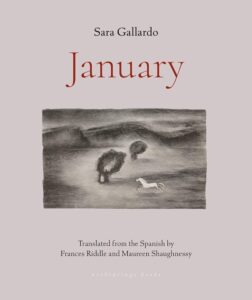

[Archipelago; 2023]

Tr. from the Spanish by Maureen Shaughnessy and Frances Riddle

Lapwings are a type of bird with a flicking style of flight and a shrill cry. They populate Sara Gallardo’s 1958 novel January from beginning to end; they are ominous each time they are perceived by protagonist Nefer in the scorching summer skies of an Argentine January. They are equally foreboding when compared with a meddling and overbearing ranch patrona and with the cursed son of a “witchdoctor” that Nefer visits in hopes of ending her secret and unwanted pregnancy. Lapwings gather, accruing the gruesomeness of vultures, though it turns out their only malevolent trait is their feigning of injury when scared. The collective noun for a group of these birds is a “deceit” of lapwings. Ditto the original Spanish: “un engaño de avefrías.” Deceit, Gallardo implies here in her stunningly economical prose, does not originate in the individual act of hiding a pregnancy, but in the collective act of condemning a woman to gestate one in secret dread.

Dread may be at the forefront, but this is no gothic horror; it is a tragic and precise condemnation of systems. The specific tragedy of this novel is that teenaged Nefer is raped at her sister’s wedding and is ultimately sent off to wed the rapist. The more cosmic tragedy lies in the oppressiveness of the way society (even in a rural outpost, especially in a rural outpost) has warped Nefer’s despair and misdirected her rage.

The book opens and closes with a dread of the harvest, which serves as both timekeeper and truth teller about the pregnancy. “Everyone here and everyone else will know by then.” In fact, Nefer treats time itself with disgust, as she reflects that “days are yoked together, come and go like an endless herd tramping through the gate.” Agricultural time becomes shorthand for an enemy, the antagonistic force that she cannot quite articulate lies within the landowners who keep Nefer’s tenant farmer family in line, with the priest and doctor who condescend, with the railroad man Nicolás who has casually assaulted her. Only an understated half a page acknowledges the circumstances of Nefer’s rape and impregnation.

Her rage, though, both within the moment of the rape and otherwise through the rest of the book is directed at another woman, Delia, whom Negro, the object of her adulation, has asked to dance. Nefer wishes that Delia would become stuck in a tree and starve; she wishes she would drown. In a moment of rage against this competitor, Nefer boils: “Like a pale scar that suddenly burns with exertion, her grandmother’s blood flared up in her veins. Nefer had barely known the woman and yet she lived on inside her . . . the dark skinned grandmother who died at the age of one hundred without a hint of gray, terrifying wisdom in her words.” This is the sole mention of her Indigenous grandmother, but Nefer’s identification with her is at once stressed and vilified. Her self-hatred runs as deep as the colonial attitudes and systems that Gallardo interrogates throughout the book.

Nefer hates her sisters too, along with any other woman who was lucky enough to avoid a fate like her own. She seethes as her mother panders to the patronas, and despairs when the old grandmother of a witch doctor she visits simply says “have it your way,” dismissing her coolly when she loses her nerve to ask for an abortion. At the critical moment when she finally admits the pregnancy to her family (Nefer blurts it as her sister and mother force fried buñuelos on her “too skinny” but completely nauseous body), a horseracing report plays in the background. Gallardo is an economical writer; the women are all in a betting race.

But the question is, why does Nefer seethe at the women around her and pay no mind to her rapist? The simpler answer might be trauma, though Nefer’s perception and understanding of the men around her is a rich territory into which Gallardo delves. One of the most heartbreaking moments in the book is directly after Nefer reveals her pregnancy at home; it is not when her mother hits her and calls her a hussy, or when her sister shows herself simultaneously dismissive and jealous, but when Nefer looks at her father, silent and distracted with his leather-braiding hobby: “thinking of him is like dimming the lights, pulling the sheets over her head, and finally feeling at peace.” This does not reveal any type of close relationship she has with him; rather, his distance, his position above the concerns of womanhood make the space of privilege she admires, and where she feels at peace.

She fetishizes the time and space to practice guitar (even badly!), as she imagines herself in the place of a male worker who boards with the family. Watching Negro attach coins to his belt, Nefer remembers that as “a little girl she wanted to be a man, to be able to flaunt such glittery finery at parties.” We get an even better sense of these desires when, for just a moment during mass, Gallardo switches the third-person perspective with which she has been closely following Nefer to settle into Negro’s thoughts. He thinks of a woman that is neither Nefer nor Delia. He considers some musicians and their talent, the priest and his decadent robes. He is not threatened by the talent or awed by the priest, just simply bemused, wondering idly if the priest keeps tissues in his vestment sleeves. The perception roams for a moment to the father’s head as well—he simply notices that his wife resembles an owl—but the effect is to remind the reader of the simplicity and transparency that men are allowed. Every act need not be reactive.

But reactivity feels like the sole protection allotted to women. As soon as the mother, on leaving the doctor’s office with Nefer, states, “It will all be taken care of tomorrow,” implying the possibility of a much-desired abortion, the entire pregnancy is reframed for Nefer. “She feels as if the enemy shadowing her night and day has become a secret ally.” The secret source of power exhilarates her briefly. She tells her mother, “Nobody’s going to lay a finger on me.” She looks at her reflection in the mirror and smiles. When her mother holds her to the declaration, the “secret ally” becomes a “silent friend.” Its purity and strength went unappreciated, but when discovered becomes, like appearance, just another currency of womanhood. Then part of the burden again. Like the blood of her Indigenous grandmother, which she yearns for and shuns, she does not know if she gets power from channeling or suppressing it. Everything that is hers is yet another opportunity for self-hatred, especially when beheld in the eyes of other women.

One of the most intriguing mysteries that Gallardo plants in this tone poem of a novel is how and why a young girl living in an oppressive colonial society might have ended up with a name of Ancient Egyptian origin. The unlikely triangle—or trinity—of Nefer, Negro, and Nicolás pulls a lot of weight in this book. Nefer, with her pre-Christian name, longs for the gaucho Negro, whose race remains undisclosed. But she is subsumed two times, in rape and marriage, by the “enormous,” “laughing” Nicolás, who takes sugar in his mate and proclaims himself “no countryman” and is surprised to find himself marrying a “dark, skinny one” when his preference is for “big blondes.” He is jolly about the marriage even though it is implied that the patrona forced it. He is a colonial import and a sinister Saint Nicholas, showing up late—the book takes place around epiphany—and contradicting the existence of wise men. In the book’s final lines, Nefer mirrors Nicolás’s bemused helplessness: “The harvest. From here on out I’ll be a married woman when the harvest comes.” Her mother falls asleep. If misplaced rage and resignation are Nefer’s coping mechanisms against the abuses of sexism and colonialism, then writing complex characters and subtle allegory are Gallardo’s.

Abby Walthausen lives in Los Angeles where she writes (often about books in translation) and teaches (often about vermicompost).

This post may contain affiliate links.