“October’s an iron pot full of small golden birds, boiling and singing like flames.”

In a fit of Halloween spirit, I went on an after-dark cemetery tour. We arrived, we looped along the stanchions with the rest of the line, we shared in the gentle pulse of anticipation. Even if we had not been on this cemetery tour before, even if we left no breadcrumbs, we knew the path it should take. An enthusiastic tour guide would lead us through the literal and figurative dark, stitching just enough narrative culled from this necropolis to light up something about its corresponding metropolis, in turn lighting up something about its denizens, us. That, plus the fact we are going to die.

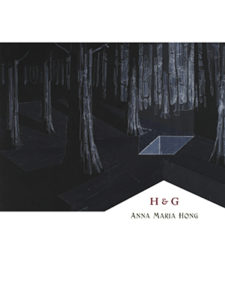

I was reminded of this particular after-dark tour while reading Anna Maria Hong’s H&G, a lovely and strange novella wrung from Grimm’s “Hansel and Gretel.” A short book (59 pp.), it is in turns gorgeous and coolly analytic, wild — almost goofy — and starkly sane. A speculative feminist excavation of Western mythos, though not concerned with antiquity per se, the novella calls up Luce Irigaray, Anne Carson, or even Vi Khi Nao. Hong proceeds through a series of approaches staged in short stabs of poetry, essay, flash fiction, obsessively combing the Enchanted Woods for clues: How should we position ourselves in relationship to H & G’s trial by candy? How do we enter in conversation with a dead story, with the dead, when the cemetery itself is now a high-fructose laden, second-rate attraction? When our tiny tour group was called to join our guide, instead of flashy ghostbuster jumpsuit or LED-studded skeleton or goth employee just dressed regular, we got Steve. Land’s End jacket and Flyers cap, he was dressed as a tour guide, he said. It got stranger.

“[A]nother sad fate to avoid,” that’s the tagline we expect from this kind of story. But rather than the grisly and/or mysterious endings of the landed gentry of a fancy cemetery, we got sideways stories about land acquisition, bit parts played by minor figures in complex legal and military dramas, anachronistically acquired remains for the purpose of (necro)celebrity draw. Amid the encyclopedia of loss that is a cemetery about to celebrate its bicentennial, we were denied the fairy tale and got instead the fine details and circumstances that form the ground of the tale. Steve did not make stuff up and what’s more, he knew his shit. Meanwhile we were sipping heavily-fortified hot toddy while somehow the other members of the tour, whom we did not know, were through no mechanism we could detect getting drunker, too. Every once in a while our path would intersect with a more performative tour guide and their group, snatches of a cohering ghost story, but we would be led away before the story could fully assemble, before we could be beguiled.

Anna Maria Hong probably owns zero jackets from Land’s End but can be just as eerily attentive, and after an analogous kind of rigor in her excavation of Grimm’s fairy tale, as tour guide Steve. Steve, turns out, was a practicing lawyer, allergic to the kind of invention that might reduce a story to its tale, to what might lead us through unscathed. Clearly what pulled him in night after night to this cemetery was not what drew the other, more excitable guides. What drew me in, page after page, was not the narrator’s Steve-like wry authority, nor a fairy tale’s Gothic excitability, nor even excitability’s refreshing absence. Instead, it was the cumulative effect. Rather than a polished ghost story necessarily told from the survivor’s vantage, H&G operates by way of a ragtag band of perspectives and narrative possibilities — Gretel’s but also those of Hansel, witch, father, stepmother — stumbling through the graveyard of Western psyche that is the terrain of an overtold folktale. Layer in the narrator’s own personal compulsion toward and revulsion from this particular tale, and behind that, the thin covenant of belief and a peeling away of the deep normative cultural dreaming that affords such a fairy tale persistence. “If the Believer stopped believing, would the world cease to exist?” Some on this tour are rapt. Some, on the verge of revolt.

At some point the group was inebriated, the unrest was vocal: “The women! Where are the women buried?” Question for any of Grimm’s tales, and as Hong meticulously unearths, particularly so for Hansel and Gretel. The book subjects the siblings to probing analysis, particularly Gretel’s psychology post-trauma, or as they say, happily ever after. The painful individuation of siblings: to have experienced events as one, but after to consider them separately. “The tragedy is that only one of us sees it that way.” How often the woman’s version is deemed suspect, under-articulated, needs work, or as Hong writes, “No one wants a woman who walks away from misery.” Sometimes, though, the guide comes under scrutiny and the tour itself is threatened: “The Mother’s tools may unmake the Father’s house.”

Plus, if this was supposed to be our necropolis, where were our progenitors? What if we know the story by heart, inculcated by an enchanted version of the Black Woods, but we look nothing like its protagonists? 85,000 plots and not one stone with a name like mine. “you are G. writing a novel about patricidal hatred, inherited misogyny, and looking for good kin. / you are G. as little Korean American Fraulein . . . ” It takes considerable and mostly unacknowledged imaginative effort to see ourselves in the fairy tale, for the tale to believe in us.

There were moments of silence. It was strangely meditative: phallic monuments in light stone at almost regular intervals against the city approximation of dark. We crested the hill and caught a glimpse of the river, the far bank’s unmoving trees. Cycling through genre, the book rests in experiment: tries on essay, diary, list, counterfactual, lyric, anaphora, memoir, appropriates Freud, Berryman, Bishop, reproduces an incident report from one Ranger Charming. Restless as it might be, Anna Maria Hong’s grounding in poetry shines through when needed: “Feather upon feather and everything compels this sugar; the hand swings wider.”

What H&G uncovers is that holding the tale together is not the inevitability of narrative arc or even subterranean mythic archetypes. Instead, we find ourselves entangled in the sticky sweet of trauma turned to story. We thought we might be led cleanly by the hand, instead we are bound to get it all over our clothes, to make ourselves a little sick. The tour ended suddenly. We’d had defectors. We’d put too much whiskey in the toddy. We were still puzzling over what we’d heard, and we still had to contend with an awkward mini-party at the end arranged beside a hearse, gathering everyone from every group, forced to acknowledge each others’ experiences over erodingly sugary cider and cookies. “We noticed small shoots of grass and weeds pop up where the candy house had been. We reentered the Woods having witnessed some magic at last.”

Rather than a cemetery’s object lesson on morality/mortality, H&G dwells not on what was lost but on the problem of the survivor. How do we integrate (or not) the dislocating experience, the eminently sayable but inarticulable? What strategies are at our disposal? “Bringing that adventure back into the old domicile . . . It’s staying that’s hard.” If we regard too closely the exceptional pain of others, the less exceptional circumstances show through, the slower violence happening before, happening after: famine, abandonment, murder, the unconditional demand for feminine endurance and resilience. “I would like to tell the tale so that it no longer makes me sad.”

Nabil Kashyap is author of the essay collection The Obvious Earth (Carville Annex Press). He is a librarian at Swarthmore College and lives in Philadelphia.

This post may contain affiliate links.