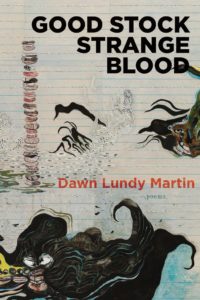

[Coffee House Press; 2017]

[Coffee House Press; 2017]

Dawn Lundy Martin’s poetry is eviscerated and eviscerating. In Good Stock Strange Blood, she languages violence and the varied textures and hues of systemic racism and intergenerational trauma while creating a new state of being, simultaneously cauterized and free.

I spent a long time reading and rereading Lundy’s newest collection of poems. It accompanied me through vicious hurricanes and record-breaking heat waves, firestorms and family crises, violence in Charlottesville and an overall rise in Hate Crimes in cities across the United States. It was a hard time to feel one’s way through. But I felt well accompanied by Good Stock Strange Blood with its unflinching witness to the fracturing and fractious present and the blood earth from which we come and to which we will return.

Imagine a beautiful

fracture, a wondrous

contortion, a

backbreaking arc. It will

do the body in. No way to

hold that kind of thing.

Oglala Lakota poet, writer, and artist Layli Long Soldier has said that for her poetry is a kind of prayer. I too think of writing as prayer, as a sacred act, one that enables us to remain unflinching in the face of centuries of violence and trauma while also arcing toward another, possible future.

In Good Stock Strange Blood, Lundy weaves these tendrils of damage and potentiality. The book opens with an interrogative prologue, an intimate dialogue between reader and writer, between author and the intimate relations of the written word.

“Why exhale after the inhale? The breathing is the mantra. Could trauma be keeping us alive?” the intimate asks.

“What happens is we walk through a door. On the other side of the door is a manifested future place. It’s configured very differently from this one. Its shape is different. But we created it so we recognize it; we understand its workings, which are mostly based on intuition. In the book, what is keeping us alive is the ability to imagine something very other than what’s been shoved down our throats, what’s been taken up in our cells. To imagine something other is to leave the known world. No death. But, instead, the door. To place a body alongside the grubby stranger, and then the stranger is a lockbox, and then voilá: a self is three intentional selves. And, the three selves are like different manifestations of the thing we call “blackness.” The writer responds.

And so the book begins. It is not an easy genesis. As Octavia Butler writes in Parable of the Talents, “In order to rise/From its own ashes/A phoenix/First/Must/Burn.” And burn she does; the I, the eye, of Good Stock Strange Blood, marks her own metamorphosis, from “The Traces of Catastrophe” to “The Book of Love”.

Seer said, betrayal is always

a symbol of the soul being

upgraded.

But the metamorphosis is distressed by the acid in our saliva, on our tongues, in the words themselves through which we try to make cogent something that is and should always be incomprehensible.

To imagine a future as foretold now.

To refute “it” am “s/he” —

—white space-only adornment—décor.

—peel back underneaths—

—hollowed be thy rage—thy cube—

Instead, slow cool into dead star,

then nothing—

And yet, it is in this incomprehensibility that the writer’s linguistic impulse resides. In the gathering up and reaching out to a stranger, to another, to us. Martin fearlessly thrusts her hands into the “hole the earth made” and draws up:

If I were looking from the outside—

I’d think that a thin ancient would not pulse so loudly, would

be automatically removed from the atmosphere, lose its atomic struc-

ture, its relatability. We were driven. Or we were rode hard. Mule-like

on feathers. This notion of sustainability: black vultures every-

where, neat white stars under wings, good at cleaning up road car-

casses. What a mess mess, your weak veins, your lifelong addictions.

What you then must witness is the vulture devouring the exposed red

and fly soaked— unrecognizable.

One of the many irreconcilable experiences that Martin confronts in Good Stock Strange Blood is that of the black body, one that, like land in the play of the book’s cast, “exists in a perpetual state of longing, enclosure and toil.” But the black body is not only a metaphoric one, Martin locates herself, a brother, mother and father within the text, within the brutal legacy of black experience and the ways in which intergenerational trauma can live and breathe in the intimate lives of families.

In the opening poem, “Aglow this bent,” Martin asks,

How to live between Mother and time?

As if born into the self watching

the self, already made, formless, then out of clay.

Feel the hump of drape. Here: the body, flesh

inevitable, unsatiated hunger like a whip—

Instrumental fissure, instrumental fish, whose rasp

a whip, a book, a story left in the dark body,

to reach fingers out toward shine of morning, eyes squinted,

and find there only cordgrass, some smoke or a warning.

And the warnings can be deafening for colonized peoples, oppressed peoples, for Native and Black people alike, to not speak, to not write about the extraordinary toll our survival has taken. To never name the levels of violence that we turn in on ourselves as if a scalpel to excise the cancer of subjugation. But Martin takes no heed; the pages of this book are rife with violence, both outside and within the family, the home.

My brother bends away from the hose that beats him. Basement is a

Watery place. I think of privacy and houses, what they allow for, their

Intimacy of enclosure. We never heard a word from over there and they

Never heard a word from us. How the home seals off the world, creates

a hole in the world, and there is no joy in that. To watch a teenage

boy compressed and the heart still beats, is hiss, is what hatred made.

God will not save you.

To be severed from and to sever. To be brutalized and to brutalize others. And within all of it is Nave, another character in the play of the book, who “is both haunted and empowered by connectedness to ancestors and traditions.” In Good Stock Strange Blood, it is this place that Martin is writing both from and towards. As she writes, “any existence inside of both loss and abundance feels impossible.” But it is the writer’s labor to try.

Scraps, bright against the sea,

migrant legs almost

drowned already, a narrative

In Evidence of Things Unseen, James Baldwin writes that “the history and situation of Black people in this country amounts to an indictment of America’s legal and moral history.” In times such as these, when so many are calling for a return to something more democratic, more in line with the “promise of America” — never mind that promise was born of the attempted genocide and continued erasure of Native peoples and the enslavement of and continued assault on Black bodies and lives — Good Stock Strange Blood is a scythe, a fractured and speculative poetics that renders the promise of America mute in the face of its own brutal origins and the generations of violent progeny that have emerged from its wake.

Aja Couchois Duncan is a Bay Area writer, capacity builder, and nature lover of Ojibwe, French and Scottish descent. Her most recent book, Restless Continent (Litmus Press) was selected by Entropy Magazine as one of the best poetry collections of 2016 and the California Book Award for Poetry in 2017. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from San Francisco State University and a variety of other degrees and credentials to certify her as human. Great Spirit knew it all along.

This post may contain affiliate links.