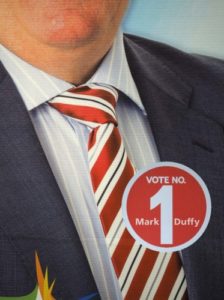

One of the central questions of politics is representation, whether direct or electoral, optical or structural. And perhaps the photograph can tell us something about this difficulty; for each picture, owing to the de facto plenitude of the visual field, marks a surfeit or excess of information, whatever the intended subject. This impurity of content is exploited to keenly satirical results in Mark Duffy’s Vote No. 1, an appealingly garish collection of photographs of Irish campaign posters from 2014 elections.

The coil-bound book lies flat so that its facing pages may remark upon and ironize each other, and each of the first 100 copies boasts a unique cover made from the original propaganda; beyond which the materiality of the corrugated plastic signs is foregrounded in the photographs themselves. The ridged plastic grain of the posters becomes an ambient refrain, alluding to a washboard tactility that impels closeness, even as closeness abstracts.

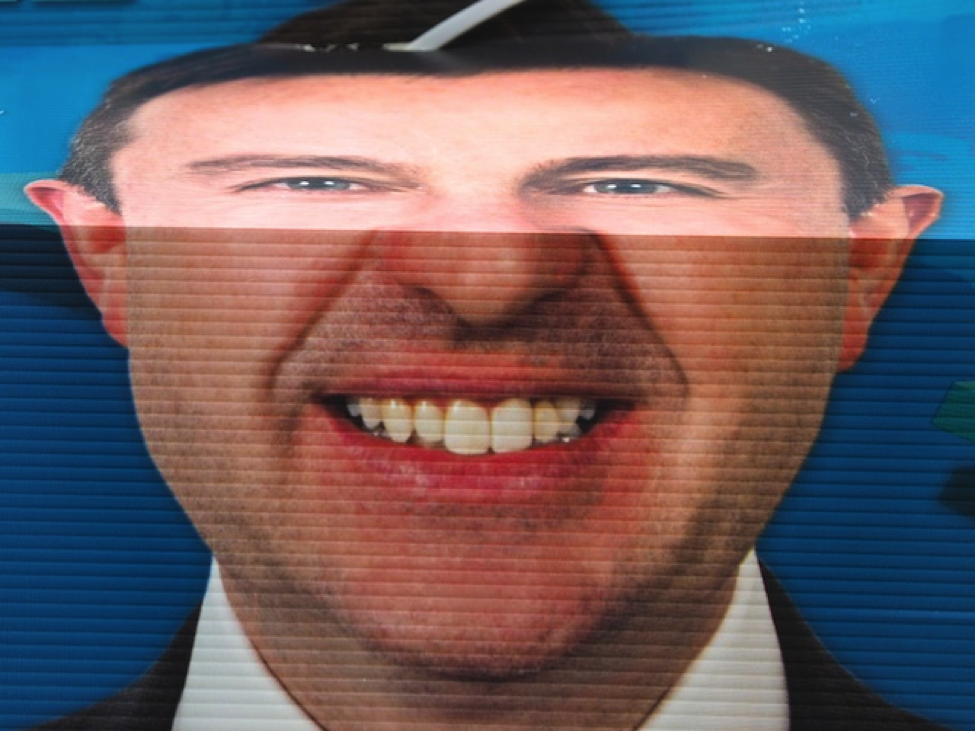

Through his excoriating practice of re-portraiture, Duffy treats the candidates portrayed in the posters anonymously. Faces are not so much framed as segmented: we see a smiling visage halved unto a cheshire grimace, or two separate likenesses asymmetrized by recombination, as in a children’s flipbook. With gruesome literality, the interchangeability of candidates is visually rendered as a kind of pan-partisan chimaera, further divisible at market, no doubt. Duffy’s camera is incredulous of the integrity of each subject. This is not only put across formally, as so many extreme closeups and recontextualizing frames, but with a careful eye for the contingent detail that accrues to each poster as a duplicate of duplicates, singularizing and debasing it at once. These signs appear differently tattered, faded by the elements, or vandalized, marked by the crude opprobrium of whatever hand, spontaneously juxtaposed of a given moment with all the incidental information vying for attention in the street. The campaigning politician’s attempt at ubiquity must tarry with the uncanny, a term describing subjective unease before such duplication in the field of vision.

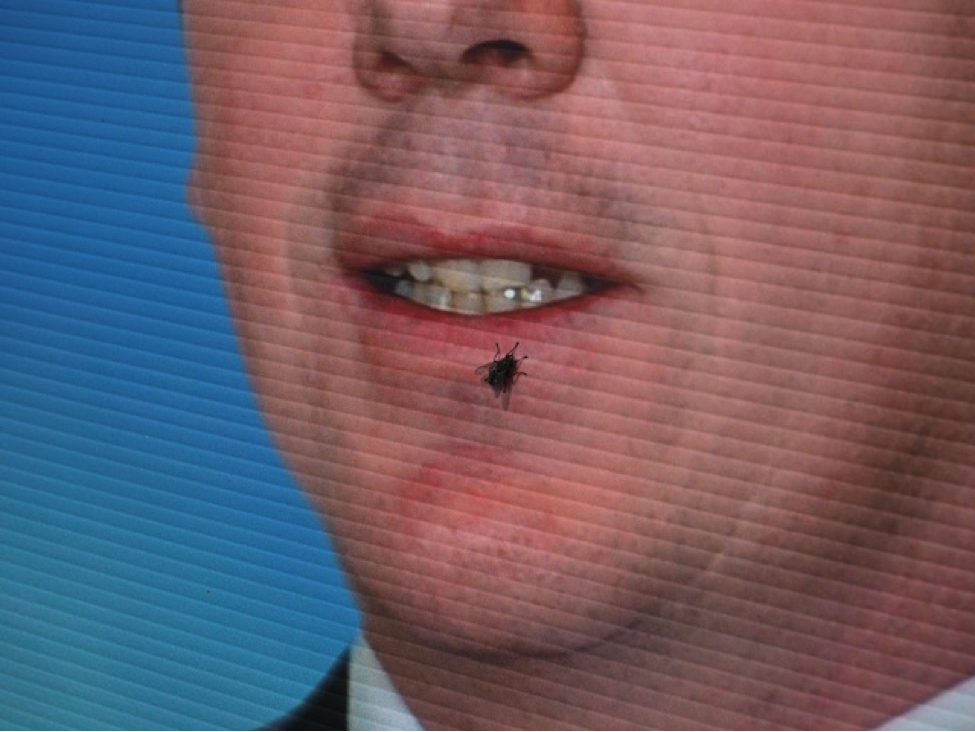

Much as the likeness of glazed cheeseburger, enlarged to unappetizing dimensions, beckons distastefully from deli windows citywide, Duffy’s subjects are larger than life and irksome; and an ill-proportioned depiction in the wrong light will only spoil the appetite. So the Brobdingnagian scale of these faces heightens upset: one looks upon enlarged pores like a swarm of insects; bared teeth like fenceposts; pixels like a smeared paste on the face; tectonic wrinkles; and one shudders at the base sublimity. Of course one ought to impugn white supremacy and its appearances, and these close-ups refute the consistency of any conservatively photogenic flesh. To this end, some of the most cathartic pages are those so near to the subject as to be pictorially dissolute: halftone clouds belying the consistency of any visage.

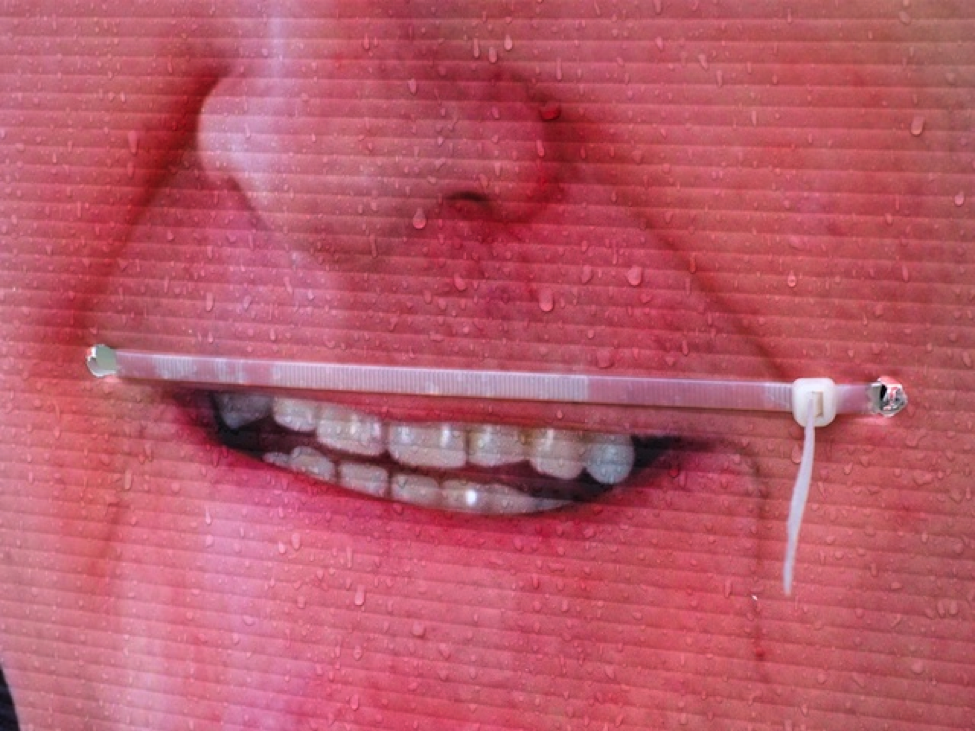

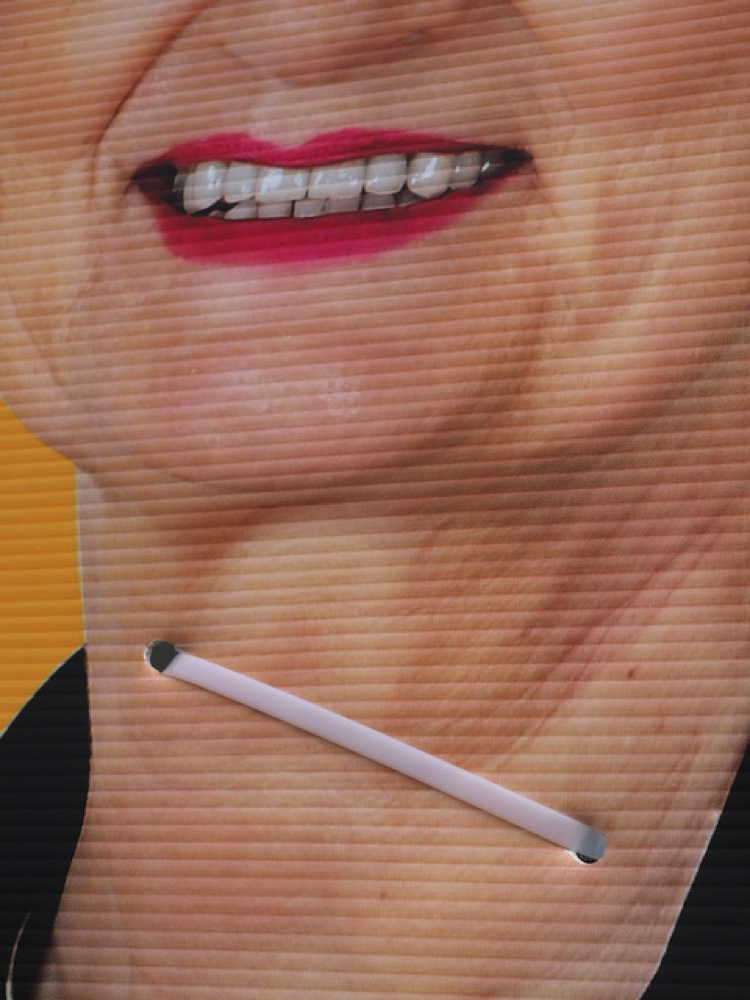

The book opens on a pointillistic close-up of blue sky, across which a halved face smiles fiendishly, throat punctured by a plastic band fixing the sign to a post. Duffy’s decision to treat each campaign poster as a mixed-media composition, foregrounding the incidental disfigurements as part of the message, is gruesomely rendered here, and on the pages immediately to follow. Next to a second abstract sky, clouds sullied by impertinent dirt, a thin-lipped grin appears above a bolt placed squarely in the jugular. Two-panel panoramas leer from the following pages, inconsistent diptychs of distressing proportion, even in a book. A fly preens upon a blurred lip; a coloured poster peels symmetrically below the eyes of a plaintive campaigner, its surface otherwise decorated with wart-like rivulets of water, giving the impression of face-melting tears. Elsewhere, collecting on the brow, raindrops give the impression of a nervous sweat. We are treated to trepannings; a painted mouth appearing to drool grey mud from its corners; two separate half-smiles align at the margin, sharklike. One is all gums and the other sharpened teeth, but neither is the more sincere, appearing in such extreme close-up as to resemble aerial reconnaissance of some unspecified terrain.

The photographs tend to greater abstraction over the course of the book, some emphasizing textures rather than figures, leaving alone disfigurements. Mechanical interference is photographed, and these results are placed combinatorially, so as to resemble the climactic revelation of machine beneath the waxen flesh of a Terminator robot. These fixtures balance the desperation of each isolated gaze, a blue-eyed vacancy without address. Those pages devoted to geometric interference, the folding of posters as though their subjects were contorting themselves, are didactic and sculpturally apt. Decals on the sides of cars mar the face suggestively: where the lip of a window coincides with a candidate’s mouth, one expects the jaw to open and close like a ventriloquist’s dummy. No doubt it is the same in person.

It is this trenchantly cynical optic, which greets campaign signboards as litter in advance of any election, that alludes to a more transparent civics. But how does one photograph such a future? Duffy’s obsessive close-ups of those portions of the signs depicting sky, a supportive motif and opaque proxy for a truly universal element, are a savvy gesture in this direction. Vote No. 1 condenses the political-processual incredulity of a moment into a cathartically funny package, one that implores us to look more closely at the ideological detritus crowding our boulevards, streets, and imaginations.

Cam Scott is a poet, essayist, and improvising non-musician from Winnipeg, Canada, Treaty One territory. He performs under the name Cold-catcher and writes in and out of Brooklyn.

This post may contain affiliate links.