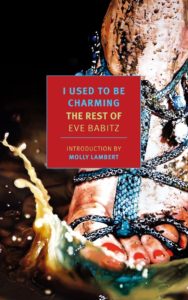

[New York Review Books; 2019]

Recently, I jokingly posted on social media that I was too much of an airhead to be a Susan Sontag completist, but that I certainly considered myself an Eve Babitz one. This was before I finished her new collection of writing, I Used To Be Charming. Though the fact remains true: I have digested everything that I can find — without too much difficulty, at least — written by Eve Babitz: Eve’s Hollywood, Slow Days, Fast Company, Sex and Rage, L.A. Woman, Black Swans, and Two by Two: Tango, Two-step, and the L.A. Night. Nearly all of these have been reissued in the past several years, marking what many have called a Babitz revival; people love reading Babitz all of a sudden. Do not get me wrong, though, because I certainly still consider myself a fan, and previously would have even said that I was a Babitz die-hard. But my feelings for this collection are knotty, to say the least.

For the first time ever, we have an accessible collection of Babitz’s other writing, which had previously been near-impossible to track down — the profiles and essays that she published from the 70s and into the early 90s, and which were run in Esquire, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Conde Nast Traveler, Playboy, Rolling Stone, and also defunct publications like Wet: The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing and Francis Ford Coppola’s City Magazine. The most notable pieces in the text are the one in which Babitz observes the production of The Godfather Part II, a piece that tells the story behind the famous image of Babitz playing chess in the nude with Marcel Duchamp, and the essay the collection is titled after, in which Babitz intimately writes of surviving a burn that ravished her lower body, and which turned her into the recluse that she continues to be today. This isn’t Babitz’s best writing, but because it includes previously lost essays, this text is essential to Babitz dogmatists.

In the titular essay, which was written for this collection, Babitz writes of the incident in which she burned the bottom half of her body, and then details her months of recovery. Oddly enough, this piece, her most recent, is also probably the best piece in the collection. She writes using her famous charm and wit and sharp observational skills. As far as the story goes, Babitz was attempting to light a cigar (which, per Babitz, Demi Moore made appealing when she graced the cover of Cigar Aficionado in 1996) while driving, when the match fell and her gauzy skirt caught on fire:

Here’s what you would have witnessed if you happened to be standing outside the Raymond restaurant in Pasadena on April 13, 1997: A ‘68 VW Bug comes to a stop, a woman flies out, skirt aflame. She drops to the ground by the side of the road, rolls on the grass, setting the grass along the side of the road on fire, and then against the green bushes, setting those on fire too. “Oh no, oh no!” is all she can manage. That woman was me.

In fact, about thirty feet away, a poor Sunday-brunch couple getting out of their car did see the whole thing. They stopped in their tracks and watched as my skirt burned off, as my skin turned to char. “Can we do anything to help — ?”

“Oh no.”

Babitz writes of the incident with grace and good humor. But it’s almost as if Babitz is in denial, as she refuses to acknowledge how greatly it affected her life (it led to decades of isolation, for example). She does not want to be a Debbie Downer so, instead, we are given a scene of pure slapstick — which gives the piece an odd aftertaste.

Babitz writes of how her sheepskin Uggs protected her lower legs from burns, and how her friends would be so so so angry if she died (“I imagined how pissed off my friends would be if they heard I actually died from trying to light a cigar.” And again: “My friends would kill me if I died.”). And when her cousin comes to visit her, Babitz writes: “When she first saw me after the surgery, I was bundled up like a burrito, my face and body swollen to three hundred pounds. We looked at each other and the word came at us at the same time: abattoir, the French word for slaughterhouse. All my life I had wanted to have a reason to use the word abattoir.” See, Babitz has not lost her caustic, self-deprecating, and observational humor. But does it still work? Or, rather, is it what we need?

In “I Was a Naked Pawn for Art,” Babitz writes of posing nude with Marcel Duchamp. The resulting photograph has since been reproduced and recirculated over the years for a variety of purposes, making the image the one piece of Babitz to have reached a larger audience. Which is to say, most likely more people have seen Babitz nude than have read her work. But the story isn’t that exciting: Julian Wasser, a photographer for Time, simply asked Babitz if she would do the shoot, and she said yes (though she agreed partly to get a rise out of Walter Hopps, the owner of the Ferus Gallery — in which she would be photographed — and Babitz’s married boyfriend).

Things move quite quickly after she agrees, and before we know it Babitz is being picked up to get photographed with Duchamp: “When Julian came to pick me up, I was wearing clothes of nunlike severity so nobody would have the slightest reason to believe I’d take them off: a gray pleated skirt down to my shins and an Ivy League blouse.”

At this point, Duchamp had retired from art to simply play chess (“or so he wanted the world to think”). And, from what Babitz shares, Duchamp took their chess playing seriously (“ . . . sitting naked in the museum, having to play chess with someone who hardly spoke English and was so polite he pretended that the reason he’d come was to play chess . . . ”). So while the image is iconic, the story itself can’t surpass the power the iconicity of the photograph has; the story is more of a history lesson learned, a mystery uncovered that many contemporary readers have often wondered about. The essay’s worth lies in its voice; it’s classic Babitz.

“All This and The Godfather Too,” the opening piece of I Used To Be Charming, similarly explores the pleasant mundanities of celebrity life — through Babitz’s sometimes meandering, often whimsically casual, and always cool and glamorous style. “My main feeling about him [Francis Ford Coppola], which gets stronger and stronger as time goes by, is simply abject belief in his greatness. I want to be on his side,” Babitz writes as she shadows Coppola and his team as he films The Godfather Part II on the heels of the release and reception of Coppola’s The Conversation. She casts Coppola in an endearing and respectful light — he is a gentle (“Francis strolled around throwing chocolate-covered almonds into everyone’s mouth.”) and brilliant artist (“Francis is strange about actors. He believes in them.”) with endearing idiosyncrasies (“Monday is when Francis doesn’t eat anything all day. It makes him anxious and bored.”), and proves to be a true artist as well, one that would rather do the work than deal with all the other hoopla of the industry. Babitz’s feelings for Coppola in a nutshell: “On Francis’s side are Righteousness and Truth, Pure Untainted Visions of Ancient Glory and Modern Goodness. On the other side are the Capitalist George Grosz Money Masturbators, amassing Power in secret vaults.”

There came a moment in reading this piece where I became aware of how rare such pieces are today. Babitz was given incredible access — she had all sorts of freedoms to roam the sets and socialize with everyone involved in a manner that is no longer the norm. Instead, profiles now are often given severe limitations by publicists, and are then highly filtered and edited down afterwards. But here, because of such freedom, Babitz makes it clear to the modern reader just how much everything has changed. Inadvertently, Babitz has shone a light on the shifts that have occurred during the period from when the piece was published to now. As I read, I expected her to write of sinister and inappropriate acts occurring off the screen and in the shadows, as I do when reading anything written about Hollywood nowadays. It gave me an icky foreboding sensation, one that gestures at the unacknowledged darker underbelly to the scene Babitz describes. This is a feeling I was unable to shake off throughout the entire collection. Babitz’s Hollywood is a utopia, which does not lend to pleasant reading. Instead, it highlights a prevailing blindness to what was occurring just a few feet away.

Again, I am happy such a collection exists, but I am torn because the pieces are alarmingly apolitical and, in 2019, sometimes appear tone-deaf. These pieces exist in a bubble, within a world not publicly plagued by varying issues of impropriety. The text fails to address the harsh truths that have surfaced regarding the very Hollywood Babitz so adores writing of. She is the essential Hollywood chronicler, and her pieces are too chaotically neutral: they fail to address the unsavory actions occurring just outside the frame.

We can ignore this fact, and simply acknowledge that they are dated and that this is a collection that is meant to just be a collection of previously lost writings, one that is not specifically meant to have any current social resonance. But then I consider other recent collections that have served a similar purpose, like Gary Indiana’s Vile Days. Indiana’s text, however, still reads as urgent, and not specifically outdated. Indiana’s columns in Vile Days are still politically reverent and socially relevant, while Babitz’s text is maddeningly and absolutely apolitical. But the clincher is that this isn’t new about Babitz — these would have been apolitical then, too.

What I mean to get at is that it is difficult to read non-fiction centered on Hollywood in the present — but it is more difficult to read about a Hollywood that hasn’t yet been lit aflame. I would rather read a cynical text about men going down than a cheerily blind one about men going up and up. For that reason, this collection lays cracks in my mythos of Babitz. Her writing is too saccharine for a moment in time that demands we be increasingly invested in the political.

There’s a sense of nostalgia that Babitz conjures that I have in the past found attractive. But my response this time around is a feeling of frustration — mainly, from naively wishing that someone had just blown the gasket way back then. Recently, I wrote about Natasha Stagg’s Sleeveless, which is not unlike this collection in the sense that both focus on celebrity culture and media in an urban context, and both writers share a similar cool wit. But Stagg does confront the icky power dynamics of media. Babitz does not. There’s a refusal there — or is Babitz actually so aloof? I suppose I was not surprised when I read in a recent piece written by Penelope Green for The New York Times that Babitz is apparently rather politically conservative. Green even makes a passing mention of her three MAGA hats (not just one).

Babitz has always been a bit indulgent, her writing that of a hedonist-cusp-nihilist — so unlike Sontag and Didion, her contemporaries then. But their writing, like Indiana’s, remains urgent, leaving me to again wonder: how do we engage with writers of the past who do not reflect our current politics? I suppose not many were writing about the infelicities occurring in Hollywood then. But is it not tone-deaf to release this now? Even while these were written thirty years ago, an introduction that confronts the changes that have occurred would have been welcome.

Babitz’s writing is about the mood she conjures: a bit amusing, shrewdly observational, glamorous, and, well, fast. Her writing isn’t about the stories she tells, though they help; her brush ups with celebrities, and drugs, are a nice tonic, but it really is about this mood. It’s the mood of a razor-edged, probably a bit stoned, bulldog that could take someone down, easy. It’s a shame that her purposes always lay elsewhere, in describing parties, boys, ennui. Imagine the political takedowns she could have penned instead. Ultimately, all I can do is hope that the next Babitz book, if there ever is one, reignites my earlier ardor.

Josh Vigil is a writer living in New York.

This post may contain affiliate links.