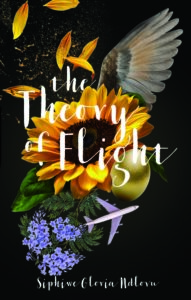

[Catalyst Press; 2021]

On the day of her death, September 3rd, when she finally lets go of the struggle of having to live with and fight HIV/AIDS for most of her life, Imogen “Genie” Zual Nyoni, the protagonist of Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu’s debut novel The Theory of Flight, ascends into the clouds above the Beauford Farm and Estate’s sunflower field on a pair of silver wings. By then the non-native flower field has been scattered with human bones from a massacre and gotten into the regenerative rhythm of dying and reseeding itself according to the seasons without living human intervention. Genie’s take off is a wondrous ending, watched by a group of survivors — a gang of street kids — and it is experienced by Genie herself as a sort of love that “releases a promise long held.” Most importantly though, her ending, which occurs at the beginning of the book, matches her body entering the world, which was “like all beginnings-beautiful and golden.”

What is a beautiful and golden beginning? A wet, crying, wrinkled baby? No. Genie starts out as a “shiny golden egg” that “traveled through her mother’s body and found its way onto her mattress” after Elizabeth Nyoni had spent the night with Golide Gumede, Genie’s father, who “shot down an airplane and in doing so created a race of angels.”

It sounds wondrous?

“However, most of you have eyes that are not for beauty to see, and because of this you will not believe that such a truly amazing phenomenon did take place. It’s because some of you will have doubt, and those of you who do not have doubt will be curious, that this story is choosing to be told.”

After I finished reading The Theory of Flight, I did not have doubt and I was definitely curious. I engaged the Internet in reading about the history of what is now Zimbabwe, formerly called Rhodesia, whose history seems to parallel that of Ndlovu’s fictional world in a number of ways. Not really knowing where else to start, I followed a mainstream Internet path on wikipedia, led by blue, clickable links, from the Shona language, to the Kingdom of Mapungubwe and its trades with people from Portugal in the 9th century, to the colonialist Cecil Rhodes and the British South Africa Company in the 1880’s, precious metals and mineral resources, cheap labor, the Shona’s revolts, European settlements, displacement of indigenous people, the rule of white minority settler government, the Land Apportionment Act which divided rural land along racial lines, guerillas, African opposition. I read about the Air Rhodesia Flight 825, which was a scheduled passenger flight that was shot down by the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) on 3 September 1978, during the Rhodesian Bush War and remembered that Genie’s father, Golide looked at the magnificence of the Victoria Falls on that very day, and that “ . . . as he waited for the airplane to fly overhead, he thought of how Frederick Douglas had, exactly 140 years earlier, escaped from slavery. He did not think this thought in order to justify his actions, he thought it because it was a thought one could think as one waited to shoot down an airplane.”

I read about revolutionaries and the country’s celebration of independence on April 18, 1980 and remembered that “a country’s independence is infectious and tends to permeate everything.” I listened to Bob Marley’s song “Zimbabwe,” which he performed at the government’s invitation during the festivities and I related that performance to the part of the novel when the character of Bhekithemba Nyathi, a journalist working for The Chronicle newspaper, had made his way to the stadium. When a man in dreadlocks got on stage and called out “Viva!” the “crowd went wild and Bhekithemba felt something stir within him — something nascent, a beautiful beginning. For the first time he became fully aware of the throng around him and of its elation and euphoria at finally being independent and free.”

I listened to Bob Marley’s song again and looked up the lyrics:

“Every man gotta

right to decide his own destiny,

And in this judgment there is no partiality.

So arm in arms, with arms, we’ll fight this little struggle,

‘Cause that’s the only way we can overcome our little trouble.”

Bhekithemba’s fictitious encounter with Bob Marley had “filled him with a pride in his country and in his blackness that he had never had before,” and when I then proceeded to read parts of Robert Mugabe’s actual victory speech on wikipedia, delivered at the same event, also attended by a member of the British monarchy, Charles, Prince of Wales, it dawned on me that it might have been Mugabe who had appeared as “The Man Himself” and “the current head of The Organization” in Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu’s novel, that often directly describes or openly hints towards historical events, people and places but rarely names them directly. The Man Himself. Who did the things he did, because he could. “It does not matter why. It never matters why. You do it because you can. I did it because I could. Power.”

In his speech on April 18, 1980 at the Rufaro stadium in Salisbury, Mugabe had said: “The wrongs of the past must now stand forgiven and forgotten. If ever we look to the past, let us do so for the lesson the past has taught us, namely that oppression and racism are inequalities that must never find scope in our political and social system. It could never be a correct justification that just because the whites oppressed us yesterday when they had power, the blacks must oppress them today because they have power. An evil remains an evil whether practiced by white against black or black against white.”

Now, 40 years later, with the ability to look back and connect the dots, The Theory of Flight contains and communicates the knowledge that the struggle and the trouble was neither little, as Bob Marley blasted into the crowds, nor that the wrongs of the past can be forgiven and forgotten because someone stands up and says that it must be done now, as Mugabe demanded in his speech.

The German language has compounded the word “Vergangenheitsbewältigung,” to give its speakers a sense of what it means to work through the horrendous parts of our collective past in order to be able to cope with it. Because we are of different generations, the word has different meanings to my stepdaughter and me. To me “Vergangenheitsbewältigung” is something that sooner or later enforces itself on every German. Ready or not, one has to deal with it. To my stepdaughter it is something that has been mostly done already, and maybe that’s because the word has always been so closely linked with the Holocaust, those specific events that lie for the next generation further back in the past.

In any case, “coping with the past — recent or further back,” is nothing one can do just now and be done with it once and for all. One has to learn how to do it, step by step, over a long period of time. The focus on learning is much in the spirit of George Santayana’s oft-quoted observation that “those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Reading about Mugabe’s records as Prime Minister of Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1987 and then as President from 1987 to 2017, many of his actions provide reasons for condemning. Is that a result of his 1980 resolution to forget the past? Is my present unfolding depending on how I currently treat the past? Or much more importantly: we. Nobody acts and is acted upon in isolation.

“Like any event, what happened to Genie did not happen in a vacuum: it was the result of a culmination of genealogies, histories, teleologies, epistemologies, and epidemiologies — of ways of living, remembering, seeing, knowing and dying.”

Genealogy

History

Teleology

Epistemology

Epidemiology

All of them interconnecting in their plural forms. Family lineages, the studies of the past, the explanation of phenomena in terms of the purpose they serve rather than of the cause by which they arise, the studies of the nature of knowledge, the rationalities of belief, methods used to find the causes of health outcomes and diseases in populations.

According to Wikipedia, by 2005 an estimated 80% of Zimbabwe’s population were unemployed, by 2008 only 20% of the children were schooling, the HIV/AIDS rate for individuals between 15 and 49 was 15.3% and in 2007 the World Health Organization declared the average live expectancy in Zimbabwe to be 34 for woman and 36 for men.

I did not learn these facts in The Theory of Flight but some of the implications and the consequences of these circumstances were related to me through the stories of Imogen “Genie” Zulu Nyoni, Markus Masuku, Valentine Tanaka, Emil Coetzee and about thirty more memorably fleshed out characters.

“For in telling stories we testify to the very diversity, ambiguity, and interconnectedness of experiences that abstract thought seeks to reduce, tease apart, regulate, and contain in the name of administrative order and control,” writes Michael Jackson in his book The Politics of Storytelling. I don’t know if one can exchange “facts” so casually with “abstract thoughts,” I don’t know if it makes sense to compare the existence of “the truth” that is attached to facts, with a “physical nonexistence” attached to the idea of abstract thoughts — but should I really care about these specific distinctions when I know that “while every human situation is subject to limiting conditions that lie largely beyond the reach of anyone’s will and understanding, no two individuals ever experience or react to these conditions in exactly the same way.” Is it only a question about fact and fiction how we communicate the truth about history? Or is it rather about time?

Genie, like her aunt Minenhle, had been broken physically in horrendous ways. Minenhle Tikiti’s interrogator “had butchered her face, burnt her body, crushed her spine” during a 1978 interview with The Organization, but that infamous C10 had not gotten to “that precious thing.”

Despite the cruelty, Genie’s aunt, her father’s sister, stayed unbroken. Same with Genie. As Valentine Tanaka, the officer who processes her for “The Organization” and who considers himself the best of the best, looks at Genie as she stands stripped naked behind the glass in the interrogation room, he realizes something that ultimately changes his heart. No interrogator, no matter how cruel, how thorough, smart or dedicated would be able to retrieve Genie’s most precious thing. That thing that broke Genie physically, “but left her intact.”

“You cannot break me. You see, I know for certain that my parents were capable of flight.”

Genie is “intact” because she is not corruptible. Those who carried out the massacre could break her body but not her integrity. There are areas in Genie’s being, parts of her body, that can’t be confused. Those areas are that of dense certainty. They are precious, not only to Genie, but to everyone who recognizes that preciousness in her.

The certainty of knowing that human beings are capable of overcoming — is that what flying is for Genie? Or is it flying as in fleeing, being able to escape? Flying as a reaction to somebody letting go of your hand when it was most needed? Flying as in reaching for the sky, as wish-fulfilment and maintaining dreams? Flying as in “going high, when they go low” as Michelle Obama keeps encouraging us who have to live with constant lies and tyrannical chaos and destruction? Flying as in “taking flight” like a young bird that begins a period of rapid activity, development or growth? Flying as a metaphor for freedom?

“You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time,” Angela Davis said in 2014 during a lecture at Southern Illinois University. When people in the novel talk about Golide Gumede, Genie’s father, they treat this sort of “acting” as something as essential for a country’s well being as having water run through pipes into a kitchen sink. “Now you see, a man like this is the kind of man that this country really needs. The man is building an airplane from scratch. Believes he can do it, too. He is innovative. Radical. Fearless.”

When we want to base our shared reality with each other on facts, we also must allow, acknowledge, and cherish the existence of magic. The Theory of Flight is full of magic, a magic willing to be observed by eyes that can see the beauty in knowledge, facts and far beyond. Genie is beautiful, because she possesses a knowledge that is not only attached to drag, lift, thrust, and weight, but also to truth, lies, failures, and hopes. No phenomena belongs only in one category, no person only in one body, and no country belongs only inside its borders.

“It’s about the history of your country, how it was never able to become a nation because the state focused belonging too singularly on the land. In colonial times belonging was attached to being a settler and in postcolonial times belonging is attached to being autochthonous. That means that throughout your country’s history there has always been some group or other that has not been allowed to share in a sense of belonging.”

Hence “the race of angels” and their love for elephants?

“And that’s when they appear with their formidable grace. Majestic. A herd of elephants, raising dust beautifully in the early morning savannah sunlight. The bull at the head of the herd raises his trunk and trumpets terrifically. All the elephants come to a gradual standstill on one side of the Victoria Falls. And then the elephant dives in close where the waters plunge over the edge. Every breath is held in unison. The ancient river and the mighty animal in perfect harmony . . .

A rite of passage made sacred by its sheer audacity. There is a wonder to it all . . . The possibility of the seemingly impossible . . . And there is this feeling that you get . . . a knowing . . . You become aware of your place in the world . . . You understand that in the grander scheme of things you are but a speck . . . a tiny speck . . . and that is enough . . . There is freedom . . . beauty even, in that kind of knowledge . . . It is the kind of knowledge that finally quiets you. It is the kind of knowledge that allows you to fly. You have to experience it for yourself.”

Franziska Lamprecht is an artist who started writing as an extension of the long-term process based works, she produces together with her husband Hajoe Moderegger under the name eteam. Their projects have been featured at PS1 NY, MUMOK Vienna, Centre Pompidou Paris, Transmediale Berlin, Taiwan International Documentary Festival, New York Video Festival, International Film Festival Rotterdam, the 11th Biennale of Moving Images in Geneva, among many others.

This post may contain affiliate links.