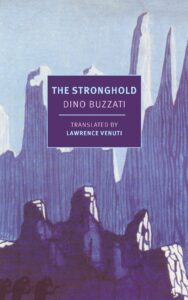

[NYRB Classics, 2023]

Tr. From the Italian by Lawrence Venuti

“Mystery lingered in the slant of the embankments, in the shadow of the casemates—an inexpressible sensation of future things.”

The Fortezza Bastiani stands at the center of Dino Buzzati’s The Stronghold. Originally published in Italy in 1940, this novel is a cautionary tale against squandering youth, a warning against ignorance. As its translator Lawrence Venuti highlights in his afterword, The Stronghold can also be viewed as a critique of Italy’s Fascist regime, the foolishness of men who follow orders without question, and the absurd callousness of their leaders.

The novel follows the life of Giovanni Drogo, a young officer who leaves home to take up his first commission at the mysterious, almost sentient Fortezza. As if in a fairytale, the Fortezza is hidden amidst treacherous mountains, from whose crumbling yellow walls Drogo is fated to spend the rest of his life surveilling what is known as the “Tatar Desert.” Permanent mists hang at the edges of this vast plain, and neither Drogo nor his fellow soldiers can imagine what exists beyond it. The reader never does discover exactly where the mythical Fortezza is, what the real name of the “Tatar Desert” might be, or the true identity of the exoticized enemy—the Tatars—against whom the soldiers are defending their borders. Even the novel’s temporal setting remains unspecified. Nevertheless, time passes swiftly for the men who serve at the Fortezza. Their short, expendable lives are set in sharp relief against the immutable, almost impassable mountains.

The Fortezza’s magic is conjured and sustained by Buzzati’s luscious imagery. Venuti’s meticulous translation projects the cinematic landscape that surrounds the Fortezza—the same landscape that Drogo traverses on the way to his new commission. At times, I almost felt like I was reading a painting. Drogo journeys alone on the “flank of the mountains, which grow increasingly huge and wild.” Later, as dusk falls, “violet darkness” fills ravines, and shadows “rise . . . quickly, from the depths, where a torrent roars.” Aside from his horse, Drogo’s solitude is complete, the only other living being is a bat as it “waver[s] against a white cloud.” When Drogo finally glimpses the Fortezza from afar, nature itself tries to warn him against continuing. In Venuti’s alliterative translation, “up over the ramparts burst the baleful wind of night’s abrupt arrival.”

To Drogo, the Fortezza Bastiani appears unreal:

Through a chink among the nearby crags already shrouded in darkness, behind a chaotic progression of peaks, Giovanni Drogo spotted a bare hill at an incalculable distance, still immersed in the crimson light of sunset, as if conjured by a spell. On its crest appeared a regular, geometric strip in an unusual shade of yellow: the profile of the Fortezza.

Once Drogo takes up his post, however, these expansive, color-rich descriptions are abruptly counterpointed by the language of military business, and the pettiness of men who have grown bored of the views around them. When he first arrives, Drogo is spellbound by the beauty of the landscape. When he is ushered towards a viewpoint in the Fortezza and finds himself gazing towards the mysterious north, we hold our breath as Venuti’s sonorous translation describes Drogo’s reaction, that “a limitless silence seemed to descend amid the haloes of dusk.” By the third chapter, however, Drogo’s world begins to be reduced to conversations about passwords, orders, and routines. At first, Drogo resists, wishing to return to his hometown, but the Fortezza lures him in and holds him tight.

The unidentified narrator pinpoints the exact moment when Drogo’s fate is sealed, and beyond which he will be unwilling ever to leave his post: “Don’t give it a second thought, Giovanni Drogo. Don’t turn back. Now that you have reached the edge of the plateau and the road is about to plunge into the valley. It would be foolish weakness.” After this tipping point, Drogo turns his attention away from the beauty of the desert and focuses instead on an infinitesimally small point in the vast plain in front of the Fortezza. Using a telescope that is eventually confiscated by his superiors (they do not want him to detect an actual, tangible enemy), Drogo imagines that he sees foreign troops constructing a road across the vast Tatar Desert. While he focuses on this one spot in the far distance, fifteen years fly past. The “eons” that Drogo once thought he had, are diminished to nothing, and his youth is gone.

The appearance of a foreign army would be both a justification for these men’s seemingly endless sentry duty, and confirmation of their manhood—what kind of men would they be without ever facing battle? Their seemingly pointless routines are given meaning by repeated rumors and resulting paranoia. We understand the absurdity of their position: The threat of Tatars crossing the desert is an unlikely one, and yet no soldier questions it. Even when, years into his service, Drogo discovers that this rumor about the Tatars has only been circulated to motivate the men, he still declines to leave. The Fortezza is now his only home.

Women scarcely feature at all, and when they do, they represent a more familiar version of home, highlighting Drogo’s solitude. While his potential fiancée talks to him of love, Drogo dreams of the Fortezza, and longs to be back there. In a heartbreaking scene, Drogo prioritizes the Fortezza over love and marriage, seemingly unaware of the choice he is making. Buzzati’s novel is, then, predominantly about men, men governed by rumor and fear. It reminded me of our own endless news cycles and the toxicity of social media, where the enemy is unknowable and intangible, but so often a galvanizing threat. The possibility of Tatars, or in fact anyone, attacking the Fortezza, are not the real danger. Instead, time, rumor, and misplaced trust are the ultimate foe. The “Tatars” simply represent an existential threat, an idea perpetuated by the those in power to keep their soldiers busy and, more importantly, under control.

Sarah Gear is a PhD student at the University of Exeter. She researches the influence of political bias on the commission, translation, and reception of contemporary Russian fiction into English. You can find her at @sgear23.

This post may contain affiliate links.