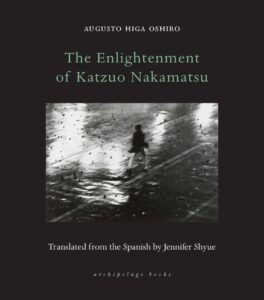

[Archipelago Books; 2023]

Tr. from the Spanish by Jennifer Shyue

In The Enlightenment of Katzuo Nakamatsu, the titular protagonist is having lunch in a Japanese restaurant—enjoying an Okinawan soup reminiscent both of his parents’ place of origin as well as of a lost Lima, and Peru, of the 1950s—when gunfire in the street brings him back to his current, alien world. He looks at the body, a young victim of gang violence covered by newspaper, and is struck by the lack of pity he feels, for “at the end of the day, the boy wasn’t one of his dead or in his likeness, nor the extension of his body, nor of his blood, his eyes, his race. Perhaps he wasn’t even a citizen.” The moment underscores how Katzuo himself has no belonging: As a second-generation Japanese-Peruvian, he’s “almost a foreigner.” This strange status is patiently explored in its many dimensions in this singular novel by Augusto Higa Oshiro, the first of his to be translated into English.

Higa Oshiro’s novella was published in 2008, and reissued in 2015 by the Japanese Peruvian Association, a century-old cultural institution based in Lima. This second edition has now been translated into English by Jennifer Shyue, with an afterword by her that supplies basic facts about the author, who died in April of this year. There were two phases to Higa Oshiro’s literary career, she writes. “The story collection Que te coma el tigre [Let the tiger eat you, 1977] was his first published book and is emblematic of the first phase, in which his fiction rarely moved outside the neighborhoods of his childhood in Lima’s working-class historic center.” He spent this period affiliated with the Grupo Narración, a collective of writers in Lima who had emerged in the mid-1960s, inspired by the literary legacy of the great Peruvian socialist José Carlos Mariátegui. “In the early 1990s,” Shyue continues, “Higa spent a year and a half as a dekasegi [a short-term migrant laborer] doing factory work in Japan. His subsequent return to Peru marked the beginning of the second phase.” Higa Oshiro’s second phase of work was concerned with the experience of the Japanese immigrants and Peruvians of Japanese descent, known as the Nikkei people. Enlightenment, a rich and enigmatic little book, fits squarely within this second period.

According to Shyue, Higa Oshiro spoke “deliberately, unhurriedly” when she met him. In his fiction he formulated sentences that were “elliptical, often anaphoric, building to a swaying rhythm that slips by like silk and is likewise slippery to pin down in a new language.” Nevertheless, Shyue has precisely captured this steady, stately drift of Higa Oshiro’s prose, reflecting the protagonist Katzuo Nakamatsu’s inner world of zen-like disinterest, bordering on pathological dissociation. The novella opens with him in the Parque de la Exposición, and his surroundings are recorded in leisurely yet relentless strings of noun clauses: children playing, couples chatting, pedestrians, flowers, carp in the pond, sakura branches in full bloom—all and more of which signifies nothing deeper to him in this moment: “Nothing foretold anything.” In the next instant, Nakamatsu turns inward, erasing the world, and “the pebbled paths disappeared, no serene gardens, or laughing families, or murmuring young couples, or ponds full of fish.” He even occasionally blacks out and finds himself in a new place.

Much of the novel’s content is taken up by Nakamatsu’s transportations: by foot, by minibus, and mentally into visions from the past. He cuts a solitary figure, dressed like a college professor, shuttling through the “dense streets” of the Breña district in the heart of Lima, amid “the vapors, the murmurs, the tobacco smoke and the alcohol, between hatred and rancor.” With his reticent “Asiatic temperament,” as the narrator puts it, he wanders in a “ghostly” fashion, meandering “through nooks and crannies, refuges, hideaways, surly and punctual, with his thick-lensed glasses, with no questions, no hint of quickness,” mixing with “lost addicts, the drunks, the schizophrenics, and the abandoned suicide seekers, prostitutes and queers drinking rat poison.” The encounters Nakamatsu makes on these urban excursions become stranger and stranger. He runs into Paco Mármol, a retiree and WWII buff, waiting for a taxi bus, “humming Tchaikovsky’s ‘Capriccio Italien.’” “How could one kill oneself quickly and painlessly?” Katzuo asks him. Paco Mármol immediately replies, “Gunshot to the temple.” Katzuo claps him on the back, and the two men laugh “uproariously, magnificently.” On the streets he is harassed by a bodiless voice that sounds like a “sob,” a “babbling,” “welling up from the ground and the roots of the trees, like groans rising in the distance.” It sounds as if it emanates from a “brood of flies.” In his own home, he begins to hear the keening and clamoring of tropical birds, “a concert of chirps and trills emerging bountiful from a recessed grove, with its greenery, flowers, shrubs, and open country.”

The monologues of the flies and the natural ambiances seem to reflect the collective past of the Japanese Peruvians, a historical context that weighs heavily on the events of Enlightenment. In the late-nineteenth century, traditional Japanese agricultural laborers, out of work under the rapidly industrialized Meiji government, began emigrating to countries in the western hemisphere, the first of which was Peru. A large number of these poor farmers came from the southern prefectures (both Higa Oshiro and his fictional hero Katzuo had parents from Okinawa). They wound up on the cotton and sugarcane plantations of the Peruvian coast, doing contract labor arranged by private firms as well as the Peruvian and Japanese governments. Many of those who couldn’t get work moved into the cities, and as a racial minority were restricted occupationally to shopkeeping and street peddling. The Japanese immigrants largely kept to themselves socially, more often than not marrying other Japanese (in the novel, Katzuo has recently lost his wife Keiko, and with her his remaining connection to the community). They bore the brunt of discriminatory laws and economic scapegoating that often oppress ethnic minorities, who are confined to either backbreaking labor or petty “middleman” merchant capitalism (Katzuo goes to his university where he teaches one day only to be abruptly and unceremoniously given an early retirement).

One of Nakamatsu’s means of coping with this history is to write about Etsuko Untén, a “haughty,” “arrogant,” and “brutal” friend of his father’s, while taking on the appearance and mannerisms of the great Peruvian poet Martín Adán. He becomes a severe stoic in the process, detached from the swarming world, “obliged to stay unchanged.” The only certainty for him is the “insuperable fact” of his own existence: “What he knew for certain was that he was living; everything else bordered on the metaphysical.” At other moments, his rejection of the world is expressed in cultural disdain. Katzuo is repelled by the traditional Andean clothes and customs of indigenous Peruvians, with their “colorful chullos” and “haughty faces outlined in the light.” He finds them “uncouth, brutish, crude” and “cartoonish.” In a dive bar he loudly whistles the Japanese national anthem “so that everyone would understand that Nihon was victorious, nobody could defeat us, even when we were living in an enemy country.” His path mirrors that of his historical hero Etsuko Untén—who became a brash supporter of Japanese imperialism during WWII—into lumpen squalor and chauvinism.

Nakamatsu and Untén not only share a similar danger of reactionary feelings and ideas, but also a premise: that “assimilation,” the overcoming of isolation and inequality, as opposed to nationalist separatism, is impossible for the Japanese in this place and time. On what basis could the end of this isolation take place? The values of freedom, equality, and dignity are scarce in Higa Oshiro’s fictive landscape; there are only the traumatic after effects of racism and coercion. It is worth pointing out in this context that Nakamatsu and the third person narrator never mention the election of the conservative Alberto Fujimori as president of Peru in 1990. His victory brought the Japanese-Peruvian community to the world’s attention (though it was won with minimal electoral support from the Nikkei themselves) but also began a new era of authoritative government and austerity policies for Peruvians. Shyue quotes Higa Oshiro saying in an interview that it took time before he figured out how to compose narratives about the Nikkei. “Only after forty years do they come out with ease. Because I finally managed to demarcate that world.” Perhaps that demarcation also applies to historical things that as of yet must go without utterance.

With his passivity resulting from the weighty history of deprivation and discrimination, what are the conditions for the possibility of Nakamatsu’s enlightenment (iluminación in Spanish, and kenshō or satori in Japanese Buddhism)? What will Nakamatsu’s wanderings, meditations, bitter outbursts, and betrayals of his suppressed sexuality amount to? I will only divulge that the closer the reader comes to the moment of “enlightenment,” the more she learns about the true circumstances of the text’s narration, and the more Higa Oshiro’s unique writing becomes bathed in irony.

Jennifer Shyue has furnished an English translation of The Enlightenment of Katzuo Nakamatsu that conveys the resonant darkness lurking behind the placid surface of Higa Oshiro’s writing. The experience is akin to wandering the dusty, hilly streets of Lima, making discoveries as exciting as they are tinged with melancholy, as if in some ephemeral way, “something definitive happened on just another nameless afternoon.”

Alex Lanz lives and writes in Brooklyn.

This post may contain affiliate links.