[Silver Sprocket Press; 2022]

On May 9th, 2022, an old and familiar name returned to presidential rule in the Philippines. Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., son of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos, was given not only the reins of the country’s future in his hands, but also those of its past. Throughout his campaign, Marcos Jr.’s strategy was to refurbish memories of life under the rule of his father. Per historians, journalists, activists, and survivors, it was this all-out war on the misinformation front—recasting the brutal legacies of the martial law era in a new light—that has led to this dark recapitulation of Marcos family rule.

What is the cost of remembering the past? In recalling history against its enforced, scripted versions? For many, regimes of misremembrance can feel like opening a closet full of skeletons, only to find beautiful shoes.

The comics medium has always been at the heart of debates around fictionality and truth. Art Spiegelman famously petitioned the New York Times to move Maus, his seminal graphic series about the Holocaust, from the category of “fiction” to “nonfiction” on its bestseller lists. Currently, the nonfiction graphic novel combines extensive, often decades-long personal and historical research with comics artistry and has become a thoughtful and compelling medium for telling history.

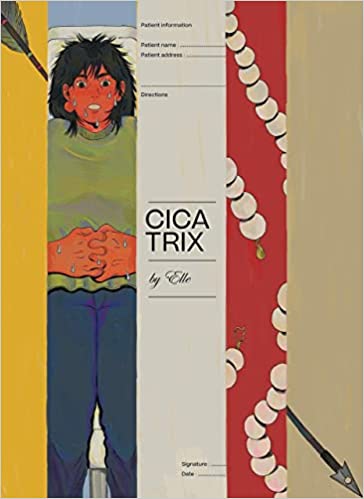

An example of the genre, Cicatrix, newly released from Silver Sprocket Press, is a comic by Philippines-based artist and writer Elle. The book deals with the traumatic and bodily internalization of state power and seeks to clinically, historically, and emotionally parse through the skeletons in the author’s own familial closet. The narrator’s medical journey to know the cause of a mysterious skin growth becomes, too, a diagnostic for political harms perpetuated by members of their family, who once enjoyed close relations to the old Marcos leadership. Elle’s graphic depiction of the horrific excesses (and abscesses) of political rule constellates a variety of contradictions, both visual and narrative, around coming-of-age in a never-quite-post-Marcos world.

The book’s narrator is a young Filipino person who has developed a kind of “karmic hypochondria,” and believes that they are being medically punished for the wrongdoings of their family. The story begins when they seek medical attention for a reddened bump under their ear and soon realize that their doctor previously served as Imelda Marcos’s personal ENT doctor, which promptly upsets their stomach. As family ties to the Marcos are gradually revealed—a grandfather in the Marcos administration, an uncle in the CIA, another uncle in ICE—so do the maladies abound: inflamed cuticles, nervous tics, splotchy skin.

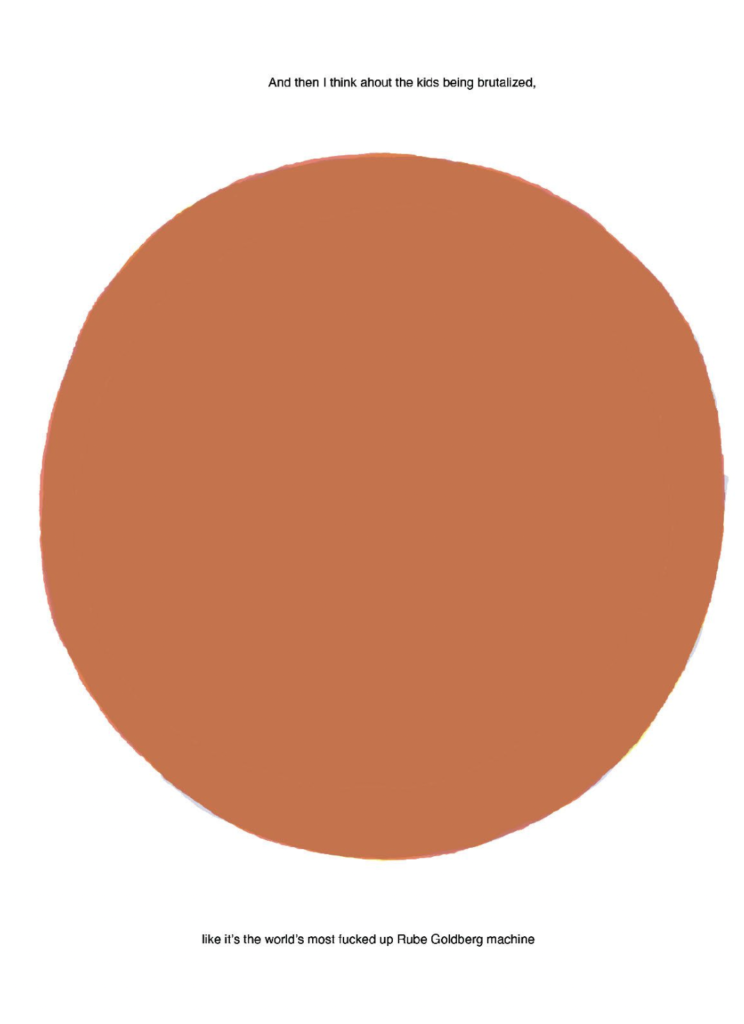

The stains of both flesh and conscience coalesce in the visual motif of the skin bump, which moves not only visually in placement on their body but is further abstracted into the red circles that multiply and grow across the pages of Elle’s family line—a marked history. The circles—which begin as dots and grow to engulf whole scenes of familial past—show the process by which the narrator’s eye is reconstituted by this knowledge. Whether it is their cousins’ penchant for country music while their father works for ICE in the Mexico-San Diego border, or the supposedly CIA-funded RISD portfolio that their cousin shows them, there is no detail too finite, no familial quirk too particular, to be understood apart from its closeness with the Marcoses.

One begins to realize the confessional nature of this act of storytelling through the enumeration of the family’s hand in the state violence, filed under section titles like “The sins of the father” and “shall be visited upon the children.” Cicatrix’s own relationship to fiction and history is a key into its ideas about narrative and truth-telling. Important parallels are drawn between the narrator’s fears of being examined by Imelda Marcos’s doctor and the violating biosurveillance of the state. In a sequence of panels where the narrator is being physically examined, they express their fears: “I was paranoid that when they’d listen to my heartbeat, or look down my throat, or take vials of my blood . . . They’d blow it up on a screen, crunch the numbers. And then everything I feel would be typed out plainly, objectively with no more need for interpretation. With no more space to grow. Combed over until everything is flat.” Here, the narrator’s imperative to discover the truth of their past is opposed by their will to remain opaque to the government and to the datafication of their identity. This act of disclosing the dark history of their family also becomes a project of interpretation, of navigating a body and a history without surrendering them to state authority. The comic shows that it is difficult for the body to keep score and the mind to keep its secrets; that the processing and translating of intergenerational history comes at the cost of the physical and psychical life of the person.

Anti-authoritarian themes are consistent throughout the work. The comic opens with a 1000-word historical essay, which focuses on the capitalist underpinnings of the Philippines’ martial law rule and the US’s complicity at every juncture of the Marcos reign, continuing up to the present day. This articulate and charged historical preface creates the backdrop for Elle’s individual narrative of political struggle, and allows for dilations between state and self, politics, and emotions, as well as body and mind, to proliferate throughout the text. The essay ends on the case of Jennifer Laude, a trans woman and sex worker whose murder by a US Marine (who was later granted absolute pardon) is, per Elle, an emblematic reprisal of “the story of the Philippines, one that seems to follow the same tune no matter the decade, and the reality of imperialism, militarization, and reactionism we continue to struggle against.”

A panel of protests surrounding the Jennifer Laude case is what ends the growing red spheres of the comic, indicating a radical shift from Elle’s mounting guilt to direct political action. The redness finds new shape in the flames of the protestors’ torches and in the signs of the organizations for victims and relatives of extrajudicial killings. This aesthetic and analytical move by Elle situates the blood-red guilt of the narrator, who is implicated in the crimes of the ruling class, against the great risks of on-the-ground protest. This panel does critical work in moving the text beyond just an inventory of crimes by highlighting the important and oft-erased movements of struggle in national histories.

Cicatrix falls somewhere between the contemporary graphic genres of autobiographically voiced world history, such as Marjane Satrapi’s 2000 Persepolis and Thi Bui’s 2017 The Best We Could Do, and the psychosocial deformations of the body in horror, such as in Charles Burns’s 2005 Black Hole. If Elle’s comic gains its appeal to humanitarian realism through the genre conventions of the former—which has an aim to humanize politically displaced peoples—then it creates space for narrative’s violent and disfiguring ends in the latter. It is a comic, like these predecessors, that addresses narrative’s use as a tool, for and against human life. Just as the grief and guilt of the narrator’s past visit upon their flesh, so did the Marcos regime rage war against the body in the form of the tens of thousands who were tortured under detention. Cicatrix reinscribes the brutality of the pen and the culpability of narrative into its own powerful, and beautiful, interpretation of history.

Ann Ho is a PhD Candidate in English at the University of Pennsylvania and studies urban transport and global media. She makes and reads a lot of comics.

This post may contain affiliate links.