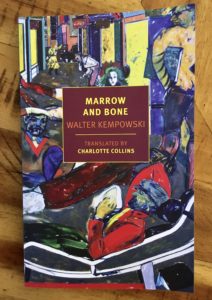

[New York Review Books; 2020]

Marrow and Bone takes place in the late 1980s in a Germany that has, in rapid succession, lost two World Wars, perpetrated one of the largest and most horrifying state-sponsored campaigns of violence, genocide and terror in world history, and over a slightly extended cool-down period, begun to forget about the last of these things. It meanders across a spectrum of post-war German landscapes, from the prosperous West German (at the time still a separate nation from the Communist East Germany) city of Hamburg to the formerly German territory of East Prussia.

East Prussia is now a part of Poland. Looking at a map today, it is difficult to believe that it was once a part of Germany — it lies not just east of Germany, but in the relative center of neighboring Poland. In this way, its presence is somewhat ghost-like, a memory of a reality that was, even when it was true, only ever political. Yet, after the end of World War II, the German population of the region was, along with other German populations throughout Central and Eastern Europe, expelled from the countries in which they lived and sent to Germany. Walter Kempowski wrote Marrow and Bone in 1992, at a time when this history had already, like sediment at the bottom of a glass, settled.

Marrow and Bone is ostensibly something of a road trip story. Jonathan Fabrizius, the story’s protagonist, is a resident of Hamburg, a city in West Germany at the (unbeknownst to him) twilight of the Warsaw Pact. In the aftermath of the World Wars, West Germany has become an economic powerhouse, and an exemplar of the kind of capitalism that the United States encouraged its allies to practice. Jonathan is a somewhat idle sort of person — his uncle owns a factory and sends him an allowance, which he supplements with periodic and desultory freelance writing assignments. He fills his time, largely, by going to shops and restaurants, considering whether or not to buy certain things, and getting in arguments with customer service personnel of restaurants and galleries. He operates, in short, as a normal West German citizen, something not so different from a normal citizen of the United States. In the course of this existence, Jonathan is offered a chance to participate in a press junket sponsored by a Japanese manufacturer of sports cars throughout the East Prussian countryside.

In addition to this identity as a West German, however, Jonathan is an expellee from East Prussia. He does not remember the event in any great detail, only flashes, which he bemusedly considers in the early sections of the book, little knickknacks of thought that do not appear to have any relevance to his current life: the church steps on which his mother’s body rested after her death, the beach on which he was taken aboard a boat to Germany, the flat and grassy clearing where his father died at the hands of the approaching Allies. When he first thinks of this incident, it is in the same moment as he thinks about a particularly popular new type of bed, the success of which has allowed his uncle to send him an envelope of money, which the uncle specifies is for a treat. At the time, he is not bothered by the proximity of these thoughts to one another.

The overall mood of the novel combines these two elements, of trauma and consumption, the trauma kept at arm’s length while the consumption is real, material, and close. While perusing paintings at a gallery, Jonathan is tickled by a series of paintings of “. . . cowboys drinking arsenic from bottles and exploding down below; cows, their front halves bloated into elephantine monsters, hindquarters dissolving into puddles of green slime.” He buys one. In a Turkish restaurant he and his girlfriend (a researcher who studies cruelty as an artistic concept) dine on kebabs of “the roasted flesh of rams that had been tortured to death.” While studying a photo of the Turkish countryside in the restaurant, Jonathan notes that the landscapes include no portrayal of “. . .the Armenians who were driven into the desert to die of thirst along with their wives and children.” This somber observation does not stop him from getting into an argument with the waiter.

Soon thereafter, Jonathan meets his co-travelers for his trip across East Prussia, a scene of barely-recalled trauma for him. The three (a racecar driver, a representative of the company, and Jonathan) embark on the trip with a mechanical crew in pursuit. The undertone of queasy brutal material consumption gradually sours in the Polish countryside. There is little to consume, to the ungracious disappointment of the trio — they find the cuisine lacking, are unable to find the souvenirs they planned on getting (shortages), and their accommodations are not to their liking. They cadge various bits of food and drink where they can, and awkwardly make their way through the countryside.

At this point, history begins to re-intrude. East Prussia, the trio find, is haunted by past occurrences. The names of cities have changed, but the residents remember both the lost names of the cities and the actions of the Germans that once occupied them. A refrain throughout the book, whether from fellow tourists or occurring to Jonathan in the description of his writing assignment, is “not too much history” — each extra unit of history displaces another of enjoyment or, in the case of the trio, provokes bemused resentment at the material shortcomings of their socialist hosts.

Finally, however, as Jonathan and his companions journey deeper into the countryside, this aversion to history proves unsustainable. Jonathan, without intending to, finds himself at the site of his own historical trauma — the church steps on which his mother died, the field of combat where his father was killed. Confronted by this undeniable and physical (and inescapably present) manifestation of his own past, he is overcome by despair at the depth and breadth of the history that has passed, both through him and through others. In an utterance which is uncharacteristically free of sarcasm, he ends this encounter by wandering away from the town, possessed by mournful thoughts about the past:

It’s all for nothing, he thought, again and again. And: who’s to blame?

This question is not answered, either in the novel or in the vast majority of the real-life historical traumas that are arrayed, overlaying every physical landscape, all across the world. And indeed, the question of blame is one that is easily avoided, which is one of the most prescient observations of the novel. Today, in fact, the leader of Germany’s resurgent fascist party, Alternative fur Deutschland, is a vertreibene, a descendent of East Prussian expellees, and the very memory of that event has become a right-wing touchpoint. A poll of West Germans in the decade following the end of World War II indicated that only 5 percent of them felt “guilty” towards Jewish people; less than a third thought that Jewish people deserved some sort of reparation. This is not to say that they thought no one had been hurt; there was a strong current of political thought that the Germans, themselves, had been most victimized in the war. Without allocating or assuming blame, the powerful retain or rediscover, over time, their ability to formulate grievances against the powerless; those grievances occlude the original violence, but the residue remains.

How does one confront the fact of one’s power over someone that one has wronged? In Marrow and Bone, it is an embarrassing shuffling around: the Germans are, by turns, generous and wronged, aggrieved and apologetic, amused and enraged by the Polish residents of the formerly German East Prussia. They are aware of the economic power they exert, but unable to precisely pin down the reason behind their feeling of awkwardness and spoutings of guilt.

The assumption of guilt is a personal choice. It cannot be allocated by the simple fact of defeat, or by the sight of disparities, or the thought that someone expects it of you. It has an intrinsically and inescapably empathetic origin — one has to understand the suffering of another, and to simultaneously understand that one is responsible for that suffering. The assumption of guilt rearranges one’s sense of the correct material ordering of the parties involved. To assume guilt is to accede that one should be deprived in order to ameliorate the deprivation that one has created for another.

It is difficult to say what can rearrange priorities in this way. In Marrow and Bone, Jonathan stands on the ground on which his mother and father died, and their sufferings, as well as the sufferings of the others around him and preceding him, become too real for him to ignore them. The awareness that this describes is emotional as well as intellectual. For Jonathan, it’s the realization of something that, though he had been thinking and talking about it for years, he had never really known in the way that he knew about his own possessions, the quality of his food, the condition of his own apartment. History has a way of staying separate from life. But, this separation is a barrier between where societies are and where they need to be. Despite this dire need, as for the characters in this novel, it is unclear how that awareness will occur, or if it ever will.

Eamonn Gallagher is a writer living in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

This post may contain affiliate links.