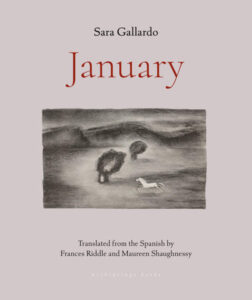

[Archipelago; 2023]

Tr. from the Spanish by Maureen Shaughnessy and Frances Riddle

Nefer, the teenage protagonist of the slim, classic Argentine novel January, first published in 1958, is pregnant and doesn’t want to be. We learn so in the first sentence of the novel. The second begins: “Everyone here and everywhere else will know by then . . .”—then being the next harvest.

We are taken back to the night “where all her troubles began.” Nefer is in love with a local man, a gaucho, a cowboy known as Negro. Gallardo perfectly captures adolescent love, its obsessive, intensely emotional aspect. Her love for Negro looms large, as does her intense jealousy of other, wealthier girls. She must work the wedding party where Negro is a guest, “serving guests . . . the heat, the coals throbbing in the dirt next to the spits dripping fat, the men bending over to slowly carve the meat.” Despite the labor, she had bought fabric to make a new, lovely dress, a “floral fabric because she thought Negro would like it.” As she serves the guests, “Nefer . . . had eyes in the back of her head, up and down her arms, her neck, all over her body. Without looking at him directly, she could see Negro the whole time.”

She is dismayed, despite her obsession. Love is hope, and everything that gets in the way of its consummation threatens Nefer. She thinks: “If only her nails had not been worn down to nubs from working . . . if instead she had been someone else, she would have ripped Delia’s face to shreds.” The rage she has for Delia, a “shop owner’s daughter,” is extreme. While Delia sits right next to Negro, Nefer daydreams of burning her in the fire, and feeding “her ashes to the caracaras, to the dogs, to the possums, to the foxes.”

Adults often dismiss the emotional state of the young. Gallardo does not. Nor does she shy away from class. Having money or not defines the power of the living, a close second to the dearth of power from being born female. These facts are beautifully woven throughout the novel. They are the main subject matter, which shape Nefer’s experience of love and personal agency.

After Nefer’s rage and jealousy of Delia grows unbearable, Nefer thinks her own “soul is black. A soul like the fields in a storm, without a single ray of light.” She runs off, escaping the festivities. At her most vulnerable, alone in the night, crushed with lovesickness, she runs into a man named Nicolas, a railroad worker, “an enormous man” who “stands in her path.” It is then that she is raped.

The word rape isn’t used in the book. In 1958, rape was not used as it is now, or defined as it is now. And yet. So few things have changed. The actual incident is described in one short paragraph and preceded with Nefer thinking, “She could’ve just as easily said no.” While Nicolas rapes her, she thinks, “Negro is with Delia, the man is sweaty, it’s hot. I’m suffocating. Oh Negro, Negro, what have you done to me? Look at my dress, it was supposed to be for you. . . ”

Reading this passage now, around seventy years after it was published, is astounding. Nefer is a child. All over this planet, to this day, female children are given to older men. Recently, in England, the age of consent, which is sixteen, is being discussed. What astounds me is how little things have changed. And yet, considering Nefer’s interiority, what she wishes is that she were with her love, Negro. To me, this is brilliant. She is not without sexual yearning, but she is still being raped. This debunks the idea of innocence. But it doesn’t matter. Nefer is raped. The idea that there is no shame in a girl having sexual desires is as modern as the idea that rape is a crime.

Since the dawn of time, women have been property first, which means rape didn’t exist. You can’t rape some “thing,” an object that you own. New DNA shows that mankind is born of rape, so maybe Andrea Dworkin wasn’t totally bonkers when she said all heterosexual intercourse is rape. Historically, this has accuracy. When I was eighteen, in an Evolutionary Theory 101 class, we watched the movie Quest for Fire. I mention this for levity, but also because there is truth in it. In the class, my eighteen-year-old feminist self commented on the rape. My professor, a brilliant woman who I worshipped, said something to the extent that rape didn’t exist then. I was stunned.

At the end of Quest for Fire, mankind advances by harnessing an aspect of nature, fire, and spoiler alert, the woman gets on top during sex. At this point in American history, we have men trying to get to Mars, and women still can’t get abortions. I don’t see this as strange. For people to have power, and to keep power, they must have it over something. Over the universe, over the female body, over the less powerful. I have no answer to this problem.

Nefer herself looks for answers to her problem with her witch doctor paternal grandmother whom she has never met. To do so is terrifying. To face terror is brave. She leaves in the scorching, suffocating midday heat when her family and her community is in siesta, hoping not to run into anyone. It is an hour ride. As Nefer reflects, “She doesn’t want to think about the end of her journey, about the old lady she’s never seen but with whom all her hope lies.” As she approaches the homestead, exhausted and thirsty, not well (she has morning sickness), she runs into her male cousins, who know exactly why she is there. They torment her by singing, “gotta ride on horseback when you’re a whore, when you’re a whore and a slut, on horseback, yeah.”

There is so much beauty in this story—the beauty of countryside, the beauty of clothes, and horses and food. Certain aspects of translation make for a fuller immersion in the rural culture—my favorite word often used in the novel being the word “Goodandyou,” which isn’t a word in English, but is in this book, to be true to the specific Argentine dialect. The “old lady” knows why she is here. Nefer takes mate and drinks. She and her horse are exhausted. Nefer thinks: “After this mate. I’m going to get up and say goodbye.” And she does. As she leaves, the old lady follows her, saying, “You don’t want anything from me? You don’t need anything? . . . Something . . . ?”

“Once back on her horse, she almost feels like she’s home.” Home. What a word. A place of comfort, belonging. What happens next? Did she avoid a horrific death by not attempting an abortion? Possibly. Is this a story of how poor, rural women had few choices in life, none of them great, many of them dangerous? Absolutely. Gallardo was from the elite, wealthy Argentine class and her family, Tolstoy-like in the 1950s, lorded over “extensive agricultural property.” Can we trust Gallardo’s take on the interiority of a poor child, raped and pregnant with no recourse? Nefer knows that her poverty is one of the reasons she has so few options. When the vast majority of a country cannot speak for themselves, their only chance is to be seen and heard by someone who has a voice. Gallardo is that voice.

January is a story about rape and abortion, and yet there is the beauty of the land and its inhabitants, however unfortunate. The point of view changes with ease, something American writers are basically not allowed to do. Once in church, we hear Negro’s thoughts. It’s a simple moment: “The priest stops, takes a handkerchief from his sleeve and blows his nose. Negro thinks he would lose anything he tried to keep tucked into a sleeve like that.” There are descriptions of the land that make me yearn for the countryside. Of import is Nefer thinking, “Before, when she was happy—she now knows that she had been happy before—her eyes would wander far away, from the tree line to the wind pump to a herd of horses in the distance, a buggy on the road.”

January, for all its political relevance, is also a wonderfully paced story. Every story has a clock, to paraphrase E. M. Forster, and Gallardo has that, as well as complicated, well-drawn characters. I add this here at the end of my take, because suffering can be seen so well if we place it in the world, which has so much more to offer than misery.

Paula Bomer is the author of two novels, Nine Months and Tante Eva, the story collections Baby and Inside Madeleine, and the essay collection Mystery and Mortality. Her work can be found in Volume 1 Brooklyn, The Cut, LARB, New York Tyrant, Juked, The Literary Review, and elsewhere. Her new novel, The Stalker, will be published by Soho Press in 2025.

This post may contain affiliate links.