[Arsenal Pulp Press; 2020]

I opened Amber Dawn’s latest poetry collection, and there’s a content warning. Content warnings scare me because I don’t know my own pain tolerance, and I don’t know of a pain scale that truly grapples with how textual graphic description differs in affect from graphic images. I’m no master of how and when to give such warning for others let alone myself. The same week I sat down with Dawn’s book, I was listening to the TED Radio Hour on “Gender, Power and Fairness,” and the podcast host opened with a trigger warning. I was surprised because I felt the content indicated enough about the difficult material to follow. A trigger warning itself sometimes sets off alarm bells, so it doesn’t even help quiet the mind that hasn’t known what to do before with the fact that consent is so easily compromised. Twenty minutes or so into the podcast, I was triggered, and it wasn’t Tarana Burke’s story — it was what Burke said: “I feel numb.” My own body has felt numb for months now. The tingling sensation reminds me of my body’s freeze response to trauma. Tarana Burke, the founder of the Me Too Movement, even after all the response to #metoo, still feels numb. For writers with survivor stories, struggle is bound up in the work, even as Dawn’s content warning is blended into her author statement; Dawn writes, “Several of the poems explore how trauma — sexual violence, in particular — shapes story, both how stories are told and how stories are consumed by observers and audiences.” Why are survivors the ones writing about sex and decriminalizing sex work? I pick up difficult material because I’m searching, because I’m so convinced I must be missing something, because I still don’t seem to know how to hold the pain.

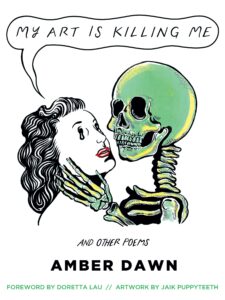

I haven’t read Dawn’s memoir or other works, so I won’t pretend to fully represent her experience of sex work or her story through childhood sexual abuse, dating violence and Title IX offenses, but I am inclined to read with a personal stake in the art of writing about traumatic memory and #metoo. Of course, I wasn’t eager to feel retriggered, but I couldn’t immediately close the book, and I also knew I couldn’t just go and get her other books. What drew me to Dawn’s new book was the title and the cover art by Jaik Puppyteeth, not the back-cover blips about the contents. I was captured by the rawly felt sense of tension: a caricature of a dolled-up woman at the mercy of an obnoxious green skeleton head. From the woman’s thought balloon, we gather the title of the poetry collection: “MY ART IS KILLING ME.” I don’t know what to do with that statement, but I understand the emotional necessity of the utterance. The statement is one that spoke to the desperation I too sometimes feel pushing and pulling me apart in my own creative work. Before I read any of the poems, I knew this would be a challenging read, not only stretching my mindset but also awakening my own body.

I decided to journal about the reading experience, so I could have a safe space for myself to pause and reflect freely. I didn’t want to spill on social media because that’s not always safe, especially when thoughts and feelings are in process. It felt affirming when I discovered Dawn comments on the lack of safety on social media platforms later in the book: “Does your public network see you and hate you in looping rounds? / Does logging on harm you? Does all this somehow feel familiar?” The next line is mind-breaking: “How do any of us go from touch / to touch screen?” It’s curious how she’s chosen to speak back through verse. There is even a collage poem in the book composed of tweets. The attention to concerns of the virtual and the digital is so exact and articulate: “all / miscarry on social media.” In our current world of social distancing, her attentiveness to social media struggles is so reassuring, yet the pointed censorship of the web is very disheartening. We are so disconnected from each other. Circles of mutual aid feel distant. What happened to holding and carrying safer spaces? I often feel that there is information missing to connect two thoughts or texts in my head, much is unspeakable, therapy is not always desirable or accessible, and art is the only way to define an answer, even a non-answer or a slant gesture or shade I can pause and unwind and rewind.

As I made a point to write, I kept putting the book down in the middle of poems, pausing, sometimes to write about something that struck me, sometimes because I did feel triggered. However, I never felt lost when I picked the book up again. Even when I returned to the book in the middle of a long poem, I remembered where I was and what was happening, maybe even why I’d stopped my train of thoughts there and stepped away. It’s a very memorable book and one of a kind in its bold stands. There’s a lot I don’t understand and a lot that resonates. I still have pictures from the earlier pages of the book stuck in my head, especially the poem “Hollywood Ending” calling out actresses who perform sex workers but do not support sex workers. My writing was not so much to remember the contents of the book but to be mindful of my own mental, emotional and bodily response.

Just reading the foreword and the first poems, I started to ask a key question: what is the role of sex workers in the conversation surrounding sexual violence and Title IX, and why have they been left out of the conversation for so long? The answer is obvious from her book: erasure, stigma, discrimination, abuse, injustice. Dawn argues that sex workers are so focused on consent, offering an intimate picture of human longing; meanwhile, sex workers are conflated with trafficked sex slaves. The first long poem “The Stopped Clock” in the collection sets up the primary narrative arc of the book surrounding her stories from sex work to academia and the writing life. In further pieces, she speaks of the sexual offenses by faculty against herself and other students. She suggests “the tenured professor” is a composite character, carrying the heralding line “everywhere there is a man.” I am struck by the intimidation of the speaker from the very same faculty: “He asked Are you afraid / that after you write down everything that happened / you will no longer be lovable?” The words are absolutely gut-wrenching. The thought that a memoir could make or destroy an academic writing career is so crippling too.

A survivor tells their story, whether through a creative practice or in legal proceedings, and then what happens? Survivors are not compensated for their labor, and that is also unjust. Dawn shares tales of both instances. She has testified to a reporter and presented as an author. Both times she was barely reimbursed for transit costs. Why is art not properly compensated? It seems even more horrifying from the perspective of a sex worker and a survivor of sexual violence because I imagine you’ve examined your worth but you may feel burdened to give of your art in the pages of a book. In the foreword, Doretta Lau writes, “I begin to wonder why we expect artists to do our emotional labor for us.” So often, the pressure to educate is laid on artists and writers. Writing the story is not just a risk; it’s also a constant struggle against the devaluing of the art in the first place. For little or no pay, no one should have to brace themselves when they divulge truths about self and face stigma. Lau continues in alignment with Dawn to urge active, affirmative consent not only in sex but also in self-disclosure: “I want us to live in tenderness that is a choice, a display of vulnerability. I do not want us to be tender because we’ve had bruises inflicted upon us by the people around us.” Publishing a survivor story should be an affirmative decision, not coerced and certainly not provoked by false guilt.

Actually, there may be something spiritual about writing the body through trauma and healing, almost sacramentally sacrificial; Dawn writes, “I am here for the divine and complex work that is healing.” The book itself begs sex workers, survivors, artists, writers and readers to approach one constant question: “Who is being consumed?” In return, as deliberately, the voice of the work claims and reclaims: “This is my body.” Reading a formative account of a religious ceremony adjacent to tragic events of sexual violence, I was in awe thinking of the body’s sanctity anew, thinking too about the mantras the writer explores through poetry to refocus the mind and stop the thoughts. Read, “Don’t think about violence,” over and over. Much of the power of the work, which may trigger, is its work in metaphors: “If you think about an apple, reset the timer / as many times as it takes.” Dawn explains, “The mind processes trauma through metaphor.” Unfortunately, the mind reprocesses trauma through metaphor too. A survivor may not know another survivor’s story, yet violations suffered by others, especially veiled in caricature and metaphor, all feel like trauma. Something I particularly appreciate about her perspective is how through it all she sees and knows and claims the reality of dating violence too.

I was struck by the accounts she offers as well of other survivors attaching to not only her story but also her very body. I was overwhelmed with so many emotions, reading the collage poem of tweets in response to her memoir, tweets like “we haven’t met but. . .” or “his hands on me [space] his fist [space] your poetry.” Dawn writes, “I know exactly where these disclosures would soft land on my body.” She even describes in other sections of the book individuals running up and embracing her at readings. How does any writer make sense of how readers respond to such work? What compels them to jump outside their shaking bodies and physically cling to her? And how does it feel to know that kind of embrace? Maybe it feels soothing to share someone else’s burden for a moment; maybe the weight is too much. It seems that an artist knows and a sex worker knows. My Art is Killing Me reflects what it’s like to intimately carry someone else’s exhale; Dawn’s work becomes like a release of the tension, a liturgy on the job. Sex work is work, and writing is work; both are an art, and both may be an art of healing.

What liberty does her art offer the world? Dawn herself wrestles a lot with genre in the book, as she asks hard questions about genre categories and explores experimental forms, often taking a long hybrid form in this collection. Her shift from project to project, writing the MFA thesis and landing her debut book, is writ large to the narrative. If her work is testimony to writers also on a journey, she knows too well the cautionary tales so many of us are told. She herself received the same advice: “more than one professor warned me / not to confuse creative writing with therapy.” Then she continues with her own honest struggle with memoir and closure: “I mean, what survivor can hold up their unbroken [space] reality / in the academy? Fantasy is strategy. Tunnel light. It’s the genre / that would allow me to pen The End.”

My Art is Killing Me itself closes with such an incomprehensible line: “And will poetry still help me make this claim?” How does anyone answer that question: I dare not. It’s not even really a question posed for a response. So often we are compelled to respond when sometimes listening means simply affirming the struggle. Not every vulnerability offers a safe and open forum for response, especially when an offender is lurking around every corner. Sometimes maybe actually the body needs a shield. No one can lift the burden. That’s very much what the book is about. If the book is sold to and for a collective, this is a personal project, a project of struggle. Popularizing the caricature of the sex offender with Jaik Puppyteeth’s comic art may ease the tension. When drawn as a skeleton grinning in a black hood like a devil, the offender’s answer is a mockery of himself: “Being hated is just part of the job.” The voice is resistant and bold. Still, I don’t know. The death of the ivory tower and the monopoly of social media: will it come finally? Not the death of poetry and love in its place. My Art is Killing Me is a cry. A plea.

Kara Laurene Pernicano earned a MA in Literary and Cultural Studies with a Certificate in Women’s, Gender & Sexuality Studies from the University of Cincinnati. Currently, she is a MFA Candidate in Creative Writing and Literary Translation at Queens College, CUNY and an Adjunct Lecturer in English for CUNY. Artist and writer, she celebrates intersectional feminism, queer love, art and healing. Her creative work explores hybrid image-text practices.

This post may contain affiliate links.