[City Lights Books; 2020]

“Before we start talking, I want to see how you understand the relationship between white supremacy and the police,” Linda Evans told me when we first hopped onto the call. I had set up a conversation with Lisa Roth and Linda Evans to talk about the 1980s, how they formed the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee, and what lessons those years had for today. Birthed as a sort of radical wing (or alternative to) the anti-Klan organizing that was happening coast-to-coast as a reaction to the revived KKK, the Committee took a slightly different direction than the organizations like the Southern Poverty Law Center and Anti-Klan Network (later the Center for Democratic Renewal). Instead their work was fueled by a series of conflicting impulses: to fight back against the violence presented by white nationalist organizing and to act on the convictions they had coming out of the New Left that white revolutionaries could best serve revolutionary ends by acting primarily in support of oppressed communities of color fighting for national liberation. What resulted could best be called an experiment, sometimes inspired and occasionally misfiring, as chapters of the Committee tried everything from physical confrontation to broad community arts events to stop the violent white power groups of the 1980s.

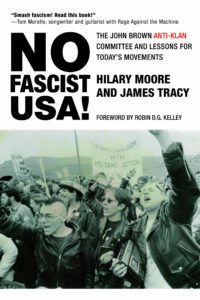

The new book No Fascist USA!: The John Brown Anti-Klan Committee and Lessons for Today’s Movements by Hilary Moore and James Tracy is an incredible chronicle of this journey, which starts decades before the organization’s founding and finishes today with the ways that the organization’s memory stays alive in antifascist strategies are used when facing the Alt Right. This would be a difficult project for a book of twice its length, but there is an effortlessness to the way that Moore and Tracy weave together complicating and competing political ideas, taking us through organizations like Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the Black Panthers, the Weatherman splits from SDS, the formation of the Black Liberation Army, the underlying revolutionary politics to the John Brown that were informed by a group called the May 19th Communist Organization, not to mention the wealth of history of the broader movements themselves.

As No Fascist USA! traces, the ideas that underskirted the creation of the Committee were more challenging than most of the white left has come to deal with. The organization formed out of the prison support many people were doing in New York to support imprisoned Black Panthers, and this work was central since they were prioritizing what they thought was the vanguard of revolutionary struggle and the “leadership from the oppressed.” The Panthers who were inside started reporting that the prison guards were organizing with the Ku Klux Klan, and white leftists doing the organizing on the outside simply didn’t believe them.

“We thought that they meant that the guards were really, really racist . . . ’I’m embarrassed to admit it now, we thought they were exaggerating,” said Lisa Roth, an organizer with the John Brown Committee who had begun her work with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) when she was still in high school. When they went to check the incorporation records for New York State they found that the president of the prison guards’ union was also the Grand Dragon for the New York Klan, and the prison guards were not only organizing with the Klan they were terrorizing black inmates, including staging cross burnings on the inside.

This led to a shift in how to perceive the role of the Klan, to see it as an insurgent and extra-judicially violent part of the police state that was engaging in a centuries long colonial war against communities of color, and a realization that it was important to organize white people to take on a primary role of the fight against both manifestations of white supremacy. “How to mobilize white people to fulfill that task was the central tactical question that animated the group. In the process, they encouraged white people to assume risks usually expected of people of color, including the risk of physical harm and ostracism. The group insisted that it was white people’s responsibility to get in the way of the threats posed by white supremacists. This approach was intended to undermine the age-old norms of white silence, complicity, and active participation in racialized intimidation, coercion, and violence,” writes Moore and Tracy.

This model created an implicit problem for the Committee as they were going forward with the work. It, in part, rejected the primacy of class struggle that people had normally associated with the left, instead viewing communities of color as the center of struggle, to be viewed, and supported, like national liberation movements abroad. White leftists were then not putting their own individual needs front and center, such as they would if they were organizing in their own workplaces, for example. Instead, their primary work was in support of others, and they were often asking white people to take on harder work with less glamorous outcomes. This approach to revolutionary struggle would openly reject the privilege of whiteness, and would require the white working class to join that struggle since racial division breaks apart the multiracial solidarity that would be necessary to truly confront the ruling class. This is a tough sell at any point, and particularly hard when the Committee hoped to create a mass movement of whites to take action against white nationalists.

This led to the group’s sectarian reputation, one that created problems for alliance building, as their complicated politics and strictly principled stances could stop recruitment. “We wanted revolution. If you only want revolution, then you don’t want reform, because it prolongs a system that has to go . . . The idea of no compromise was a flaw in our whole perspective,” said Committee member Julie Nalibov in the book.

One thing that was clear in my conversations with Committee members, and in Moore and Tracy’s book, is that the organization was fragmented and operated without centralized tactical choices. They did move members between locations based on the needs of local groups, but each chapter was going at things from a local context in an effort to see what worked. In Austin, Texas, Evans and others worked with the Brown Berets and anti-racist groups in large coalitions, first to stop the exploitative relationship that wealthy white boat owners had with communities of color set against a lake, but then later to confront racist policing and the paramilitary work of the Klan in Texas. This work evolved and included reconnaissance, which in the pre-Internet days of antifascist research meant often posing as interested white supremacist converts so they could meet with leaders like David Duke or Don Black, who were staging white supremacist militia training camps around the state.

In Washington, D.C., the American Nazi Party had rented out a public school to hold a meeting, and so the Committee acted as essentially the militant wing of the larger community push against the Nazis. While other groups, such as the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) or the NAACP wanted to use a “quarantine strategy” of ignoring them and staging counter-events off campus, the Committee thought they should push back. They had seen the success of recent mass actions in D.C. against the Klan, where thousands of people had come out to stop a Klan rally, and they wanted to use youth student power to do the same. This meant going where the teachers, parents, and nonprofit leadership wouldn’t go: directly to talk to the students. They ended up with a small rally where they physically fought back against the Nazis and Klansman, resulting in arrests and injury from the police. But, in a lot of ways, they had established their role. In Austin they worked in coalitions, where they could often be the more radical voice, to do counter-rallies against the Klan. And in Napa Valley they organized a mass action against “Aryan Woodstock” where they amassed hundreds amidst the rain and the distance from a city.

“We were completely reactive . . . The left does not get it on long-term strategic thinking,” Roth told me, and this was a critique she threw back at herself. “We never had a long-term strategic plan, and if we had we might not have the Alt Right today.”

Over time they wanted to push towards a more mass orientation, acknowledging that their militancy, which was committed to disruption by any means necessary, would not work without mass support. In Chicago they targeted recruitment directly at the same whites that the Klan was trying to recruit, getting them involved in projects to clean up racist graffiti or to sign letters saying they opposed white supremacy. In the Bay Area they set up a 5K run to raise money for their antiracist work, and created kits for kids in the punk scene to push back on racist skinheads. They saw the potential of antiracist skinheads in Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice (SHARP) and the Baldies, and were instrumental in getting Anti-Racist Action (ARA) off the ground. “We called them ‘adult groups,’” ARA founder Kieran Knutson once told me about groups like John Brown and the Center for Democratic Renewal. The young punks that would eventually form ARA were often coming out of a need to simply fight back and defend their community, they didn’t always have a strong leftist ideology backing their work at first. The John Brown Committee helped nurture that, to push them to go further and to validate their work as important, something a lot of other leftist groups simply were not going to do.

“There is so little emphasis . . . of what are the structural alternatives of what we have going here with our imperialist capitalist structure. I think, at that point, at least for us, we were actively trying to figure out what an alternative would be. So that put the actions that we were taking in a very different context. We were trying to encourage people to be militant so that they would realize that we could, and needed to, destroy this system and build something else,” Evans told me.

Evans was a character in another story, which is captured in the book and runs as an undercurrent to the Committee’s years. The Committee had already begun while Evans was doing time for the “Days of Rage” action, where the Weather collectives led a riot through the streets of Chicago in an effort to “bring the war home.” When she got out and moved to the South, she continued her revolutionary work, including with the May 19th Communist Organization (named for Ho Chi Minh and Malcom X’s shared birthday). She went back underground as part of a bombing campaign that supported the Black Liberation Army, and was eventually arrested and sentenced to life in prison aiding Marilyn Buck, a white collaborator with the BLA, then a fugitive, among other gun and “terrorism” related charges. She was eventually pardoned in 2000 by Bill Clinton as he exited the white house, which the book alleges could have been intended as a middle-finger to the Justice Department that had put so much pressure on the Clintons during the White Water investigation.

So the John Brown Committee had an inherent instability to it, a lack of a clear set of approaches or tools. But, in a sense, that was the point. Instead of deciding on an effective strategy and moving forward this was more an attempt to live out a committed political vision on another plane. The organizers involved had a certain clarity about what they thought the fault lines were, just not how to split them open, and they were willing to do everything, from hurling frozen sodas and gravel at Klansman to massive community coalitions for fundraising.

“Before this research, I couldn’t get the European-style of antifascism, and its ripple within the U.S., out of my head. But in charting John Brown’s path, I got to grow alongside the organization. Antifascism wasn’t just what I had seen at a few demos. The 13 year arc of the organization showed me that there are so many other moving parts. The JBAKC felt like a trustworthy organization to study because they changed over time based on what was most relevant — they never dropped militancy but they eventually chose tactics that were more inviting. They found ways for many more people to participate. And they made these changes based on long term connections to the strategies of liberation movements,” says No Fascist USA! co-author, Hilary Moore. “The organization is an important example in recent history where anti-racist white people formed an organization based on their political values and adjusted their tactics and strategies over time in response to shifting political conditions, particularly in a moment of accelerated white supremacist organizing within the US and globally.”

No Fascist USA! beautifully preserves the stories and characters in a way that flows well for the density of what it contains, but is also set up to inform actual organizing work. This is not dead history, it places the reader inside the continuity of its pages, hoping that the wins and losses of the Committee can serve as strategic information.

“I’m not sure that going underground was really that effective,” Evans told me, thinking about her time engaged in clandestine armed struggle. These questions haunt a group of people who were essentially life-long revolutionaries who never stopped organizing, even when sentenced to prison. What they are more concerned with now, rather than the rightness of their political positions, is how they are going to communicate to the broader community to invite them to join them. “Militancy needs to take place inside a plan if possible because people get really turned off and dismissive of the opposition.” says Evans. “If you have militancy without the mass politics, the masses aren’t going to support the militancy.”

The relevance of these points has even more salience today when the Committee’s claim that the armed white power movement were essentially adjuncts of the state is only more relevant as borders become militarized, deportations increase, and the White House refuses to code its nativism. How do you get the mass of white people to stage a revolt against whiteness?

“Today, it is clear that no one group of activists can push back against the far right on its own. An organization’s ability to amplify its impact through broad-based coalitions tactically advantages it over those unable or unwilling to do so for reasons of sectarianism and political righteousness,” says Moore and Tracy in their final chapter, which collects what they see as the key lessons of the John Brown Committee for today. There were blindspots (such as antisemitism), and there always are, and the former members will be the first to raise them since their tradition of self-criticism was formed around the idea that we can do better if we try.

And the sectarianism of the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee has been criticized heavily, but there is a kernel of inspiration there as well. It lacked pragmatism, which can lend itself to poor organizing choices, but usually stems from the deep commitment that comes from going deeper on issues than we often dare to. Antifascism today can be disconnected from struggles for decolonization, from the larger movement against police violence and in defense of black lives, or the environmental revolt on reservations, and for the Committee those things were always linked. So in this way their enduring legacy may be that white supremacy never stops with the neo-Nazis, even if you choose to start fighting it there.

Shane Burley is the author of Fascism Today: What It Is and How to End

It (AK Press, 2017). His work has appeared in Jacobin, Salon, Truthout, In These Times, Waging Nonviolence, ThinkProgress, Political Research Associates, Alternet, and Roar Magazine.

This post may contain affiliate links.