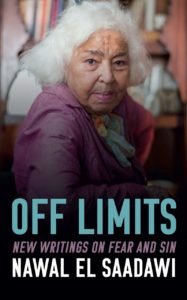

[University of Chicago Press; 2020]

Tr. from the Arabic by Nariman Youssef

Nawal El Saadawi’s name is, for many, regarded as synonymous with Egyptian feminist thought and activism in the last half-century, but she may be unfamiliar to English-language readers. At age 89, El Saadawi is seven decades into a writing career that has crossed genres as well as continents. She began her career as a physician in the Egyptian countryside but turned to writing and politics upon realizing that her patients needed something more like political healing. A burgeoning understanding of the hegemonic power of patriarchal ideologies catalyzed her turn toward feminist thought. As she wrote, “I discovered the relation between love and politics. Between poverty and politics. Between sex and politics.”

She discovered these relationships at great personal cost. While continuing to work in healthcare, El Saadawi became persona non grata with the publication of her book Woman and Sex, which was condemned by the Egyptian regime and led to her ouster from a position at the Ministry of Health. She was imprisoned for three months at the end of the Sadat regime, and persecution for her feminist thought led to self-exile in the early 1990s. Roundly celebrated in Europe and the United States with awards and honorary doctorates during the 80s and 90s, El Saadawi’s relevance for US readers has not waned since her permanent return to Egypt in 1996, and not only because ever more knotted geopolitical threads tie the two regions together. At a moment when contemporary American politics and politicians are inseparable from (nay, synonymous with) gender-based violence and discrimination, El Saadawi’s newest writing on oppression in the context of a religiously-affiliated autocratic government may feel familiar and can be profoundly instructive for contemporary struggles.

The thirty-one short essays in Off Limits touch on a range of topics including memoir, politics, history, and feminism, followed by a longer piece on the topic of “philosophy and change.” In each, it is El Saadawi’s playful shuttling between genres that sheds light on what she regards as the ongoing work of politically engaged feminism in the Middle East. The pieces are not full-length essays, though they do follow unpredictable lines of thought as El Saadawi remembers and addresses friends and rivals, both those who lived the praiseworthy, unconventional lives of prisoners and exiles and those who stooped to the depths of cowardice and complicity to preserve their wealth and the country’s status quo. The prose is by turns scornful and gracious as El Saadawi considers how members of her own family enforced patriarchal restrictions while others sowed the seeds of a life devoted to resisting them. Above all, these pieces demonstrate the potential for curiosity about the world to fuel political activity: El Saadawi works to understand, for instance, the “tension between crude tyranny and defenseless insecurity” that underlies “pure power,” and then considers how advocacy might dissolve it.

Off Limits was carefully and movingly rendered into English by Nariman Youssef, who, in addition to translating The American Granddaughter by Imman Kachachi, has published Summer of Unrest, an account of her experience in Tahrir square in the 2011 uprising. The London-based Gingko Library, which features MENA work in English translation, is the publisher of Off Limits, and is notable for occupying a unique space in the publishing landscape. In addition to its publishing arm, Gingko is committed to programming and conferences that promote cross-cultural understanding. Last year, Gingko organized a number of events surrounding the publication of A New Divan: A Lyrical Dialogue between East and West, which features twelve Arab poets in dialogue with twelve poets from the West in commemoration of the 200th anniversary of Goethe’s 1819 West-Eastern Divan. (Marjorie Perloff selected an accompanying new translation of Goethe’s original text as one of the TLS books of the year for 2019.) In 2020, it’s more important than ever to recognize that small (and smallish) presses can, in the financially risky and editorially backbreaking work of commemoration and translation, drive the conversation around literary history in the political present. On this note, Off Limits itself calls readers deeper into a historical, literary, and political situation that only the American exceptionalism lingering in our personal canons has permitted us to ignore.

There are aspects of El Saadawi’s writing that may be difficult to access for (though not entirely off limits to) English-language readers who lack a precise understanding of the situations, personal as well as geopolitical, that prompted these pieces. For these readers, this reviewer included, the volume would have benefitted from an extended introduction and additional notes on the original publication of each essay. In another sense, each essay floats provocatively against the backdrop of El Saadawi’s own wanderings across three continents and their respective cosmopolitan cultures. She closes an essay about a stint in Europe by considering the strangeness of such a life: “I lay on the beach under a warm, gentle sun and let my imagination stretch itself from Sharm el-Sheikh on the Red Sea to the coast of Catalonia on the Mediterranean, from a place that would erase my existence to a place that honors me and celebrates my words.” El Saadawi has written more traditional autobiographies (such as A Daughter of Isis, translated in 1999), but these essays continue to insist that feminist work is informed by female life, and by the strange brew of personal and professional freedoms and restrictions imposed upon politically engaged women writers today. Despite their different circumstances in the U.S. political environment, feminist writers like Claudia Rankine, Maggie Nelson, and Masha Gessen insist on this point in their work.

Reading Off Limits in English raises a serious question: now that they have been translated, to whom are these essays addressed? The fact that this question is not immediately answerable may itself be one of the work’s major contributions. Perhaps we Western readers do best to overhear a conversation that was not intended for us. That is, the English translation of Off Limits gives new readers access to one significant pathway by which feminist and anti-imperialist principles have been presented by Arab writers to Arab readers in the Arabic language. At times, El Saadawi’s focus is on equality under the law. Several essays demand reform in family law, calling attention to the fact that in Egypt, husbands can still put their wives and children on the street by speaking the word, taleq (you are divorced). At other times, El Saadawi turns to the broader effects of misogyny and patriarchy that linger in the wake of legislative change. “Today,” she writes, “we have women whose minds are veiled even if their hair, arms, legs and knees are exposed.” The first sort of writing is informative for Western readers, but the second may be more compelling because it shows how similar feminist struggles in the United States and the Arab world can be. El Saadawi calls on the work of the American scholar Daniel Cutrara as she urges religious audiences to recognize the power of what may seem like sacrilegious work. When she claims that “innovative cinema has the power to modernize religious thought,” she is speaking about the Egyptian film Closed Doors. But she could make the same argument to an evangelical women’s group in Atlanta about The Good Place.

El Saadawi is adamant that feminist work, a key component of which is feminist writing, must continue in the face of its adversaries and of complacency that arises in the wake of longed-for progress. To this end, global elites and NGOs come under especially harsh scrutiny in many essays for their blindness, self-serving practices, and hypocrisy; it’s the worst kind of betrayal to proclaim a desire for peace and justice and implement only the most lukewarm of procedures to ensure it. More broadly, El Saadawi reserves special scorn for any and all unilateral decisions, not only those made by men on behalf of, or without the consent of, their wives or daughters, but also those made by colonizing countries and their bureaucratic apparatuses without the consent of the people they brutalize in the process. In every one of the essays in Off Limits, El Saadawi calls for an ethic characterized by relating across difference that, far from reproducing discriminatory violence, might attend to difference as a catalyst of freedom. This is how, in the book’s closing notes on philosophy and change, El Saadawi can juxtapose John Locke and the Egyptian writer Taha Hussein as she upholds the intellectual’s duty to oppose political injustice. This is not a naïve universalism but an invitation. In these essays, Nawal El Saadawi insists that encounters with voices like hers have been deferred for far too long.

John Steen is the author of Affect, Psychoanalysis, and American Poetry: This Feeling of Exultation (Bloomsbury). He holds a PhD in Comparative Literature from Emory, a Master’s in Social Work from Columbia School of Social Work, and a job as a psychotherapist in New York City.

This post may contain affiliate links.