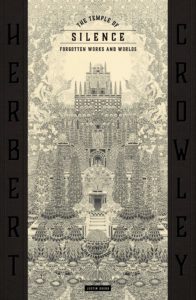

[Beehive Books; 2019]

Whimsy makes me uncomfortable. Maybe it’s just childhood memories of standing on the edge of some play rite, not understanding the rules of the game, only to realize the rules are being made up by the kid most animally magnetic. Maybe it’s that all the playful kids in horror movies are communing with some not-so-dead spirit. Maybe it’s Jim Carrey-induced originary trauma. Herbert Crowley, the subject and the artist behind the work collected in The Temple of Silence, has whimsy in abundance. But where that charming, seductive, and finally unsettling artistic persona might be, instead lies a hushed and gentle question mark.

Crowley is a curious figure, an oddity who at one point might have been something. Born in London in 1873, Crowley came to the United States in 1910 where he became a painter, sculptor, set designer, and comic strip cartoonist, working just a degree of separation from some of the most well-known modernist artists of the time. He had all the buzz and promise of fame, but ultimately never was famous. That’s not a judgment, but the reflection in history of the tensions between art as creative practice and art as marketable commodity that Crowley stands at the junction of. He is, after all, not well remembered, aside from a few scattered references, and it has taken the dedicated work of Justin Duerr, the author of the thorough biographical essay found here, who, with research assistance of Mandy Katz and Susi Wettstein, traveled actual continents and combed through literal ruins to recover what we know of the artist.

Henry Murger wrote of bohemian Parisian life in 1849 as a space “bordered on the North by hope, work and gaiety, on the South by necessity and courage; on the West and East by slander and the hospital.” Crowley lived in an adjunct of bohemia, a refugee of affluence — a singing career as a tenor scuttled by stage fright, a stint overseeing the loading of banana stalks on a Costa Rican plantation — he survived often supported by his family, his friends, his wife. He produced strange and remarkable work in drawing, set design, and sculpture, but ultimately was unable to market himself, whether that was because of an aversion to that aspect of art creation or because he was content to be less than sanctified. On the one side, he had his place in the famous 1913 Armory Show that brought the avant-garde to America, and on the other side he had his analysis under Carl Jung.

Of Crowley himself, one gets the impression that he felt impinged on by modern life — a thin complaint, perhaps, for someone from his background, but a relatable one. One gets the impression from the course of his life that Crowley didn’t love to make art so much as he loved the lifestyle of an artist. Residing in New York City and at an artists’ community upstate, designing sets for experimental local theaters, selling his work in profit-averse, mystic bookstores — all of this was a kind of grace for Crowley, a refuge from the modern world. “Artist” was the profession that would allow him to subsist in the milieu of New York bohemia, amongst the feminists, the literati, the anarchists, the actors, and other would-be visionaries, people whose most important trait was to have ideas worth talking about. So he became an artist.

At the center of the work collected here is the newspaper strip The Wiggle Much whose thirteen weekly installments ran from March to June of 1910 in the New York Herald. The strip is one of the early and pioneering newspapers comics, standing symbolically and in a literal sense beside the legendary work of Winsor McCay, whose gorgeous, full-page Little Nemo in Slumberland was also published in the Herald from 1905 until 1911. Crowley’s comic centers on the titular “Wigglemuch,” a bizarre and enchanting animal lost in a singular fantasia.

The world of Crowley’s comic, Duerr notes, is modeled on the flat dimensionality of toy, or paper, theater. Arising in the 18th century, toy theaters were mass-marketed sets of popular plays with cut-out characters and abbreviated speeches, so that viewers could buy and reenact their favorite scenes at home. Robert Louis Stevenson, a fan of the medium, wrote lovingly of the shop that sold them in his boyhood: “every sheet we fingered was another lightning glance into obscure, delicious story; it was like wallowing in the raw-stuff of story-books.” Crowley takes on a similar character of play and immersion, investing this flat world with appropriately blocky wooden-bottle townsfolk and tinsel knights. But against these static, clumsy figures Crowley has set the Wigglemuch.

Squishy, white and smooth, mostly torso, egg-shaped with two legs, no arms, but big expressive eyes and mouth, the Wigglemuch can be seen most often upsetting the comportment of the other toys. Alongside the Wigglemuch’s canniness to make limb-strewn chaos of your ordered rows of knights, is its own peculiar pathos. Its sad eyes and down-turned mouth show any child proof of a creature taken from its comfort to be used and abused in the schemes of others. He is at one unhappy point bedecked in armor and ridden into war — a fatal, yes fatal, mistake for his rider. It is some seven strips before the Wigglemuch is even seen to smile. A few episodes later we are made to realize that, though smiling, the Wiggle Much has no “light” in its eye, rendering its smile an unsettlingly vacant one.

One has to regard the Wigglemuch as expressing Crowley’s sense of not being at home in modern life, embodying the emotional responses of a sensitive person who struggled with depression and who felt keenly, it appears, the force of others’ opinions. In accompaniment of an incredibly detailed ink drawing of an immense garden overflowing with serpents and pests, Crowley writes, “Winding, like the snake, through all the finished and orderly tiers of flowers, in and out of view, permeating through the sheer horror of its presence,” Slander, also the title of the piece, “is seen and felt as the whole center of things until we lose sight of the beauty we have dwelt amongst through the insidiousness of the influence.” Once viewing art as a useful tool in the struggle of good against evil that shaped his mystical outlook on life, Crowley eventually gave up the practice, destroying much of his work in the last years of his life.

The Temple of Silence demonstrates the almost obsessive care for its subject matter that is characteristic of everything that Beehive Books puts out. Designer Maëlle Doliveux and editor Josh O’Neill in both their archival recovery projects and their new visions put across a tactile love of paper itself. Stevenson could find a suitable comparison for the paper theaters of his childhood only in dreams. This book is an adult’s version of that feeling of the bizarre unconscious that punctuates waking life. You are channeling Stevenson as you lift back the cover and turn the thick stock in your fingers. For this to be the end of Crowley’s work when the raw stuff of children’s play so often reverts back to just so much newspaper pulp, or some sodden, exposed sketchwork left in an attic — makes chaos of all the funny divisions of remembered and forgotten, high art and low, pop and avant-garde.

Frank Zappa, a marketable weirdo many decades after Crowley, gave consumers the dread direct address, Freak Out! Crowley, a gentler, more vulnerable man, asks “Wiggle much?” Probably not as much as I should.

M. Delmonico Connolly is a graduate student at the State University of New York at Buffalo. He writes and revises sentences about race and pop after the Civil Rights movement and is the author of the forthcoming chapbook, Ronnie Spector in Rock Gomorrah at Gold Line Press.

This post may contain affiliate links.