[City Lights Books; 2019]

[City Lights Books; 2019]

Henceforth, we know that we are foreigners to ourselves, and it is with the help of that sole support that we can attempt to live with others.

— Kristeva, Strangers to Ourselves

Brandon Shimoda made a book of prose and it is astonishing. Among other things, The Grave on the Wall performs a memorial in linked essays to the author’s grandfather Midori Shimoda while scraping away at the grounds for such a memorial, for any memorial. The Grave proceeds steadily. The first essay begins: “My grandfather had one memory of his childhood in Hiroshima: washing the feet of his grandfather’s corpse.” Persistent sentences, urgent and largely unadorned, shuttle between memory, travel, dreams, and histories both researched and received. While the essays wander wildly, in many ways they consider and unfold and attend to nothing more than this first sentence. How exquisitely and at what cost do memory, body, family, and state endlessly interplay.

It is not difficult to find Brandon’s writing. He put out six books of poetry in ten years. By my count, over the last three years no less than twenty-five different publications have published his work. And still, encountering The Grave on the Wall, the intimacy and openness of the prose, the thrilling surfeit of so many sentences in one place, it feels like something different altogether. While covering similar terrain of his published work to date, The Grave offers a new capaciousness to feel with and think through, an invitation and injunction not to break off one’s gaze. There is something weird about Brandon’s writing. His poetry often revels in a syntax that twins jokiness and terror, capturing both the alienation of an inside joke and the invitation of a veiled threat. From one of several poems titled “The Grave on the Wall” from his 2011 collection Portuguese:

Where were you when you were with

The gathering of good friends coming down

Looking half good, cooking good fortune

Friends’ hair coming rain, friends’ rain coming asses

Twisting the sun, inverting the sun

So too are the essays weird, but the sentences are starker, how much has been pared away. They operate more through humility, through reflection and finding, through marking injustice and violence, and through an erotics of recursively looking for and looking after.

We walked into the tide toward the torii gate. Seaweed was bright green on the sand. When the tide is high, the gate floats above water. The tide was low, going out.

We asked everyone we met in Hiroshima: Are you going to the memorial?

And everyone we met answered: No.

Narrative is at risk here from contesting claims. We find the story riddled with other voices: FBI files, emails, poetry, film, transcribed conversations, and oral histories. Identity is shifty, multiple. Within three pages Midori is evoked by an FBI file excerpt (“Subject stated he thinks Japan is ‘Hell’”), a number possibly associated with his internment (“1128762”), a childhood memory, and biographical information from museum signage for an exhibit. Long lost great grandmothers are unremembered, misremembered, recovered. The narrator himself is an astute poet and cultural critic, is an attentive and compulsive genealogist, is an awkward ten year old fumbling with race. His sister and him at their great-grandmother’s nursing home become “two preposterous children and their plundering, idiotic gazes.” One essay transcribes a call to someone who may or may not be Midori’s first wife and with whom Brandon must assume a character in order to continue speaking. Meanwhile kitsune, trickster/guardian fox of Japanese folklore, shows up throughout, in a reference to Kurosawa’s Dreams or observed on a high desert cliff, blessing us, putting us in danger. Where are we headed is a real question the way the essays swerve and open out, and the result is often breathtaking.

The essays are dark in the sense that history is dark, that empire is dark. Dark in that it shines unyielding light on things we know but may not have sat with staring. We get the precise mechanisms and dislocations of Japanese internment. We get the specific effects on a body, on a national identity, of targeting civilians with no less than the most powerful weapons on Earth. The book effects a darkening in the way that Brandon’s family moves from brightly lit, suburban nuclear family into something less clear by being subject to so much attention. Gaps in memory show up. Genealogy adds new ancestors who had been forgotten or effaced. Where family names compound place names further compounded by uncovered details, the names, for example, of transpacific steamers, research turns up proper nouns that begin to pile and threaten to occlude: “What family was I feeling?” There is the darkness of what cannot be known or recovered at the edge of memory, both in terms of collective forgetting and literally through the progress of his grandfather’s Alzheimer’s. A dissolving back into impenetrability: “a room without walls, the wind sowing emptiness before it.”

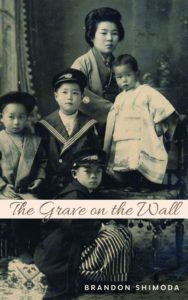

One of the preoccupations of these essays is attention to the corporal. There are a lot of bodies and their parts, and the pleasure is in the way these bodies refuse to resolve. There is a macabre thrill, a Western viewer encountering the beautifully composed violence in Japanese woodblock prints and its graphic after life in Japanese cinema then Hollywood horror, maybe even hints of the visual language of metal bands. It is also mere, lucid description. Given state-sponsored violence, given natural and anthropogenic disaster, given old age, the bodies pile, the body comes apart. Bodies show up in the incredible reprinted photographs that pepper the text, figures who look into the lens, from archives and family albums, from his grandfather’s career as a professional photographer, from internment camp staff. They function as the burning mirror from a dream of Midori’s. Both object and method of inquiry, they work easily into Brandon’s highly optic prose. This one is presented without comment, this one is subject to a meticulous, incisive close reading. This one thrown in from off a digital camera. This one turned dream-poem-talisman he lived with under his pillow for a year. The delight is in such rich specificity, how human a face makes us. And yet throughout the essays we get an alternative history, of picture brides and seditious photographers and a grandfather who will not recognize himself, where representation itself is effacement. Like so much of the book, the effect is oneiric, at points delirious.

***

It was late. Maybe the bar had closed, maybe we were in someone’s half-lit living room, the few of us still up. Could be the night we drove to a bar in the next town because the bar was in a poem. Brandon was telling a story very slowly from when he was young. His father had called his sister and him into their darkened dining room. The room was not large. “You could fit a sixty foot beam in this room, a hundred foot,” his father said to them. “If you wanted, you could get the entire beam in here. Think about it.” That was all.

Do I remember it right? A quiet, odd exhortation to achieve or innovate or otherwise refuse or neglect constraints, even intractable physical ones. It is about the perfect details that clarify a family dynamic, about the details that get at what is ineffable and unknowable in that dynamic. It is about an unreasonable timber beam floating, dislocating everything by wordless, witnessing presence. What is this story? Why is it that we will never be able to forget it? Brandon’s voice is different from a decade ago when we both lived in Montana. It is plainer in certain respects, more urgent. It is gently commanding, inviting but also resisting, and I find myself rapt as I used to find myself rapt whenever Brandon told a story. The Grave among other things reads as a feat to me, as if something truly massive were fit into two hundred pages, without compromise or shortcut or disassembly or surgery. As if an impossible and entire monolith were fit between the covers. I imagine a thoughtfully planed beam of hardwood from a temple otherwise destroyed. Both locating and dislocating us, the marvel of its accomplishment hovers ominous and irreducible, a whole and deep act or care.

Nabil Kashyap is author of the essay collection The Obvious Earth (Carville Annex Press). He is a librarian at Swarthmore College and lives in Philadelphia.

This post may contain affiliate links.