[Ugly Duckling Presse; 2023]

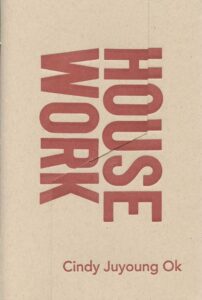

Cindy Juyoung Ok’s debut collection, House Work, is a delicate, hand-sewn chapbook, about the height and width of a paperback novel and slimmer than a magazine. The cover is made of natural paper-stock. The title, embossed sideways in red block letters, takes up nearly the whole cover. The book opens like a brown paper parcel: The back cover folds over the right margins to meet the front cover at the book’s center. The table of contents lists twenty-one poems with simple, mysterious titles.

Throughout House Work, Ok insists that writing changes what is written about. Form doesn’t merely shape content but creates it. This is a scary fact. Language threatens the freedom of things, making complexity seem fixed and turning loved ones into abstractions. Ok responds to this danger by treating language itself as material, the bricks rather than the building itself. By pulling language down to the level of earthly things, House Work seeks to set words—and the ideas, images, and people they describe—free to lead lives of their own.

Consider “The Five Room Dance,” the first poem in the collection. Ok writes: “as you stretch your books and I mine / the frozen language for olding hands.” Taken alone, the phrase “as you stretch your books and I mine” suggests two people engaged in the same disorientingly inconceivable domestic activity. But taken in conjunction with the following line, the phrase becomes “as you stretch your books and I mine the frozen language,” the possessive pronoun changes to a verb, and things get even weirder. Now, as the addressee does something to books, the subject does something to language. Words become different parts of speech from one line to the next; both meanings are present at once. Then there’s “olding”—is it an accented pronunciation of an English word? This is exactly how my French father pronounces the word “holding.” Or is it a synonym for the gerund “aging,” foregrounding the physicality of the body in time?

The answer is yes, yes. The last lines of this poem illustrate the body’s complicity with the dark forces of language. “I’m sorry we need to be bodies here, five doors in / a closed round, the words we cross a swarm / from which I am wrung. As I, wrong, form.” The first offense is having been born into a body at all, the second is the attempt to extract meaning from it. Wrong is now the past participle of wring. Throughout her work, Ok underscores the responsibility a writer has for their subjects, and the carefulness that such a responsibility demands. Here, that responsibility shows up in the speaker’s apology, the image of words as a swarm, the speaker’s sense of guilt for participating in all of this. Saying things changes them; writing them down threatens to make what moves stand still forever. Does the speaker really believe it’s wrong to create? The fact of the poem’s existence suggests that writing is still worth the risk.

Ok’s penchant for aphorism enforces her assertion that form shapes content. “A woman is a thing that absorbs,” we learn from the same poem’s speaker. The line is firm and mysterious, though I have the sense that Ok is talking about “women” as a socially constructed concept. Later, in the poem “Moss and Marigold,” Ok writes, “The country is / a construction, with each writing becomes more made.” Putting thoughts or descriptions into writing doesn’t simply catalog them. Aphorism is a good device for elaborating this argument; stating how the world seems makes it so. The poem continues: “I am making it here now, here, to you — to say my country / provides an illusion of synthesis.” The creation of concepts (“woman,” “country”) is ongoing. The real offense isn’t synthesizing complex ideas or people (because that’s impossible) but making them seem complete in your writing of them.

The poem “Park Street” is Ok at her best. “Everyone is envious of those more / alive than them and when we are not / aware of this we are directed by spite.” The statement forces me to pause, another example of the power of Ok’s use of aphorism. I hadn’t considered this before, but reading it here makes it true. People want to feel alive. Envy left to fester turns to spite. My pause is proof of Ok’s philosophy: The poem’s language works on the matter of my mind. Later in the same poem, Ok expresses a past desire to be witnessed and then, as in a Freudian dreamscape, the wish is fulfilled: The speaker slips from reverie into a changing room where’s she’s being watched by a man through the gauzy curtains. Before this moment, it doesn’t seem like this poem exists in a universe where men or changing rooms exist. At the same time, the revelation of these things isn’t jarring. I already trust the alchemy of Ok’s writing, how she can lend movement to something as fixed as an old desire.

As wishes come to life, typos change the meaning of a text. In “Table of Contexts,” Ok writes: “A machine I own mistook shootings / for students in a transcript, ushering / me to tilt canals toward titles and curate / hedges into pages.” Ok expresses the occasional uncanniness of autocorrect—when the algorithm creates meaning you didn’t intend to, and then compels you to believe it. Form isn’t stable, Ok tells us. Our containers aren’t safe. As the speaker puts it in “Tally of What Names” — “what maims the house maims me.”

It’s hard not to read the title as a reflection of Ok’s formal tools. Many of the poems in House Work take place in houses, but some don’t. Ok’s larger themes, like climate apocalypse or school shootings, inevitably enter our intimate spaces. For Ok, meaning isn’t something that exists prior to being written about. Meaning is constructed as we write. Close the book for a moment and look at the cover—because the title is printed sideways, the letters don’t immediately register as words. They look more like building blocks, a monolith in the center of the page.

“At the End,” the final poem in Ok’s collection, is calmly apocalyptic. The speaker offers a list of things for the reader to contemplate: “The fish whose stripes appear only on cooking through”; “the photo unglossed at the fold”; “the highway stop where toilet / paper is piled.” This is the kind of thinking that Ok champions. Thinking that honors liminal moments, bits of life that move too quickly to end up in a photo album. In another poem, Ok expresses the mobility of language another way: “Calendars flattened time forever, but we can keep / recruiting words newly, and asking for movement.” Her poems do just that.

Olivia Durif writes cultural criticism, personal essays, reported pieces, and book reviews. She lives in New Mexico.

This post may contain affiliate links.