In 2018, Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina became the first graphic novel to be nominated for the Man Booker Prize. You always have to be a little careful when you claim that a graphic novelist achieves something prose novelists or filmmakers have not. With that said, I thought Drnaso did something with his blocked-out panels, deliberate pacing, muted colors, and subtle movements that I had yet to see in other media. Sabrina is a searing, slow-burn depiction of violence, disconnection, and loneliness in the Internet era. You experience his characters’ alienation, but you are not yourself alienated from his characters. In other words, he helps you feel a connection his heroes and heroines are denied. As such, there is a small glimmer of hope in his bleak narratives.

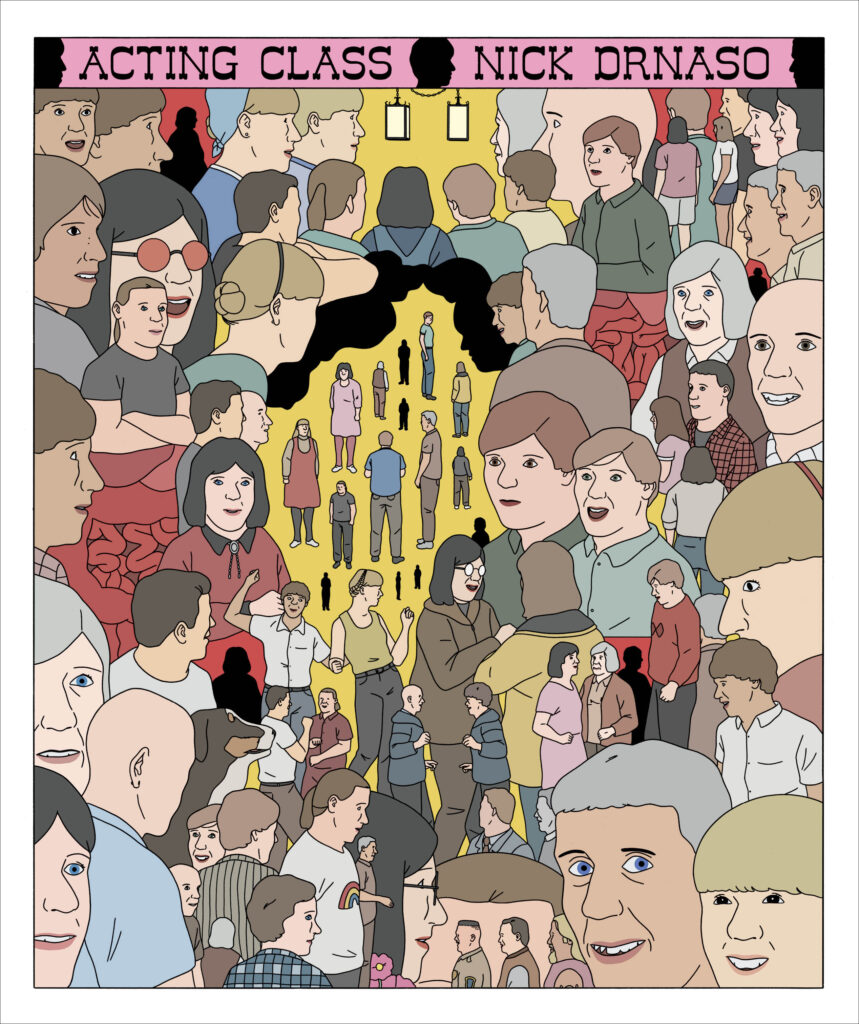

Drnaso’s latest book, Acting Class, is stranger and more ambitious, a story that moves carefully between the real and the surreal. It’s less about the technological hellscape we have created for ourselves, than more eternal themes, of what it means to live at the bottom of a caste system which prizes good looks, charisma, and an in-born sense of self-worth. We talked about it over the phone, while he walked around his neighborhood in a Chicago suburb.

The following is pared down from a one-hour conversation.

Paul Morton: Do you see yourself in a tradition of prose novelists? Will Eisner lamented that his work would only be seen in the comics section and not the fiction section, alongside Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, and Philip Roth.

Nick Drnaso: It was definitely graphic novelists and cartoonists for the first several years. I guess I’ve kind of pulled back a little bit. It’s become my day job. It’s what I do all day. So at the end of the day, I’m more eager to pick up prose or non-fiction.

With that Eisner quote, maybe the older generations have a little bit more hang-ups about those things, like where they [themselves] fit. Luckily, I don’t have any kind of chip on my shoulder. . . I certainly don’t think about it while I’m working on a book. Those thoughts just recede and are replaced by practical things.

Your characters feel very full. They don’t feel like caricature. The details are limited but very precise. When you’re drawing, [do you ever] say, “This looks too much like a caricature. I have to do more to make sure it’s more three-dimensional”?

I just do my best and I don’t claim to be a naturally gifted artist. It is a bit of a struggle as I’m working through a book and just trying to refine expression and tone and character design. There’s a lot of penciling and erasing and revising. As a result, it all comes out, as you see, very stiff, and kind of restrictive. I beat my head against the wall, sometimes, thinking about those things. But that’s just the way that I work.

Could you give me an example of a character that you were trying to get right, over and over again, one you were really struggling with?

At the beginning, the question of what the teacher was going to look like was something I went back and forth on. I made a bunch of paintings on glass, which was something I was doing at the time, just trying to figure [it] out.

There were earlier iterations where he was more wild-haired and wild-eyed. There was one painting I did where he was more an Ernest Borgnine-type, like a big boisterous man.

It’s called Acting Class. I’ve heard a lot of graphic novelists describe their work as a form of acting. I don’t know if you saw what you were doing as acting.

Yeah. You’re either thinking of your own face or faces of people you see every day as you try to approximate what you’re going for.

Did you take any acting classes for this?

No, definitely not. I had considered it, if I could put myself through it. But I’m just much too reserved. I’m the opposite of a performer. I’m very much the hideaway kind of artist.

Did you sit in on any classes, just to see how they work?

No. I kind of thought that would be too much of an imposition. I looked it up and saw that there were many—obviously many—acting classes around Chicago. Once I started writing, I was pulling a lot from going to art school and being in a lot of art classes, and thinking about that kind of classroom group setting.

In the classroom group setting there’s always the question of the ego. You want to be the best because you know how competitive it is out there, but at the same time you want to support everyone else. I saw a little bit of that in here. I don’t know if that was your experience in art school.

I definitely felt that tension. Competition is the best way of putting it. I recognized that especially in high school and maybe a little more in art school. But by that point I could just get invested in what I was doing and not get so interested in what someone else was doing, except by being excited by someone making something.

I remember that feeling more in public school and high school. I was just one of those students who was just crushed under the pressure of that. I couldn’t cope at all with that group dynamic.

And I was horrified and wrecked by anxiety anytime there was a public [presentation]. It got to the point at the end of high school where when the teacher had to announce a group presentation, I would have to pull them aside and say I can’t make speeches. That was a big hindrance for a long time. So again, I think that there was [an] appeal of working on an acting class from the safety of my home and just working with myself on paper.

You are in a tradition with Daniel Clowes and Chris Ware . . . there are a lot of fat bodies in your work, a lot of imperfect bodies. There are a lot of people who are very uncomfortable with their fatness, or their various imperfections, or their hair or whatever. You seem to want to lend them dignity that they don’t seem to want to give themselves.

I think that rings true and I would agree with that assessment. But I guess the question of depicting people has always been a struggle. I think that is why I just tended to make all the characters look the same, [at least] the faces.

You said you had the acting teacher as a more wild-haired figure. You have him as this conservatively crew-cut, gentle presence at the beginning. You know something is off in his personality. I don’t know if that reminded you of any teachers you had had.

As we’re talking, it’s occurring to me that the interest in an acting class and that kind of dynamic and just the world of being an actor and having a director—there’s just an enormous amount of trust that has to be established there. And I think that was kind of essential.

I tried to write that early, that it’s plausible, that he seems trustworthy on the outside. And maybe there’s the hint of strangeness. But then acting is a very strange thing when you get down to it, and trusting people—especially when you’re acting out something that’s putting people in a compromising position.

And obviously we’re seeing in stories that come out all the time [that] there’s a lot of room to betray that trust.

There are times when I interview graphic novelists and I can’t connect the person I’m talking to to the work they create. I’m not seeing you in person, and I don’t know your facial expressions, but there is a pacing to the way you talk that is very similar to the pacing in your graphic novels.

Oh, that’s interesting. I bear some resemblance to the wan, dour faces that I’m drawing. So you can imagine that.

There is a rhythm to the way you talk that doesn’t seem that far off from what I see on the page.

I think it is kind of a distillation of everything that you absorb. Down to what music you happen to be listening to that day or what your current obsession is, or anxious cyclical thought. I consider that a high compliment, because I’ve experienced that too with cartoonists where I might know their work for years and then meet them and I feel like I can tag personalities before I even meet them. And you’re right in some cases. You are thrown a curveball. But for the most part with comics, for better or worse, you can’t really hide from who you are. You’re spending so much time working on these things that you can’t keep up a persona for that long.

When you walk around your neighborhood do you feel the sense of isolation I sense in your books?

I’m not resigned to it. I guess I’m an isolated person. I’m trying not to romanticize that, because those themes come up a lot in conversations. Maybe when I was younger, I romanticized things like that, but now I’m trying to figure out how to shed that and feel more kinship with people.

I’m not misanthropic really, or cynical about people in general. When I go out I can like talking to people and can be pretty comfortable socially. But my lifestyle and the constraints and the pressure I put on myself and my work has put me in this little confined space of my own making, where I’m like, “If I have to step out of the house and I see my neighbors are watering their garden I’ll just slip back inside.” Just to avoid the little pleasant exchange which is supposed to be part of being a human being.

I don’t think there’s a part of you that hates any of your characters or could find a character that you hate. Am I getting that right?

Yeah, I don’t relish having a punching bag type of character. That’s true.

Do you love all of them?

I think the characters in the first two books were kind of mannequins. The emotions and the inner lives felt more wooden—to me at least.

[I]t always sounds cheesy when you talk about your relationship to your own fictional characters. . . . Over the course of working on this full time, and over the course of the pandemic, I did feel that something deeper and deeper was being established, whether or not that translates to a reader. . . . It was to the point where when I’d be flipping through old catalogues, old JC Penny catalogues . . . I was thinking, “Oh that would be a dress that Beth would wear.”

Do you miss your characters now that they’re gone?

Those things do actually happen. I think there is a sadness that sets in when a book is finished, and when it comes back from the printer. The life and the excitement doesn’t really continue.

I’m not a musician, at all, but I have to imagine that if you put out an album there’s a certain life that continues when you get to go out and play these songs again. But with what I do, with the book, it ends kind of definitively. And the feedback and the reception doesn’t feel like a continuation of the process. And also the stress of what’s going to come next immediately sets in and that just takes over my thought process.

Do you still dream about the characters?

No. I just let it go. Something snaps and [there’s] a cloud of optimism that I try to ride. I have to call it ”false confidence” because I have to delude myself into thinking [what I’m working on] matters.

And then it’s best not to think about it for a long time and kind of look forward. At least for me, it’s a healthy way to keep working.

Paul Morton writes about comics and animation. You can contact him at [email protected].

This post may contain affiliate links.