This essay was first made available last month, exclusively for our Patreon supporters. If you want to support Full Stop’s original literary criticism, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter.

This “mysterious power that all may feel and no philosophy can explain,” is, in sum, the earth-force, the same duende that fired the heart of Nietzsche, who sought it in its external forms on the Rialto Bridge, or in the music of Bizet, without ever finding it, or understanding that the duende he pursued had rebounded from the mystery-minded Greeks to the Dancers of Cádiz or the gored, Dionysian cry of Silverio’s siguiriya.

—Federico García Lorca

All love songs must contain duende. For the love song is never truly happy.

—Nick Cave

Perhaps some remember the first time they were exposed to images of violence and death. For me, it’s hazy. It might have been the art house movies, some R-rated, that my parents brought me to back in the 1970s. I remember Australian New Wave films like Picnic at Hanging Rock and The Last Wave. And The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, about an Aboriginal man wronged by society who goes on a murderous rampage, killing white folks. That night I tossed and turned in bed, soaked in sweat. I had a similar response to Easy Rider. The last scene when Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda are shotgunned on their motorcycles. My father resembled those marvelous hippies, and also rode a motorcycle.

Or was it, perhaps, when my mother read me Roald Dahl’s short stories? In the middle of “The Swan,” from The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Six More, she paused at the point where a boy with a rifle is savagely bullying another boy. The bully ties the boy to railway tracks, almost killing him. Later the bully shoots a swan, cuts off its wings, ties them to the boy. Did my mother, while pausing, ask herself if the terrifying narrative—classified as children’s literature—was appropriate for me? That swan, both dead and alive, is still lodged in my mind.

I’m grateful that my parents allowed me to absorb such a diversity of potent art when I was impressionable. In that fertile soil, my love for a certain type of art grew. Art smeared in mud and blood. Art that’s impolite. That surprises with its capacity for pain. That shocks and triggers us—as Roland Barthes described the punctum in his favorite photographs, in Camera Lucida—with a “sting, speck, cut, little hole.” When I got older, I realized there’s a name for this aesthetic.

The famous lecture, “Juego y teoría del duende” (“Theory and Play of the Duende”)—which Lorca wrote, by hand, while on board the transatlantic ship Conte Grande, and presented at a conference in Buenos Aires, October, 1933—is about a goblin called duende. He explains that duende is not an angel or a muse, both of which are far too polite, but rather, a “mysterious power.” A goblin that “will not approach at all if he does not see the possibility of death, if he is not convinced he will circle death’s house.”

I knew this goblin. I felt the frisson of it passing through me while listening to Merry Clayton’s voice as it cracks on the word “murder” in the Rolling Stones’ “Gimme Shelter.” In the Sex Pistols’ jarring, driving guitar in “God Save the Queen.” In Jimi Hendrix’s rendition of “The Star Spangled Banner” at Woodstock: that warped national anthem morphing into an onslaught of bombs dropped on Vietnam. In Nirvana’s MTV Unplugged performance of “Where Did You Sleep Last Night”: out of the whining lover Cobain, the howling cuckold duende suddenly bursts forth.

In Dennis Hopper’s middle finger at the rednecks who shoot him.

It’s the goblin that entered Emily Dickinson’s room when she felt “physically as if the top of [her] head were taken off.”

*

Lorca respected fear, anger, anguish, joy—the range of raw human feelings—but scorned reason: “Intellect is oftentimes the foe of poetry,” he said, “because it imitates too much, it elevates the poet to a throne of acute angles and makes him forget that in time the ants can devour him, too, or that a great arsenical locust can fall on his head.” Intellect might capture a thin notion of strife, but the goblin inhabits the struggle bodily. “The duende . . . is a power and not a construct, is a struggle and not a concept. I have heard an old guitarist, a true virtuoso, remark, ‘The duende is not in the throat, the duende comes up from inside, up from the very soles of the feet.’”

The speaker of Lorca’s four-part elegy, “Lament for Ignacio Sánchez Mejías”—brokenhearted over the death of his close friend, a famous matador who died in the bullring in 1934—gushes with grief and longing and song. Trapped in his wound.

I will not see it!

Tell the moon to come

for I do not want to see the blood

of Ignacio on the sand.

I will not see it!

The moon wide open.

Horse of still clouds,

and the grey bull ring of dreams

with willows in the barreras.

I will not see it!

Let my memory kindle!

Warm the jasmines

of such minute whiteness!

I will not see it!

The cow of the ancient world

passed her sad tongue

over a snout of blood

spilled on the sand,

and the bulls of Guisando,

partly death and partly stone,

bellowed like two centuries

sated with treading the earth.

No.I do not want to see it!

—from Part 2, “The Spilled Blood”

I will not see it!

He wants the moon to come to take away the terrible vision of Ignacio’s blood. With the moon comes a dream of a monolithic cow lapping the bullfighter’s blood with her “sad tongue.” The pain is overwhelming, for him and for us. His exclamation, “I will not see it!”—evoking the women belting out siguiriyas, and the “headless Dionysiac scream” of Merry Clayton—is a kind of jaleo: a chorus in flamenco in which dancers stomp their feet and singers shout and clap their cupped hands to the rhythm of the song. It’s also the Olé, Olé! of bullfights. Lorca’s poems, with their repetitions and cries, are often sung to music.

“Lament” is one of Lorca’s most famous poems, perhaps because the suffering reaches such a dramatic pitch. It’s sincere, surreal, and intense. Its form borrows from ancient Hispano-Arabic tropes rooted in Andalusian culture: It’s musical, repetitive, cryptic. Lorca’s aesthetic stemmed from his worship of the “deep song” of the Spanish gitanos, or Roma people. “The Roma,” he said, “is the most basic, most profound, the most aristocratic of my country, as representative of their way and whoever keeps the flame, blood, and the alphabet of the universal Andalusian truth.” Lorca cherished bullfighters, flamenco dancers, and gitano motifs like horsemen, wolves, honey, olives, blood on the lips, a knife in the heart.

Certainly a film like Carmen (1983)—director Carlos Saura’s flamenco adaptation of Bizet’s famous opera—feels like it “comes up from inside, up from the very soles of the feet.” In a seminal scene, called La Tabacalera, two women—ferocious Carmen and Cristina—duel with knives, taking long steps back and forth, singing and holding eye contact with each other, like wolves. “In this factory,” sings Cristina, “there are more bitches than good girls.” Carmen—after replying “Don’t you annoy Carmen!”—grabs a knife from a table and cuts Cristina’s throat.

*

Tracy K. Smith, in her essay “Survival in Two Worlds at Once: Federico Garcia Lorca and Duende,” argues that we poets can’t assume that the goblin will roost in our art. If there’s duende in our poems, it’s a happy accident, a result of living in such a way that makes the goblin curious enough to visit. She loves the concept of duende, she says,

because it supposes that our poems are not things we create in order that a reader might be pleased or impressed . . . we write poems in order to engage in the perilous yet necessary struggle to inhabit ourselves—our real selves, the ones we barely recognize—more completely. It is then that the duende beckons, promising to impart “something newly created, like a miracle,” then it winks inscrutably and begins its game of feint and dodge, lunge and parry, goad and shirk. . . . You’ll get your miracle, but only if you can decipher the music of the battle, only if you’re willing to take risk after risk.

If we write poems that face our unique struggles, attempting to find “our real selves,” duende might grant us a “miracle”: that is, the poem. Duende, it seems, doesn’t care who the artist is or what the artist believes, but only that the work reeks of human struggle. Of feelings exposed. Of the “bare, forked animal” smeared in blood and mud.

In a poem Jack Gilbert remembers a woman at a long-ago barbecue: not her name or face, but how, after tearing into a piece of meat, she “wiped the grease on her breasts.”

Duende is also a useful panhandle for helping us, as critics of art, to find language to “pick up” unwieldy, ineffable work. As we talk about duende, the discussion moves away from the “genius” of the artist and toward what the artwork gives off, as if of its own accord. Picasso was brilliant, sure, but not all of his work has duende.

The discussion moves from psychology to myth: as the painter paints, the goblin creeps in the nearby shadows, waiting to catch a whiff of the deep song. If it isn’t drawn to the work, it creeps away.

*

The Polish film, The Cremator (1969), directed by Juraj Herz, is a deeply unsettling comedy. The main character, Karel Kopfrkingl, is a quirky fellow who works at a crematorium in Prague in the 1930s. At the start, he simply takes his job too seriously. Then he begins collaborating with anti-Semites, killing off his family, and by the end he turns into a mass murderer who runs the ovens at Nazi extermination camps.

The original novel by Ladislav Fuks that caught Herz’s eye is called Spalovač mrtvol—The Burner of Corpses.

Lorca tells us that duende will not come to the artist “if he can’t see the possibility of death.” But what do we, as artists, know about death?

The director, Herz, was Jewish. A concentration camp survivor.

*

For the first hour of The Cremator, I could feel a grin on my face. It’s satirical, funny. Kopfrkingl has a big round bland head, with a wry Peter Lorre grin. By turns playful, lascivious, murderous.

Herz’s milieu is experimental: Czech New Wave. Faces are shown too closely, with creases and sweat. Kopfrkingl loves to stare into a convex mirror and chat to himself. The film is a kind of long inner monologue by Kopfrkingl, interrupted a few times by others. Scenes blend into one another through Kopfrkingl: zoom in on his face at a restaurant, pan out in a store of mirrors. The framing decisions—by Herz and cinematographer Stanislav Milota—are eccentric: juxtaposing Kopfrkingl and his family with animals in a cage. Extreme close-ups, fish-eye lenses, restless inter-cuts. All stark black and white.

Kopfrkingl is likable, to a degree. It’s fun to follow him as he cleans his ears, drums up business for his crematorium, flirts awkwardly with a young woman who works at the crematorium, visits a brothel, listens to Dvorak at full blast. Always with his little grin. He’s a creepy dude with a sense of humor, like someone we knew in high school. A morbid Everyman.

His wife Lakme, who watches Kopfrkingl with increasing astonishment, goes along with everything he does right up until he hangs her from the bathroom ceiling.

Kopfrkingl carries around a cumbersome book about Tibet, with a photo of the Potala Palace in Lhasa on the cover. He has a vague notion that as a cremator he helps liberate souls. “In seventy-five minutes,” he purrs, “Miss Čárská will be turned to ashes and fill her urn. But not her soul. That doesn’t go in the urn. It will be liberated. ‘Reincarnated,’ as the Tibetans say. It will rise up into the ether.” In a baroque ballroom, to well-dressed old folks, he delivers a speech about funerals:

Such a crematorium, dear friends, is pleasing to the Lord, helping him to hasten our transformation into dust. Some people object . . . saying Christ was buried, not cremated. But that’s quite another matter. I always tell those good people that they embalmed Our Savior, wrapped him in linen, and buried him in a cave. But no one will bury you in a cave or wrap you in linen . . . . [W]e live in a good and humanitarian state that provides crematoria . . . so that, after life’s many tribulations, people may lie down and turn quietly to dust.

Kopfrkingl is followed throughout the film by Death, in the form of a young woman with long black hair parted in the middle. In the final scene, Kopfrkingl is being driven in the pouring rain toward his future role with the Nazis. While he sinks deep into his delusion (“No one will suffer,” he says, “I shall save them all”), the female apparition—who’s kept her distance, watching him impassively—breaks into a mad sprint after his car.

Out of the Prague rain, Potala Palace materializes before the car, growing bigger, as if Kopfrkingl were arriving there. A chorus of ethereal angels sing. Konec, finis, the end.

*

Duende requires a transformation. An ethos disrupted. For Herz, Kopfrkingl is an agent of change. At first he’s just a petit-bourgeois oddball. He takes his wife and children on an excursion to a carnival, where he visits a wax museum exhibiting grisly murders, severed heads, body parts. “What a scourge,” he says, staring at each diseased body, his eyes bright with excitement. An old friend of his, Reinke, plants the seed that Kopfrkingl’s blood is German and not Czechoslovakian. Soon after, Kopfrkingl’s delusions of grandeur turn to antisemitism. He—initially a doting father, then cold and aloof—turns against his partly Jewish family. We watch his megalomania slowly transform into Nazism.

The goblin mutates, shifts, restless, protean, a river reflecting light. Hendrix’s guitar whining the national anthem, then bursts with bombs upon Saigon. Kopfrkingl himself, in keeping with his idea of death and the embalming of Christ, transforms the people around him “into dust” before our eyes. We see a ripple effect around him: Prague is pitilessly altered by his presence.

Lorca described duende’s power of transformation in a parable:

Some years ago, in a dancing contest at Jerez de la Frontera, an old lady of eighty, competing against beautiful women and young girls with waists as supple as water, carried off the prize merely by the act of raising her arms, throwing back her head, and stamping the little platform with a blow of her feet; but in the conclave of muses and angels foregathered there—beauties of form and beauties of smile—the dying duende triumphed as it had to, trailing the rusted knife blades of its wings along the ground.

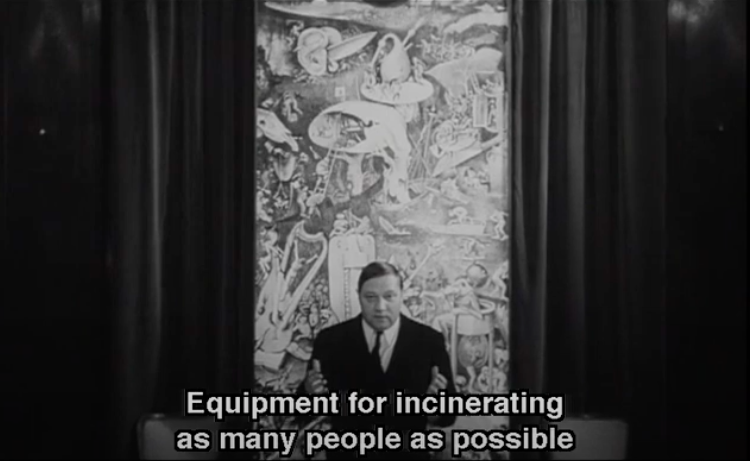

By the end, Kopfrkingl has morphed into a vision of terror, solidified by a moment of unforgettable framing. He stands in the elaborate office of a Nazi superior who offers him a job as technical supervisor for the “gas furnaces of the future.” The camera, slowly panning a long mirrored table, arrives at Kopfrkingl in front of an enormous painting: the right panel of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, with its graphic depiction of hell.

In fact, not in front of that grotesque nightmare. Within it.

*

Aesthetically speaking, a wound needs a body.

The painter Francis Bacon would have agreed, I think. Although Bacon lived in an era ruled by abstract expressionists such as Willem de Kooning and Barnett Newman, his work remained stubbornly literal.

Bacon shows us bodies in jeopardy. His paintings—the vulnerable and brutal human figures, the guns, nails, syringes, raw meat—are involuntary convulsions, mutilations, as in the grainy horror films of the ’70s such as Eraserhead, Halloween, and Carrie. “The entire series of spasms in Bacon,” says Gilles Deleuze in Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation, “is of this type: scenes of love, of vomiting and excreting, in which the body attempts to escape from itself through one of its organs in order to rejoin the field or material structure.”

While figures painted by certain artists—such as Chaïm Soutine, whose The Page Boy at Maxim’s (1927) depicts a misshapen blood-red bellboy with blacked-out eyes—seem to want to turn themselves inside out, Bacon’s figures, in the psychic space he allows them, actually do twist inside out.

Have you ever seen those guilty dog videos on YouTube, where the dog has eaten an entire pizza off the table, and their human is waving the pizza box, taunting the poor creature—“Did you do this, boy? Did you?”—and the dog is so mortified that it bares its teeth and distends its face, as if trying to climb out of its own face?

Imagine that grotesque shame, that desire to escape violently from oneself, taken to a pathological degree, and depicted on canvas over and over for a lifetime.

*

In Bacon’s Study for a Self-Portrait (1964), a figure sits on a bed in a painfully strained, contorted position. The painting emanates a violent, eerie otherness. As viewers, we have a natural impulse to empathize with a figure in pain. To console them. Bacon disrupts these impulses, which creates tension, struggle. First, the figure in Study for a Self-Portrait is two people: Bacon’s head and Lucian Freud’s body. Second, as the title reveals, it’s not a self-portrait but a Study for a Self-Portrait. Third, the room contains characteristically impossible elements: namely, a bizarre black box hovering in the air behind the head, with a spatter of sinister black mist around it.

Perhaps Bacon, by creating this triple-otherness, is revealing what an alien experience it was for him to look at himself. “It is not I,” Deleuze says, “who attempts to escape from my body, it is the body that attempts to escape from itself by means of . . . in short, a spasm: the body as plexus, and its effort or waiting for a spasm.”

What captures our attention, foregrounded by the impossible box, is the face which seems to be attempting to turn itself inside out. The goblin is everywhere in the room, but surfaces—as if climbing out of the body to greet us—from that face which, like Kopfrkingl in front of the Bosch painting, transforms or, yes, spasms before our eyes: the left side red and pink, the right disintegrating into ash. Broken, twisted, nightmarish. Bacon’s dream of Lynch’s Elephant Man. That riveting face is our focus. The locus of struggle and transformation. “The shadow,” as Deleuze says, “escapes from the body like an animal we had been sheltering.”

Bacon wants us transfixed by the disaster of the face. He gives us no reprieve. No out.

The background of Bacon’s painting—the bed, walls, room—is just a suggestion, an outline designed to draw our eyes over and over and over toward the face that writhes before us. The goblin requires instability and struggle, which, in this painting, manifest in the grotesque face.

As viewers we long to avert our eyes but can’t. We are stuck—like the painter himself, perhaps—in a space of ruthless and harrowing interiority.

*

Once we’ve viewed Bacon’s work, it’s hard to shake the ghastly trauma of it.

I wonder, does the traumatized artist, seeing the wound wherever they look, project it onto their work for the rest of their lives? Frida Kahlo said, “I don’t paint dreams or nightmares, I paint my own reality.” If Bacon was doomed to repeatedly paint his traumatic reality, how can such work be cathartic or uplifting for us viewers?

For the traumatized person, as Bessel van der Kolk describes in The Body Keeps the Score, trauma remains in present tense: “Being traumatized means continuing to organize your life as if the trauma were still going on—unchanged and immutable—as every new encounter or event is contaminated by the past.” When a traumatized soldier is triggered, an explosion feels like it’s happening over and over, right now.

If an artist is stuck in a cycle of trauma, perhaps hiding it from themselves but allowing it to surface in their artwork, is that a healthy process for the viewer, who experiences what the art expresses by proxy, like secondhand smoke? Is the headless Dionysiac scream of Silverio’s Siguiriya good for us?

Is it perhaps useful for us, since so many of us are traumatized, to experience the trauma of another in the comparatively safe space of a work of art?

Is there a toxic goblin and a non-toxic goblin? What would Lorca say? Certainly Bacon’s paintings fit Lorca’s criteria for duende: They’re gritty, death-haunted, irrational, with a smidge of the fiendish or unholy. Would Lorca argue that the flamenco chorus that shouts and claps the jaleo is purer, sweeter, more spiritual than Bacon’s monstrous twisted figures?

In all Andalusia, from the rock of Jaen to the shell of Cádiz, people constantly speak of the duende and find it in everything that springs out of energetic instinct. That marvelous singer, “El Lebrijano,” originator of the Debla, observed, “Whenever I am singing with duende, no one can come up to me.”

To my ear, the ethos of this “marvelous singer” sounds sweeter than that of Bacon’s paintings. But, at their base, haven’t El Lebrijano and Bacon both tapped into the same “energetic instinct”?

Or are these the wrong questions? Perhaps we should ask, Does artwork need to uplift us, or can it just be what it is, even if it’s grotesque, degrading, painful?

*

And which of the goblin’s myriad forms will appear in our own artwork?

“The duende,” says Lorca, “works on the body of the dancer like the wind works on sand. With magical force, it converts a young girl into a lunar paralytic; or fills with adolescent blushes a ragged old man begging handouts in the wineshops.”

Had my mother not read me the gruesome Roald Dahl story, would I have written one terrifying swan poem after the next?

A man kills a swan at a public park, stuffs the limp corpse in his backpack, serves it to his friends for dinner, saying it’s chicken. Years later he revisits the park with his daughter, as the miserable dead watch from a nearby building. His daughter is under a spell at the edge of a pond, as a large swan emerges over her. She and the swan are screaming.

Leda is minding her business at a lake when a swan surges above her like an alien mothership, a Manhattan-sized chandelier shimmering with owls and goblins and at the center is Leda herself, her brightest self, black hair, eyes furious. And this gyring swan-earthquake rumbling out of the past toward eternity enters her.

You’re trying to tell me you don’t think of swans as nightmare creatures?

*

Poems with duende are wolves among us. The Biblical expression “wolf in sheep’s clothing” is meant to warn: “Beware of false prophets.” Stay away from bad teachers. Be careful, don’t listen.

But the goblin—far from a bad teacher—is truth on wheels. A sibyl in the living room.

We are so used to hearing the same ideas told in the same ways over and over, Baaa baaa baaa, that when the goblin arrives in sheep’s clothing, it speaks a language so fresh we almost can’t register what it’s saying. Language supercharged with the energy of a god, like Zeus in his horrible bird costume.

A line trots up to me sidelong in the field and sings—

Brag, sweet tenor bull, / descant on Rawthey’s madrigal, / each pebble its part / for the fells’ late spring.

—Basil Bunting

Some lines knock me over as I’m munching the grass—

In tenth grade, I kissed a guy who called me a faggot once or twice a week. / I still see his voice: / six hummingbirds nailed to a wall.

—Eduardo C. Corral

Some lines shiver with guileless fragility—

Yes, Father! Yes, and always, Yes!

—St. Francis de Sales’s prayer

Some lines bleat like all the sheep at once—

In the increasingly convincing darkness / The words become palpable, like a fruit / That is too beautiful to eat.

—John Ashbery

Some lines sound like the shepherd—

And now it seems to me the beautiful uncut hair of graves

—Walt Whitman’s answer to the child who asks, “What is the grass?”

And some lines sound like the field—

A rotted swan / is hurrying away from the plane-crash mess of her wings / one here / one there

—Alice Oswald

*

The first time I heard the recording of Amiri Baraka reading “Dope” was at a local workshop on Baltimore Avenue in West Philadelphia. Poet Warren Longmire played it for us. A long silence followed. Here’s the beginning:

uuuuuuuuuu

uuuuuuuuuu

uuuuuuuuuu uuu ray light morning fire lynch yet

uuuuuuu, yester-pain in dreams

comes again. race-pain, people our people

our people

everywhere . . . yeh . . . uuuuu, yeh

uuuuu. yeh

our people

yes people

every people

most people

uuuuuu, yeh uuuuu, most people

in pain

yester-pain, and pain today

(Screams) ooowow! ooowow! It must be

the devil

(jumps up like a claw stuck him) oooo

wow! oooowow! (screams)

We hear the joy of the exclamations (“ooowow!”)—so much like the Olé! and claps of the jaleo—

which also sound like cries of pain from living in a Black body in America. Wound and celebration together.

Baraka echoes the voice of an Uncle Tom-like Black parishioner sermonizing on the violence against their community. Rather than blaming the real culprits—white folks, politicians, the news, apartheid, imperialism, capitalism—the poem’s speaker says, “It must be / the devil,” and gaslights the community itself. By taking on the voice of an undiscerning churchgoer, Baraka indicts the complacent values of the church: “yessuh, yessuh, yessuh, yessuh, / put yr money in the plate, dont be late, dont / have to wait, you gonna be in / heaven after you die . . .”

The title “Dope” suggests illegal drugs, such as cocaine, brought into poor Black neighborhoods by the CIA in the ’80s, resulting in the addiction and imprisonment of many, especially Black men. This is just one in a multitude of insults the Black community has endured since the first ships sailed here from Africa. It’s the original sin of America. The ungraspable emotional truth of the last four hundred years.

For a poet like Baraka, I think, art was a way to broach a subject that’s so hot it feels like it will burn us alive if we touch it. The duende of Baraka’s poem, or what the duende speaks to, is slavery. Giving voice to the struggle of Black Americans, Baraka empowers the goblin, as Lorca says, “to baptize in dark water all those who behold it.” “Dope” certainly does not exonerate those who “behold” it, but provides a kind of shadow of the original experience, leading the reader, one would hope, toward empathy and commiseration. For us viewers, art is a way to hold, so to speak, the violence and horror of the world: that is, to experience it in a way that won’t destroy us. We can—if we’re lucky enough to live free, to some degree, from the turmoil that so much of the artwork I’ve cited describes—close the book, turn off the TV, walk out of the cinema, go about our day. We can sometimes even grasp an emotional truth that’s been eluding us.

*

Although we can certainly talk about the goblin, it eludes definition. If duende has a form, it’s not, as Lorca makes clear, any of the tropes we’re familiar with:

. . . I would not have you confuse the duende with the theological demon of doubt at whom Luther, on a Bacchic impulse, hurled an inkwell in Nuremberg, or with the Catholic devil, destructive, but short on intelligence, who disguised himself as a bitch to enter the convents, or with the talking monkey that Cervantes’ mountebank carried in the comedy about jealousy and the forests of Andalusia.

Here—to comic effect—Lorca tells us what duende is not, employing via negativa, the mode that John of the Cross used to describe the divine.

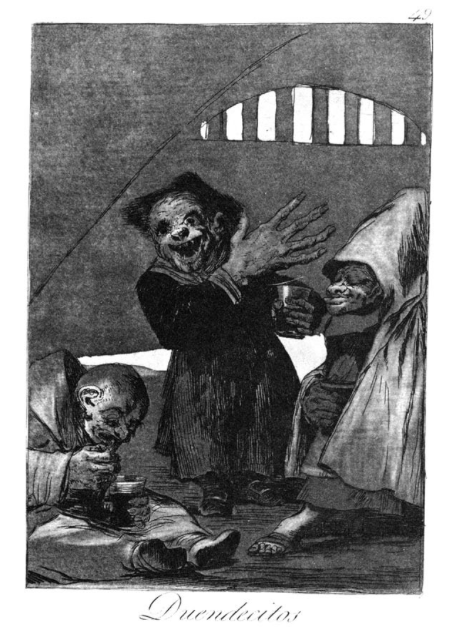

Lorca tells us duende is a winged goblin that can fly, but he warns anyone foolish enough to try to pin it down further that there is “neither map nor discipline.” His fascination lies in those possessed by the goblin. “Enough to know that he kindles the blood like an irritant, that he exhausts, that he repulses, all the bland, geometrical assurances, that he smashes the styles; that he makes of a Goya, master of the grays, the silvers, the roses of the great English painters, a man painting with his knees and his fists in bituminous blacks . . .”

The goblin arrives through people, not in front of them. More poltergeist than monster. We can’t know its specific form, but we see it appear—fluidly, over and over again—in what we fear, and where that fear ignites into inspiration.

For each of us it manifests differently. For Nick Cave, as violent cowboy songs. For Juraj Herz, as Kopfrkingl and his female death shadow. In Mayan and Mestizo folklore, as a three-foot tall creature—ugly, stumpy, hairy, thumbless, feet pointing backwards—called Tata duende.

In a poetry workshop, a student of mine once said duende reminded them of Jenova Chen’s 2008 video game Flower. I looked it up. The player drifts across a vast open world, touching flowers that burst into blossom, transforming a desiccated desert into a pastoral jungle. I think Lorca would have liked it.

Over a beer one evening with the poet Zach Savich, he asked me softly, “Duende? Is that when a shadow falls across a thing?” That stuck to me. For, yes, a shadow does not make a thing disappear, but just casts it in a different light. If darkness is death itself, a shadow is just a hint, or vision, of death. The shadow, falling across a thing we thought was ours, shakes us from our dream of invulnerability and eternal life, reminding us that everything around us—car, house, country, family, possessions—is transient. Perishable.

And in that shadow of fear and denial, the goblin giggles and twirls and prances and stomps his feet. As if mocking us!

John Wall Barger’s sixth book of poems, Smog Mother (Palimpsest Press), came out in the fall of 2022. His book of lyric essays on poetics and cinema, called The Elephant of Silence, is coming out in spring 2024 with LSU Press. He’s a contract editor for Frontenac House, and lives beside a river in Vermont.

This post may contain affiliate links.