In February of 2020, UDP apprentice Paige Parsons sat down with Jena Osman to discuss her book Motion Studies (2019) at the author’s home in Philadelphia. In Motion Studies, Osman traces connections between nineteenth-century science and contemporary technologies, considering and interrogating multiple ways of knowing. In the book’s titular piece, Osman weaves together meditations of early studies of movement by the French physiologist Etienne-Jules Marey, fragments from popular films, and a speculative narrative in which two characters attempt to escape the surveillance systems that engulf their lives. In this interview, Parsons and the author discuss Osman’s process, her movement between forms, the continuous presence of history, and obsessions that endure.

Paige Parsons: I thought it would be nice to start with this line I wrote down from the beginning of Motion Studies—the first line in the book: “A small action sets off the ones to come. Someone finds a book in a library and is taken with the pictures” (13). Can you talk about the moment of small action that sets off this book?

Jena Osman: Do you want to see the book?

Yes!

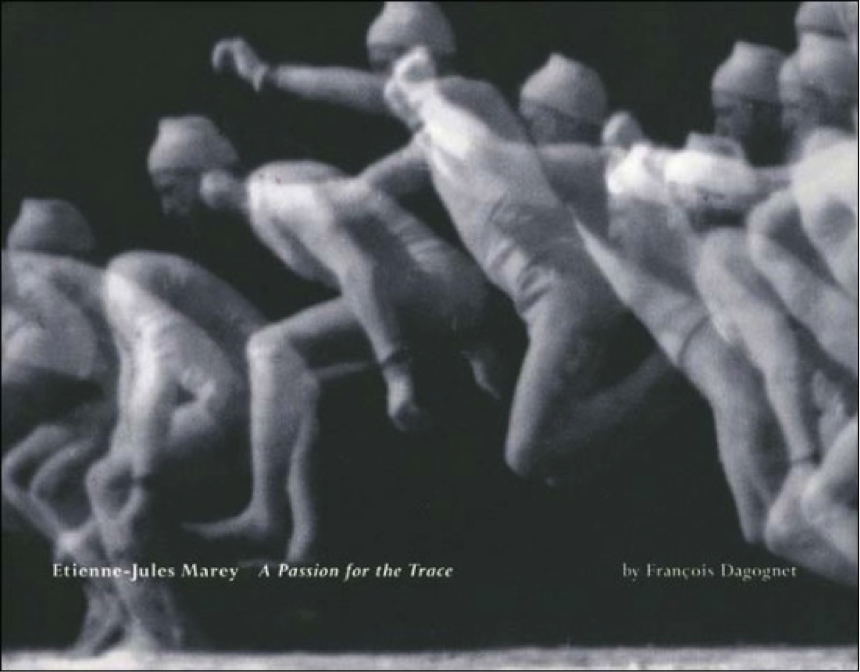

I’ll bring it down (goes upstairs, comes back with Etienne-Jules Marey: A Passion for the Trace by François Dagognet)

I was at an artists residency called the MacDowell Colony, and they have a library. I often would just go in there and browse around and this book was there, and I picked it up—this was a long time ago, years before I wrote this. As you can see, the images are stunning. I was really fascinated by them, even though I don’t think I really read the book, or maybe I just skimmed through it, but I remember photocopying a bunch of those images. I’d often return to them and I thought about them for a long time. They were kind of always with me, and I knew I wanted to do something with them at some point. It was probably back in the 90s when I discovered that book.

Wow, so this book has been gestating for a long time. When did the through-line between Marey’s work and digital tracking emerge?

There were a lot of stuttered starts to the project. I think I have always been interested in connecting the technologies that Marey was inventing and investigating with contemporary technologies, but technology changed a lot during the 20 years I was thinking about this, so there are some really early versions. I know that I started talking to a composer about writing a libretto, and I had brought up his inventions as a starting point, which, through a kind of butterfly effect, would lead to more contemporary technologies around surveillance, but that went nowhere. I dropped it for many years, with the idea that I wanted to pick it up again, and then finally I got to the point where I had to do it or not do it, and that’s what led to this.

I feel like, especially in the first essay, there are these moments of resonance with some familiar histories, like of Muybridge[1], that are more at the top of popular knowledge of the history of photography, and then there are more obscure pieces, like in the second essay with Walt Whitman’s lesser known engagements with phrenology. There’s an interface between all this history and the mundane moments of the present—like looking at nineteenth-century phrenologists’ charts and then looking at magazine covers at the newstand with brain science headlines on them. Could you talk about how you locate this deeper sense of time or these traces of past technologies in today?

I think I can try to answer that in two ways. One, my work is very interested in making those connections and thinking about how the past is always speaking to the present, how the present is always interpreting the past, or how the past only exists in the present. I’m really interested in how we use history and create history and how history has formed networks with the contemporary moment. And at least my experience in learning history was that it was kind of separate—it was this thing with a box around it. You learn the facts of it and then it just kind of exists autonomously, rather than thinking of it as essentially linked. Not that it predicts the future, but if we don’t acknowledge those linkages then we don’t have to be responsible for things that happen in the present.

Then, also, all of my writing is very process-based, and I’m always trying to acknowledge the process of making it. The Whitman piece that you mentioned, the phrenology poem, starts with Whitman because in an earlier book called The Network, I wrote this piece about Wall Street and Manhattan, and in my research for that I came across this anecdote about Whitman getting his head examined by phrenologists. I was so startled by that, and the fact that phrenologists were the publishers of the second edition of Leaves of Grass, and I decided to think about that a little more. If you look at those phrenology books, similarly, it was just another instance of nineteenth-century visual culture where I was like, look at that, these images are crazy! And wanting to work with them. And then it turned into this other investigation. I feel like for every piece there are kernels of it in previous pieces. They’re just ongoing fascinations and investigations, and they’re really all probably part of the same project, because you can’t really get away from your obsessions. You just keep re-working them, refiguring them, trying to understand them.

I was struck by the way there are these different maps, both of the mind and of this speculative landscape, and so much permeability between these concepts in the whole book. I was thinking about the idea of tracing movement versus tracking movement as I read it—specifically, in the way you use brackets to isolate language, almost as a tracking device in the text, miming the tracking that’s happening to the characters in a sense. What was your thought process in using the brackets?

I love that reading, I think it’s great. For me it’s one of those things that I give to the reader to work with. One thing that has meant a lot to me, that I learned from Paula Vogel at Brown, was Bertolt Brecht’s attitude towards the audience, that he wanted the audience to be engaged but also critically aware, critically distanced. He never wanted the audience to lose a sense of itself, so you could have a good time and enjoy a story or a song, but every once in a while, the house lights would come on, and someone would walk down the aisle with a sign saying “this is a play,” something that would make you meta-reflect on your position as a participant in the experience. I think about the brackets that way. There is this kind of dynamic where you have the two sides—the essay and the fiction—and I try to incorporate these moments that pop you out of that rhythm. The brackets are one of them, the other one is the bird kind of flying through at the end of each essay-paragraph, just trying to make it not so lulling, the patterning, so that you’re always thinking what is this? There are these moments that make you hyper-aware of how you’re making meaning.

There’s a line in here that’s like the ground is shifting beneath the characters’ feet, and I feel like that’s the effect.

The bird is like a refrain that the text keeps coming back to. I feel like each of these essays has a refrain—it seems very theatrical to me, almost like a chorus. I’m curious when it came up in your writing process. I also read in an earlier interview with you [with Charles Bernstein] where you talked about puppets and playwriting, and I was thinking about the bird as this kind of puppet that keeps coming back and ventriloquizing this growing ominousness of the data tracking.

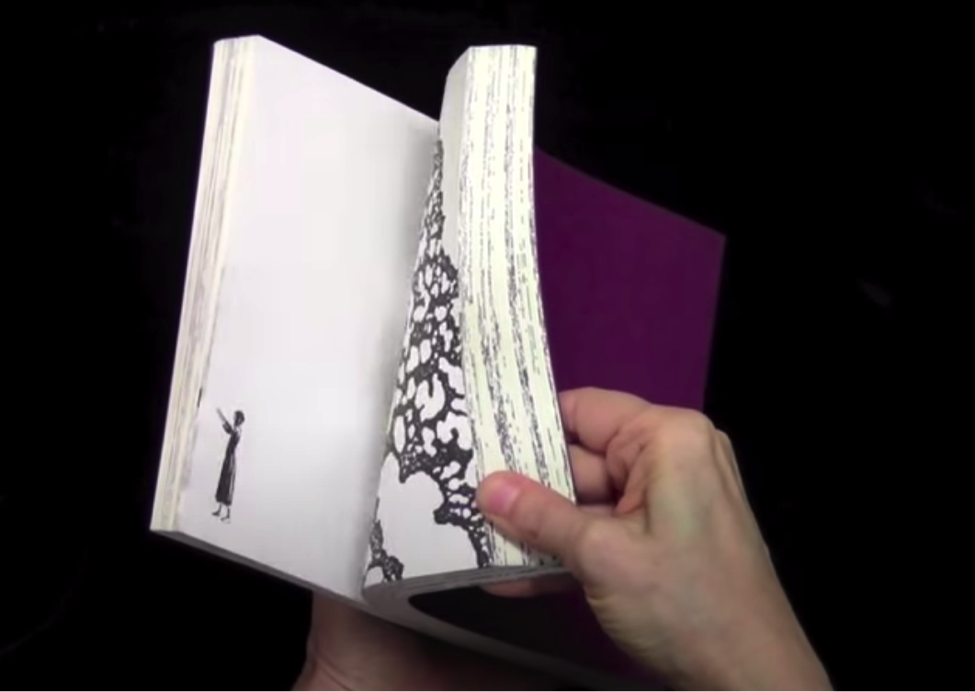

JO: At some moment in drafting the book, I realized I had two parts: essay, story, essay, story, and it felt wrong to just be going back and forth between those two things. It felt flat to me and I needed something to mess up this rhythm. That’s when I started to think about what that thing would be. The bird is all over Marey’s work, particularly in the chronophotography[2], in these images that were really important to me, but I was also thinking about all these movies that are about surveillance technologies. Basically the bird is the star in three movies—Blade Runner, Snake Eyes, and then Minority Report—so I pretty much just stole screenplay after screenplay. I was looking at the scenes with cameras and some kind of tracking devices being used, with discussions of “pre-crime” or all these data mining moments that are happening in these big budget films, and I put the bird in there to see what would happen. It’s definitely one of the things that people find more puzzling, especially if they don’t know the movies that I’m cribbing from. Blade Runner has a lot of very serious fans, so the lines from Blade Runner can be picked up pretty easily if you know that movie. Once you know that movies are being referenced in that way, then maybe you have a different relationship to it. But there are many people who have not seen Blade Runner and have no idea. There’s a footnote in the back where I refer to them as flipbook tags, or flipbook images at the end of each nonfiction paragraph.

One of the books that I was thinking about when I was thinking about flipbooks is a book I love by Janet Zweig, called Sheherezade. Sheherezade stays alive because she keeps telling stories within stories within stories, and Zweig’s book reproduces that action with an ingenious typographical concept. Meanwhile, there’s this lady in the corner of each page who keeps changing out of her dress as you turn the pages. With the flipbook being this early moving image, and how that speaks to the technologies that Marey was working on, I was thinking of these lines with the bird as kind of like that lady in the corner, like this other story that’s happening side by side with the story.

Yeah, that’s how it feels. This is so beautiful. I was struck by how in the fictional part of your piece, the ultimate damnation of these characters was incoherence.

Damnation, but also freedom in a way. The

problem with being coherent is that then you can be marketed to. They get in

trouble because their data profiles weren’t coherent, meaning that their data

couldn’t be used, couldn’t be bought and sold, and their desire to be off the

grid was a desire not to have to make sense of their lives in a market sense.

[1] Eadweard Muybridge’s sequence of photos, “Horse in Motion” (1878), captured the motion of a horse galloping, as an attempt to answer the question of whether the horse is ever fully airborne. Together with the work of Etienne-Jules Marey, these photographs were a significant event in photography’s development towards the moving image.

[2] Chronophotography is the photographic technique of capturing multiple phases of movement, a term coined by Etienne-Jules Marey.

Jena Osman’s books of poems include Motion Studies (Ugly Duckling Presse), Corporate Relations (Burning Deck), Public Figures (Wesleyan University Press), The Network (Fence Books, National Poetry Series selection), An Essay in Asterisks (Roof Books), and The Character (Beacon Press, winner of the 1998 Barnard New Women Poets Prize). Osman was a 2006 Pew Fellow in the Arts, and has received grants for her poetry from the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York Foundation for the Arts, The Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, the Howard Foundation, and the Fund for Poetry. She co-founded and co-edited the literary magazine Chain with Juliana Spahr from 1994-2005.

Paige Parsons is a writer from southern California. She lives in New York where she apprentices at Ugly Duckling Presse.

This interview is Part 1 of 2, the second of which will be published on 6/23/20.

This post may contain affiliate links.