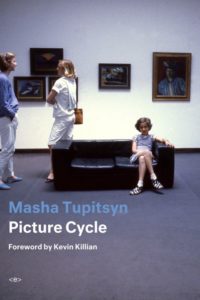

[Semiotext(e); 2019]

In the fall of 2016, I taught an introduction to film course at my graduate institution. The course was the first prerequisite for a film and media arts major or minor, but it also fulfilled one of the general education humanities requirements that all students had to complete. It was, as you might expect, a pretty full class, with a wide range of interests and expertise; a few cinephiles, and overwhelmingly more cine-curious, all convened in one space. Some were familiar with the way film criticism worked, but many were not. After weeks of watching and close reading various films, trying to pick through how they worked and what work they did for us — oftentimes without conscious knowing — some students expressed a frustration with me: surely learning how to read films in this way would ruin the joy of watching them in the first place. How could you have fun with a movie when all you did was try to figure it out? they asked. I wish I had read Masha Tupitsyn then, that I had Picture Cycle, her 2019 collection of a decade’s worth of writing about film, to show them. Because these essays manage to articulate something I could only vaguely gesture towards when my students confronted me with those frustrations: the best film criticism can only be done from a position of profound pleasure. That is, Tupitsyn’s essays show us that to write so thoughtfully, so eruditely, and so insightfully about the way films work, one must relish watching them; her criticism shows us that trying to figure out a film is some of the most fun you can have with them, because for Tupitsyn, watching and analyzing film has always been an embodied practice, a practice often rooted in the personal. For instance, there is one moment in the essay “Behind the Scenes”, an early memory — one of many that Tupitsyn interweaves into the text — which illuminates her intuitive critical eye emerging through childhood play. She describes the way she would psychologically embody films in order to play-act in worlds or scenarios outside of her own reality: “I’d mull over a part in a movie that I liked, wanted to grasp, be in. A movie that I’d circled and returned to for some unknown reason, a magnetic field pulling me, and then I’d draw that part back like a curtain.”

Picture Cycle is a rich text in part because it walks us through Tupitsyn’s development as a critic from the very beginning, like those early days of drawing back the curtain, to the present, where her prose and insight crackle across pages, still unearthing something magnetic about the films that she wants to grasp. It’s a text that shows us the whole range of a critic who has been trying to figure out movies and the people who make them since she was a child. “Famous Tombs: Love in the ‘90s,” the first essay of the collection, opens on a pre-teen Tupitsyn living across the street from new neighbors Johnny Depp and Winona Ryder. She recalls not-so-memorably running into Depp at the local deli and introduces what could be considered the opening salvo of the collection, a first stab at articulating one of the book’s myriad theses about the way film and media arts shape the way we see things: “You might not look at him unless you knew you were supposed to, which is really the singular difference between people onscreen and people offscreen: famous people are to be looked at.”

It’s a curious moment, one that makes you pause to consider the claim. It’s right, of course, famous people are to be looked at in a way that non-famous people are not. But across the subsequent essays, Tupitsyn troubles with what exactly it means to look at someone and what different methods of looking exist across offscreen and onscreen lives. As she excavates her own past, her lifelong relationship with film, and the way that the medium and its artifacts have changed over time, Tupitsyn challenges readers to consider looking as: seeing, knowing, decoding, identifying, surveilling, understanding, beholding, owning, creating, participating, remembering, listening, and recording. In shaping Picture Cycle as a kind of memoir-of-criticism, Tupitsyn offers the potential for a perpetually capacious cinematic gaze that reflects not only its changing technologies of seeing, but also for exploring the evolving ways of looking that audiences bring to that gaze over the course of their lives. The constant feedback loop of different lenses and screens — technological, yes, but also the sociocultural lenses and screens through and on which audiences desire, see, and project the various stories, fantasies, and images those technologies of cinema show them — is a perpetual story of reciprocity and change, one whose recursiveness Picture Cycle both describes in its wide-ranging essays and reflects in its patchwork form.

In another essay, “Analog Days,” Tupitsyn describes her relationship with a man named Fred, who she introduces as “[l]ooking for a woman who wasn’t me,” and then Tupitsyn reverses the gaze, declaring that “[l]ooking at him was like driving down a road”. She continues: “Fred had spent years watching me and looking back on it, I’d seen him do it…It took me a few minutes to recall his miscellaneous gazes.” These gazes are a type of looking, but they’re not the same looking that famous people invite or demand; they are gazes of intimacy, gazes unlike those reserved for Johnny Depp who, whether intentionally or not, begs to be looked at. And paradoxically, because of this hypervisible gaze, he is never truly seen as a person, but is seen only as and through the gaze of celebrity. But the gazes Fred reserves for Tupitsyn are almost entirely defined by their object’s relative obscurity. These gazes are notable precisely because she is not a celebrity, and is not constitutively meant to be gazed at. And thus these gazes mean something different, take on a different weight than those when, for example, looking at famous people.

Moving into the striking essay, “Everything Better Than Plot”, Tupitsyn describes another kind of looking: the work of the camera (and thus the viewer) as it watches the Three Kings in Albert Serra’s film, Birdsong, as they “trudge along languorously and aimlessly, with countless stop and lags in between” and learn “something about what it means to have lived then. To have moved from place to place. The energy it took — and the time.” And this looking is different still from that of an eight-year-old Tupitsyn in the essay, “I Touch Myself”, when she watches a closed circuit showing of a stage performance of her favorite heartthrob Ralph Macchio’s theatrical debut in Cuba & His Teddy Bear — which she describes as akin to “catch[ing] an actor in the act. There was no editing room to alter anything Ralph did. No cuts. No body doubles. No special effects…raw footage.” Or again compared to that in “On Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette,” where Tupitsyn discusses the absence of looking, and the performance of “not-seeing” that characterizes the societal rules of a film about, among other things, the necessity of not letting anyone else see you, see them, mocking you.

At the heart of these different ways of looking lies the idea that to look at something, to really look at it (which is, ultimately, what filmmakers do with their cameras so that we, as moviegoers, may do so) is to attempt to access something new, something real, something authentic. Why else do we look at each other, at things, at screens if not because we believe there is something to see there? Something worth seeing. What Tupitsyn sees when she surveys the wide range of filmic texts she explores in Picture Cycle’s pages — Pretty in Pink and Grease, but also The Usual Suspects, The Shining, a meditation on Robert Bresson, and everything in between — is dense and richly packed, ranging from what we see when we look at John Cusack, to the salience of the devil as a filmic representation of reality. There is something in this collection for everyone simply because Tupitsyn’s gaze seemingly knows no bounds and, luckily for us, it invigorates each subject upon which it touches.

Mary Pappalardo is a writer, editor, and teacher based in Ann Arbor. She has a PhD in English from Louisiana State University, and her writing has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Real Life, and others. She is an Assistant Fiction Editor at The Offing.

This post may contain affiliate links.