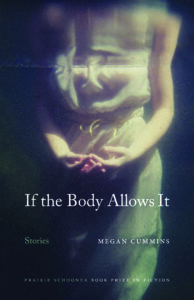

Megan Cummins writes deeply human stories about deeply human qualities: grief, illness, foolish self-reliance, untenable togetherness, and that, yes, we do tell ourselves stories in order to live. The stories in her debut collection, If the Body Allows It—winner of the Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Fiction—train a masterful eye on our chronic conditions, from illness to debt, in order to explore the question of what our surroundings, our relationships, our minds, and our bodies allow. The book’s launch will be hosted on September 9th, digitally, at Community Bookstore.

Megan Cummins writes deeply human stories about deeply human qualities: grief, illness, foolish self-reliance, untenable togetherness, and that, yes, we do tell ourselves stories in order to live. The stories in her debut collection, If the Body Allows It—winner of the Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Fiction—train a masterful eye on our chronic conditions, from illness to debt, in order to explore the question of what our surroundings, our relationships, our minds, and our bodies allow. The book’s launch will be hosted on September 9th, digitally, at Community Bookstore.

Kyle Williams: I’d like to start by talking about place, because I know it’s something we both think is important. The settings in this book feel very real and lived-in, and evocative of actual places. I remember emailing you a few years ago to rave about how much I loved “We Are Holding Our Own,” specifically that setting of the small town off Lake Huron, and you wrote back that there is something about towns near large bodies of water. So what is it about towns near large bodies of water? What does that region near the Great Lakes do for you and your fiction?

Megan Cummins: There’s a stark divide off the lakes in Michigan between the people who live there year-round and the people who go there to summer, and how—and I think this is true of most places on water—most of that waterfront property is owned by the people who do not actually live there. That’s something I’ve always been aware of; I admit to being a summer person on Lake Huron—growing up, we would go to my grandfather’s cottage on the lake. That place has always captivated me, because I love it, but also because of that tension. The place itself is conflict.

The Midwest, generally, is fascinating to me as a place of conflict, where states like Michigan or Wisconsin can flip for elections, because it feels like the assumed identity of those places is ever-changing. I suppose I could make an analogy here to waves on water, but.

A simpler answer could also be that it’s where I grew up, where I called home for twenty-two years. All the stories with teenage characters in the book are set in Michigan, and that teenage experience is linked inextricably to Michigan.

But “We Are Holding Our Own” does take place from the point of view of adults, and is focused on a very adult conflict.

That is the second-oldest story in the book. The first draft of it was written, I think, in 2010. I was still figuring out who I wanted to be as a writer, and what I wanted to write about. At that time I hadn’t really accepted my love of writing about teenagers, and thought there was something un-literary about it. As a very impressionable twenty-two-year-old, I wanted to be seen as a sophisticated, literary writer. Of course, I’ve since realized that’s silly.

I’m really interested in this idea of place as conflict. There is, of course, a long history of regionalism in American writing, but it doesn’t really feel like something that’s currently in vogue. Regionalism isn’t taught, for instance. So, in shifting from the Midwest to Newark, where the book’s frame takes place, could you talk a little bit about that idea of place as conflict, especially when it comes to a real named place?

As an aside, it’s interesting to think about how, why, and when writers name a real place rather than make up a place. I think you’re right that regionalism isn’t taught. It almost feels like maybe there’s an attitude that it can’t be taught, and that there’s an assumption that the settings we write about come out organically, without thought. Which is obviously not true.

I chose to set the frame in Newark for a couple of reasons. It was a place that I lived in for several years, during and after my MFA at Rutgers–Newark. I really did fall in love with the city, but I knew that my experience of the city was limited. I was only there a limited time, as an adult, and I lived and worked on or near campus. And when I imagined this character, Marie, who is at a point in her life where she’s not really doing anything right, one thing I imagined as stable for her is her love for where she lives. But her experience of that love, of Newark, is quite small. She often doesn’t even really leave her block, and when she does she takes a train to work at a law firm in the city. She’ll go to yoga classes, she’ll go to the movies, she’ll go to theater in the Park—she’ll go to a lot of things that are results of gentrification. I hoped to create this tension between her love for a place where she is still an outsider, as she feels herself to be an outsider everywhere in her life.

Bringing up gentrification is an interesting point, about “background” conflicts in these stories not being background at all. When you’re writing about a real place, do you feel you have a responsibility to get that place right, or to do right by the people who really live there?

Yes, I do. And that question speaks to the fact that it’s impossible to write a book that’s not political, whether or not you make a conscious choices toward the political. It was important to me, writing about Newark, to strike a balance between portraying a real place, but through the protagonist’s limitations. Because Marie does have quite a few limitations: her world is so small, and her circle is so small. I do hope I did right by Newark, even through the eyes of this white woman who’s enamored with the city, involved in it, but not by any means a political activist. Probably the most overtly political thing this book addresses is access to healthcare, but even there it only addresses the parts that are most relevant to her. It’s difficult, through the lens of a singular person, to address every issue, but I was hoping to present some ideas about healthcare and the gentrification of American cities.

There’s an interesting connection, when thinking about Newark, gentrification, and literature, in that the mayor of Newark, Ras Baraka, is the son of the poet Amiri Baraka. I would have to look up the specifics, but I do remember a conversation when he was elected of the importance of not making Newark the next Brooklyn. It’s something the city is very aware of, and so a necessary part of these stories.

A formulation of this that has stuck with me is Colm Tóibín’s. He told this story in his class at A Public Space about teaching a workshop and telling this workshop that he wanted to write this story about a love affair which would likely be uncomfortable for the real couple, and this workshop had apparently told him he had no right to write that story. His quip was, “I am a writer: I have only rights, and no responsibilities.” Which is just a lovely witticism, and one of those things that is probably damningly false and necessarily true at the same time.

It’s a process. Probably, I draft the rights and edit the responsibilities. I draft relatively quickly, and write things that come immediately—which, for me, is usually interiority and image. After that, I add in the layers like place, politics—which are there, of course, I know I’ll flesh that out when I edit. But, most immediately, what comes to me is the character, their thoughts, and the close, physical spaces they’re in.

I do want to ask you about the interiority in these stories. You do a beautiful job of mapping interior states, and taking interiority on its own terms. Most interestingly, to me, is that the interiority in this book is treated like action, scene, or conflict itself. In “Countergirls,” one character’s inner monologue says, “but thinking so was unkind.” Which is different than an unkind thought—it’s the actual thinking that is unkind, in that formulation. How are you thinking about weighing interiority with scene? And do you see interiority as having the same forward momentum as scenes and dialog?

Yes, absolutely. I’m trying to think of writers I love who have used interiority really well. Laura Kasischke is a big influence on my writing; her poetry has been impactful regarding what I admire in imagery, and her fiction is extremely well plotted but also driven by interiority. There is also Alice Elliott Dark, whose story “In the Gloaming” is a beautifully thought-driven story.

Interiority, accessing that inner life of a character, is really the main reason I’m interesting in writing at all. A plot isn’t interesting to me unless I know what the character is feeling about what’s happening. I view the thoughts of a character as a complicating force in a story.

“Countergirls” is a good example. The story is about a complicated family situation—a daughter comes to dinner, revealing that she is pregnant—but it wouldn’t be a story without the mother’s thoughts, which form this tangled web that reflects who she is, how she thinks of her daughters, and how she thinks her own life has turned out. Without that it would be, what, a family has dinner then goes out on a boat ride?

I love thought as a complicating force, and it reminds me again about this collection’s relationship to conflict. A central component of all these stories is the chronic condition, whether that condition be a chronic illness—you mentioned healthcare a moment ago—or things like class, debt, addiction, grief. What is chronic is really a focus for these stories, which is incredible because, generally speaking, narrative is bad at chronic conditions. Stories often demand a much more immediate scale. How were you thinking about bringing chronic conditions into these stories?

Chronic conditions drive each story, as well as the entire book, on a more meta level. Each story in the book is built around a chronic condition. The chronic condition is in the passenger’s seat of each character’s life—not driving the car, but the backseat driver, right, the voice they can’t get out of their heads, influencing their decisions with or without them realizing it.

It was important to me for the book to explore how these things we think of as “background” are actually the things that might identify us the most. When I was first diagnosed with lupus, I happened to meet up with a former mentor of mind from my undergrad. He was a deacon in the Catholic Church and he said to me, “This will make you who you are.” I was twenty-four at the time and I thought, “Well, no, it won’t.” But it did. Of course there are other things that made me who I am as well, and no one wants to be defined by those background things we all try to escape. But the chronic conditions of our lives do play a part in the people we become, and the decisions we make. So each story has a chronic condition in it, you could say I chronically explored the same themes. Some readers have found and will fine that repetitive—the book was rejected from a lot of presses saying it was “redundant”, but that repetition does mirror the relentlessness of a chronic condition.

I wrote an essay for Guernica sort of about this. The idea of that essay was how guilt attacks in a way similar to an autoimmune disease, where the body attacks or rejects itself. Guilt does look like a psychological manifestation of a kind of autoimmune response. In same ways this book, and the character of Marie, grew out of that idea. And, as a writer with a chronic illness, I was interested in fictionalizing that experience of what the body does and does not allow you.

It’s not something we hear enough about, that practical, tactile aspect of a chronic illness, especially in the life of an artist.

Like, my whole life since my diagnosis has been built around having health insurance. And so of course that has affected my life as a writer. It’s meant, for instance, that I couldn’t not have a full time job that gave benefits; I’ve had to jump into work environments that were not jobs I was passionate about or might help my future career in writing or publishing. Even more than I ever wanted to write a book, I wanted to have health insurance.

At her book launch for An American Marriage, Tayari Jones spoke to that myth that a writer has to completely devote their lives to their art or they’re not really a writer. She said, “Busy people have stories to tell. They’re busy!”

We’ve brought up the frame a little bit, and I would like to talk about it. The frame of the book is that all the stories have been written by Marie, which we see through the five stories that head each part, and the concluding story. That frame adds a whole meta layer to the book and to each story, and complicates the idea of the author in a way I find really fascinating. Who do you think these stories belong to: you, or Marie?

This book didn’t really become a book until I gave those stories to Marie. I am curious what a reader who doesn’t read the blurb on the back will think of that question, though, of whose stories these really are. I don’t know that I can really, truly answer that. But I am interested in those layers of removal: what I can learn about myself by giving some of myself to a character, what I can learn about writing by giving my stories to a fictional writer. That layer of removal really opened the book for me, and I felt like I could get away with more, that I had more freedom to be a little bit weird, maybe a little bit more obsessive.

It creates, I think, a compelling case for writing as being its own story.

Writing is self-exploration.

To end on a bright note: I love “Higher Power” as a story that, on the meta-level, is about its writer processing her grief. Do you believe in writing as a mourning process?

I believe in writing as a processing process. It was really intentional, putting that story at the end. So many of the stories take place from points of view that are not the one in “Higher Power,” the point of view which Marie doesn’t really allow herself until the end. We get stories about addiction from the point of view of a daughter looking on her father, from a friend looking on a father. In that story, we finally get the father. In some ways it’s a wish-fulfilling story, where Marie is trying to imagine what life might have been like had her father lived, had her father gotten sober. But even in a story, we can’t imagine a life that’s free of pain. It would be untrue.

If the Body Allows It

If the Body Allows It

Megan Cummins

University of Nebraska Press

September 2020

Megan Cummins is the author of the story collection If the Body Allows It (University of Nebraska). She is the managing editor of A Public Space and A Public Space Books and lives in Brooklyn, New York. She is on Twitter @cummins_megan.

Kyle Williams is a writer living in Brooklyn. He is an MFA Candidate at UT Austin’s Michener Center, Interviews Editor for Full Stop, Director of Communications for Chicago Review of Books, and A Public Space’s 2019 Emerging Writer Fellow. He is on Twitter @kylecangogh.

This post may contain affiliate links.