I was prone to strep throat as a child, and I feel strongly that a sore throat is the worst symptom of our minor illnesses. It’s a small indignity that interferes violently with the mechanics of life, making it hard to eat, drink, swallow, talk. It is literal and metaphoric at once—to lose one’s voice.

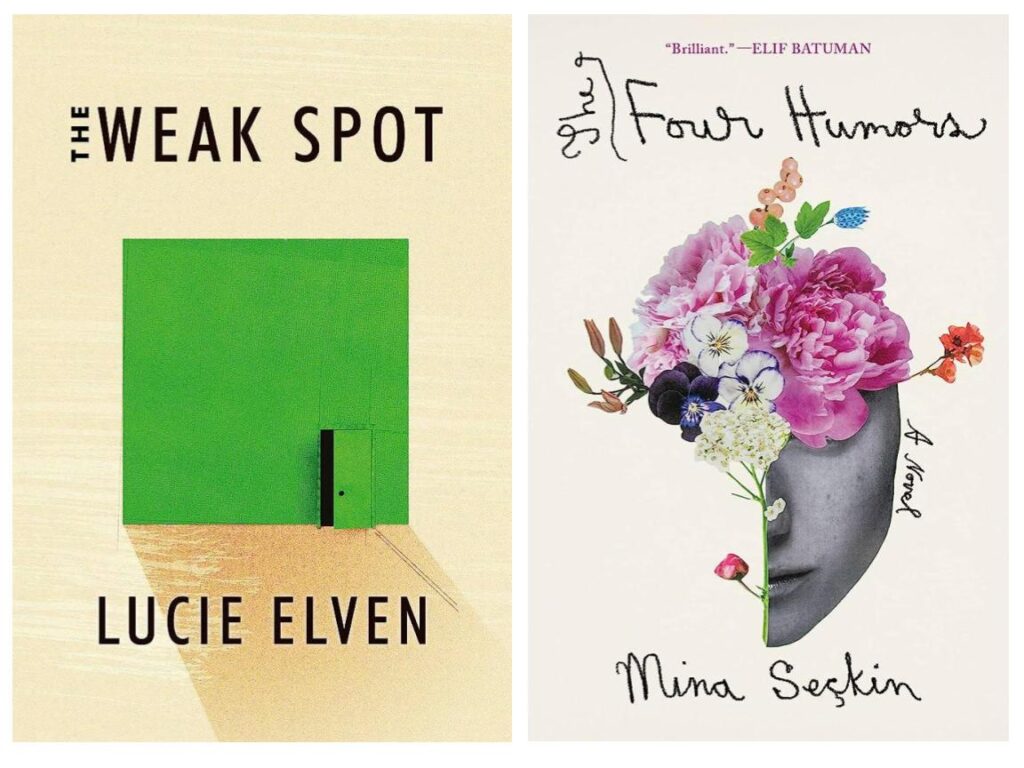

There are so many ways to be vulnerable, to be weak, in the throat. It is where language leaves the body, where the body is given voice. But it is also the place where language can be trapped, where secrets can fester. To expose one’s throat to a stranger is to leave oneself vulnerable; it’s an accident or an offer, a slip up or a sign of trust. This dual physical and linguistic vulnerability is taken up as a theme in two recent novels, Lucie Elven’s The Weak Spot and Mina Seçkin’s The Four Humors. The novels, of course, differ in tone and scope. Elven’s slim and magnetic novel reads almost like a fable about a remote mountain town whose quaint charm cannot conceal its foreboding, whereas Seçkin’s novel is a sweeping, intergenerational saga about sickness and secrets. But, in both, the images that linger and serve as keys to the novel’s thematic concerns are of throats damaged and destroyed. Elven’s mountain town is haunted by tales of a beast that was said to roam the novel’s remote mountain setting centuries ago—killing girls, devouring them throat-first. Seçkin’s narrator, Sibel, cannot stop thinking about the throat of a mysterious woman she sees at her father’s funeral—there is a hole in it from a tracheotomy, “black and big as a quarter.”

In Elven’s novel, the titular “weak spot” is the throat, first literally, then metaphorically. The unnamed narrator is a pharmacist, newly arrived to apprentice in a small town accessible only by a funicular run by a man referred to, whimsically, as Mr. Funicular. The narrator’s new boss, Mr. Malone, has peculiar methods. He “believed that a pharmacist’s role was to enhance the locals’ potential by listening skillfully,” treating the maladies they come in for by collecting details about their lives and providing his own explanatory narrative—a sinister kind of narrative medicine. Very little is sold and very few prescriptions are written at the pharmacy. Instead, Mr. Malone gathers the trust the townspeople come to place in his version of events and stores it for future use. Their dependence on him fuels his desire for control and its natural outlet, his small-town political ambitions.

The narrator, at first, resists this approach, following her more conventional training. But, gradually, her boss wears away at her certainty. “By the end of one month,” she notes:

I decided I had no ego left. I could be swayed by this or that person, because no part of me resisted being disturbed. Like a contortionist threading her fillet of a body through her arms, I automatically climbed into the customers’ perspective. I doubted myself constantly, wondering what I had forgotten, and what I had accepted as truth by repeating it.

This self-doubt comes to a head after the narrator suggests a medication to a woman in town, and Mr. Malone tells her that this recommendation has put this woman in the hospital, her throat swollen shut.

Several weeks later, when the narrator visits the afflicted woman in the hospital, the woman, Helen, tells her that she became sick long after she stopped taking the medicine; it was just that “her throat had always been her weak spot, that from a young age she had caught colds, lost her voice, had swellings, allergic reactions, tonsillitis, glandular fever, and even once a cyst on her voice box that had declared itself after a period when she had been working too hard.” This incident is a turning point for the narrator; she never quite trusted Mr. Malone or his methods and while now she resents him for making her feel guilty over Helen’s condition, she no longer trusts herself, either. She is not sure what version of events to believe, what is real and what is merely a story.

Later, the narrator begins to borrow Helen’s phrase with customers, in order to deflect from the “mute feeling” she knows she is giving off. She is not convinced by Mr. Malone’s stories, not really, but his stories and distortions sit uneasily with her, rendering her too unsure of the truth, and of herself, to speak freely. “I have a weak spot,” she tells the customers instead, “a magic phrase that I used to trick my way out of an emotional hole, glossing over my blues. It’s this or this or this.” She begins saying anything to avoid having to say something true; she has lost her ability to be sure what the truth of her life even is. Helen’s physical weak spot becomes the narrator’s metaphorical one—the narrator, unable to speak her experience aloud, unable to articulate the pernicious effects of Mr. Malone’s control of narrative, may not have had her throat swollen shut, but the truth is trapped there just the same.

And indeed, this is typical of Mr. Malone—another pharmacy employee explains that she would have strange and disturbing interactions with him in the evenings and then, “[i]n the morning, he provided a different memory for her to remember.” As the novel unfolds, it becomes clear that the mythical beast that lives in the mountains is personified in Mr. Malone—separating women from their stories, exploiting the vulnerability of the voices in their throats.

In The Weak Spot, the throat seems uniquely vulnerable: Helen’s illness is sharply defined, while the pharmacy’s other customers have various vague maladies. The Four Humors, in contrast, is a compendium of bodily ailments. Sibel, the narrator, travels to Istanbul to spend the summer with her grandmother. While there, she is supposed to study for the MCATs and visit her recently deceased father’s grave, but instead she obsesses over chronic headaches and suffers from severe menstrual cramps. She is also meant to care for her grandmother, who has Parkinson’s, but the boundaries between caregiver and cared for in their relationship are always shifting. The novel is structured around Sibel’s obsession with the ancient theory of the four humors: the idea that four bodily fluids—yellow bile, black bile, blood, and phlegm—account for the body’s condition, each fluid associated with different traits and tendencies. The novel is, then, preoccupied with the relationship between the somatic and the symbolic: It is about theories of health and healing, and the way these convert metaphors to medicine.

Within this framework, it is the damaged throats in the novel that literalize family secrets and silences, the things they don’t talk about. Sibel’s sister ruptures her esophagus vomiting; she has an eating disorder everyone in the family is aware of, but no one will discuss. At the hospital, Sibel learns that “the doctors think that if she hadn’t come in tonight, the fluid in her esophagus—saliva, food, vomit—could have leaked into her chest cavity, causing bacterial infection or abscess,” a sign that everything unacknowledged and undealt with cannot stay safely stuck in the throat forever.

And that is not the only thing Sibel’s family refuses to talk about. Sibel lies to her grandmother and her boyfriend about going to visit his grave. She is unable to properly grieve his death because she can’t understand his life; there is a hole in the center, like the hole in the throat of the woman from the funeral, whom Sibel can’t stop thinking about. For much of the novel, no one will tell Sibel who this woman is. When Sibel mentions her, her grandmother refuses to meet her eyes. When Sibel breaks up with her boyfriend, Sibel’s grandmother, accuses (not unfairly) Sibel of hiding too much, closing herself off:

She looks suspicious. I am worried, Sibel, about you. And about your openness.

Okay, I say, well, let’s talk openness. Are you still friends with that old woman? From the funeral?

She drops her keys. How many old women am I friends with, Sibel?

I try not to laugh, because this is serious. The one, I say, slowly, because we have never discussed this old woman. The one who spat at me.

I touch my throat.

The one with the hole, I add. From smoking.

My grandmother’s hand is shaking more violently than usual. She looks so tired today. I reach for her hand, but she bats me off.

Get dressed, she snaps.

I say yes, of course.

In the second half of the novel, Sibel’s grandmother finally begins to reveal the truth: Refika is her grandmother’s sister-in-law and, after Sibel’s grandfather died and against her grandmother’s wishes, Refika raised Sibel’s father as her own son. The two women haven’t spoken to each other in years.

Even before she knew this, Sibel could feel something hollow, the secret like a hole in the center of her understanding of her family—a hole like the hole in Refika’s throat. Once she learns the truth, she discusses it with her sister:

Alara mentions that it’s weird how Refika has never tried to meet us or talk to us. I say yeah, that is weird, although could we call spitting phlegm talking? Alara says hmm, very loudly and slowly . . . She says she can’t get Refika out of her mind and especially her throat.

This construction, “and especially her throat,” can be read two ways, suggesting both that Alara, like Sibel, cannot stop thinking about the hole in Refika’s throat, and that this new story is stuck in Alara’s throat as well. When Sibel finally meets Refika, she can see that it is indeed difficult for her to speak. Her voice, Sibel notes, is “quiet and raspy. I almost did not hear her.” The hole in Refika’s throat is both the physical source of her difficulty speaking and the symbolic representation of the silence that has spread between her and Sibel’s family. Before she tells Sibel about her father, Refika’s aid wipes the hole in her throat clean.

Elven and Seçkin both make use of the nature of the throat as the embodied and emblematic source of language and narrative. When your throat hurts, it is difficult to talk, and when there is something difficult to talk about, the words die in the throat. An injured throat represents the failure of narrative to cohere. In both novels, this failure is due to things rendered unspeakable. Elven’s narrator cannot speak her own story because Mr. Malone has offered too many other narratives, half-true and untrue. And Sibel does not know her family’s story because her loved ones refuse to speak their secrets aloud. The hole in Refika’s throat makes it literally difficult for her to speak and, symbolically, throats are damaged when stories can’t get out, when secrets go untold.

Both novels end when the central characters begin to resist this narrative incoherence. Elven’s narrator begins to reject Mr. Malone and his methods; she notes that his “descriptions of each person’s character and place in the town, which I had accepted because they were convenient and beautiful, were full of holes. His accounts of reality were unhelpful.” She has seen too many holes in his stories; the explanations that are his primary mechanism of control have ceased to explain anything. She decides to leave the town; shortly before she does, on a phone call with a trusted friend, she reflects that, after a few days of hardly speaking, “my voice sounded amazing.” By the end of The Four Humors, Refika and Sibel’s grandmother are beginning, tentatively, to speak again.

In both novels, the throat serves as machinery and metaphor; Elven and Seçkin each expose the throat as the locus of the possibilities and impossibilities of language, of narrating a life. Both use this idea to explore the way silence calcifies, denying the possibility of change or challenge. Whisper networks whisper for a reason: It is hard to speak into the face of power, of silence and its stories. It is hard because silence is worth something; in fairytales and folklore, a voice has tangible exchange value. But both Elven and Seçkin seem to argue that silence is impermanent, provisional. The secrets in Alara’s esophagus nearly leaked out; Mr. Malone’s stories ceased being helpful. The throat is the place where secrets can be trapped, but also the place where the experiences of the body become narratable. When I was a child, thankfully, my sore throats would only last a few days.

Meghan Racklin is a writer in Brooklyn. She writes about books and culture. Her writing has appeared in The Baffler and Literary Hub, among other places.

This post may contain affiliate links.