere, the fragment is an enclosure in a letter, like in his moving novel Double Negative:

A recipe for breyani, which I’d mentioned in my last letter. A Polaroid of Paulina at the wheel of my old Datsun, the hand-me-down car, on the day she got her driver’s license. A shopping list she’d found in the bottom of a basket at the Hypermarket: mealie meal, pilchards, sticky tape, Doom — with the last item crossed out. Occasionally, a cutting from the newspaper, some small story most people would have read past.

Vladislavić’s talent for trailing his obsessions across multiple works is rewarding because these obsessions morph in form as they travel, retaining a sense of their idiosyncrasies. It’s fair to say that Vladislavić is preoccupied with language, memory, and cities, but it’s truer to say that his obsessions are more precise and delightful: lists, idioms, wordplay, the everyday decay of cities, descriptions of art-making, boxing, recurring characters, photography. This chrysalis act is evident in how Vladislavić uses the form of the fragment too; a modernist legacy that he wears lightly. The small story from the newspaper that is remarked as going unnoticed in Double Negative, for instance, expands into chapter epigraphs in The Distance, featuring snippets from the story on the back of the Ali news clipping. These shards of image or text are not substitutes for fiction, but supplements, and in several cases, fiction itself. They position memory as no more or less than a moment that disappears as soon as it is captured materially, leaving behind the fragment as an approximation of what may have been.

Is an approximation of memory enough to keep documenting life or writing about it? The Distance jabs at this question repeatedly. The two brothers remember their lives distinctly from each other. Branko senses he is missing from Joe’s fragmented notes, while Joe cannot seem to remember his childhood outside of Ali’s orbit. They even remember the same objects of their childhood differently: Branko describes their mother’s sewing scissors as objects with a life of their own, “meant for nothing but silk and satin. They’re supposed to fall through chiffon like a hot knife through butter.” Joe sees them as yet another piece of the archive, writing that “they lay on a patch of velvet like a museum exhibit. Handicrafts of the ancients.”

In Double Negative, Neville Lister, the photographer protagonist, thumbing through dead, stolen letters wonders, “How can I say what these fragments mean to me? The awkward truths of my life take shape in their negative spaces. In the lengthening shadows of the official histories, looming like triumphal arches over every small, messy life, these scraps saved from the onrush of the ordinary are the last signs I can bring myself to consult.” An evolution of this sentiment is glimpsed in The Distance too, as one that determines the dramatic question of the novel, and its form. Vladislavić is a poet of the fragment, stylish and honest in his fictions of memory. “Remember to write the life story of Dr. T,” as he wrote, is a reminder to us all about the fictive potential of the archival trunks we hold for others, and ourselves.

Sharanya teaches and writes in west London.

This post may contain affiliate links.