That the visual is inseparable from the textual is a central principle of M Kitchell’s work. His curation of the press Solar Luxuriance and his own work constantly push the act of reading as no less of a ritual than that of writing. This interview concerns the role of these pursuits in his new book, a hypnagogic cycle of five stories, Hour of the Wolf, published by Inside the Castle in December of 2016.

That the visual is inseparable from the textual is a central principle of M Kitchell’s work. His curation of the press Solar Luxuriance and his own work constantly push the act of reading as no less of a ritual than that of writing. This interview concerns the role of these pursuits in his new book, a hypnagogic cycle of five stories, Hour of the Wolf, published by Inside the Castle in December of 2016.

Could you introduce yourself as a poet, which is the way I see you with respect to Hour of the Wolf?

I consider myself a poet inasmuch as I exercise a sort of post-Bataillean indulgence of la haine de la poesie — and in the idea that “poetic effusion” is exercised as a sovereign behavior.

Let’s start with a question about the time you spent writing Hour of the Wolf. How long did it take for you to finish this? And do you consider this work a finished book?

The initial text was written in the span of 72 hours — a burst of energy, a sort of restrained violence that pushed the text forward. The book is open, in a sense, in that the narrative refuses finitude — in that way the book is unfinished.

Where did you write this?

In my bedroom in San Francisco, CA, which is more or less the bedroom in the First Cycle of the narrative. The space described as the sort of ‘mirror’ apartment is the actual apartment beneath mine, which was empty at the time I was writing. I had, in the days before the writing of the text, spent some time in the empty space.

Why did you decide to title this piece Hour of the Wolf?

I stole the title from Ingmar Bergman’s film of the same name. It is a film which I think is imperfect but still holds a heaviness that I find necessary. I’m not sure if referring to the ‘witching hour,’ or the hour between 3 and 4 am, as the ‘hour of the wolf’ was Bergman’s invention or something rooted historically, but since seeing the film years and years ago I’ve always thought of that hour as such.

When I open this book, I feel that it is more like unreal cryptology, which looks like divided blocks of text and words (and some bridges and scattered marks) than a normal text. I had a hard time understanding while seeing. Did you calculate your text to have this effect?

I think that having a hard time understanding, because the text doesn’t resemble a normal text, is an experience of disorientation. To experience disorientation from a text is a level of affect that can expand the space of the text itself. In that sense the effect is calculated, but the effect is dependent upon the reader’s response. Similarly, reading involves looking, so I want the text to be thought of as something to look at in addition to something to be read — especially if the visual elements extend or expand the reading experience.

For the moment, let’s focus on Hour of the Wolf. Why did you divide the book into five cycles?

Hour of the Wolf is divided out of a sense of formality: I had an interest in the text funneling to a somewhat neutral silence, or perhaps a void — the first section is the densest, and in terms of pure word count, each section becomes more engulfed by the violence of the blank page (an overwhelming). The forms break down and become more fragmentary as the book moves along.

On the first page you note that Hour of the Wolf was written after James Lee Byars. Who is James Lee Byars?

James Lee Byars was an American artist who died in Cairo in 1997. His work is very important to me on many levels. In the First Cycle, the initials/coding (QR, OQ & QD) found on the stele are taken directly from Byars. As linguistic signifiers, these were used by Byars throughout his body of work — a single example: The White Mass, installed in the Church of St Peter in Cologne. Hour of the Wolf was written during a period of intense research into Byars’ work; as such I feel like his aura haunts the text. The notation is both an acknowledgment that his work led to this text, and an invitation for readers to consider connections.

Image source: Byars, James Lee., Friedhelm Mennekes, Heinrich Heil, and Wolf Günter. Thiel. James Lee Byars: the white mass. Köln: König, 2004.

While you indicate that the text is written after James Lee Byars, this work delivers the tone of an autobiography of a poet who might be yourself. The autobiography as fantasy or fictive narrative is no longer something very surprising for readers nowadays. However, I can’t simply define your autobiographical writing as fantasy. I think in your writing there is something that pushes itself beyond autobiography toward a silence through poetic words. What do you think about the relation of this autobiographical or posthumous silence of yourself in your work?

I’m always interested in experience — whether it be something akin to Bataille’s “inner experience,” the experience of the reader interacting with the text, or my own experience in the writing of the text. Narrative fragments throughout my work almost always take the first person pronoun (there are exceptions, notably in Hour of the Wolf where I wanted a different pronominal positioning in each cycle of the text). I position myself into the “I” and the writing becomes my own exploration of the narrative space. In that sense the text becomes fictitious autobiography, or perhaps hyperstitional autobiography.

As you’ve expressed elsewhere, is this relevant to Bernard Noël’s reading of Bataille’s concept of the unexpressed-expression of the impossible? How do you make the said the unsaid in your writing? You express something. But it goes back to silence, and paradoxically by returning it to silence (the unsaid), it becomes a different kind of expression of the inexpressible, which is a very profound silence.

I think you successfully articulated my oft-used attack: expressing something but then undermining that expression by returning to silence.

Also, your writing reminds me of this quotation from Bataille, found in Bernard Noël’s essay “The Question”:

“I do not distinguish between freedom and sexual freedom because depraved sexuality is the only kind produced independently of conscious ideological determinations, the only one that results from a free play of bodies and images, impossible to justify rationally…. Because rational thought can conceive of neither disorder nor freedom, and only symbolic thought can, it is necessary to pass from a general concept that intellectual mechanisms empty of meaning to a single, irrational symbol.”

Of course, you are not writing depraved sexuality in Hour of the Wolf. However, my impression is that there is a desperate desire for freedom which seems to elliptically touch on a very unusual kind of erotic freedom throughout the book. What do you think of eroticism in this book?

My interest in eroticism is tied to an interest in freedom, in the sense that — to once again return to Bataille — an erotic effusion can be considered a sovereign behavior. It is similarly often a “limit”, and I’m interested in limits.

The eroticism in Hour of the Wolf is present, but not the cornerstone. The only direct touch, perhaps, is in the fourth section, when eroticism enters the narrative directly instead of in the abstract.

In general, eroticism offers a way to construct the fantastic within narrative, to offer an impossibility that one could presume — could such a construction convene into reality — would offer a level of experience unmatched by those experiences that the Real inherently has to offer. Eroticism as a mysticism, perhaps.

Your text starts with black backgrounds:

Here you are presenting a repetition of short chants followed by an ellipsis. Ignoring the abstract content of these chants, the repetition of short sentences seems to hold an importance in your work. Could you say why you began the book in this way?

I am always interested in the form of the book — the work being a book in its construction, a bringing together of parts that add up to a whole. I like to begin my books with a sort of invocation. To start the narrative in a state of terror & absence, a state of telling, a presentation of some sort of abjection thrusts the reader into an emotional state (ideally) without the necessities of a full narrative to get her there. In a way, it’s a shock-tactic to prepare the narrative space.

In your text, especially in the First Cycle, the image of darkness, silence, and blurriness prevails. Also, the text itself often leads the reader to a state of sleeplessness, exhaustion, and inertia. Atmosphere in the text is a stillness in the enclosed space or architecture. This image or consciousness becomes stronger when the text moves into, in your words, “the hour of wolf.” During this time the body is described as weaker, even paralyzed. It seems to me that the hour of the wolf is not really time in an ordinary sense. It feels like some kind of unknown region that makes you or the narrator feel an intensity related to the idea of the phrase “you do not understand.” Why is the phrase “you do not understand” important? If you do not understand, what brings you to write any word in the text? How is the movement of thinking or writing possible?

There’s an inherent contradiction in my interest in writing what falls away from the potentialities of language. It seems like at a certain point the only way to justify the concept with language itself is to insist upon any impossibility of understanding.

Do you consider Hour of the Wolf as a long poem rather than a novel? You once mentioned to me that Bernard Noël’s poetics greatly influenced you. It seems to me that your work emits a poetic force of words and images, if not, more fundamentally, marks and scars of silence.

At this point it does not matter to me whether something is a poem or a novel. I’m more interested in writing in itself — the collusion of genres toward a heterogeneous text. This draws from a sort of post-Bataillean poetics explicated by many French writers of the 60s and 70s, such as Anne-Marie Albiach, Claude Royet-Journoud, Bernard Noël himself, Danielle Collobert, etc. While they are often referred to as “poets” today, they insisted that they were not writing poems but rather that they were writing writing — l’écriture. This is tied of course to developments in structuralism and post-structuralism, Barthes & Derrida perhaps the most, but also in Blanchot (though he assumes the term literature instead of writing, perhaps). A formless writing that carries affectivity is what I’m interested in. I think it is often questioned due to my insistence on narrative elements, and it seems like when narrative is involved a description such as “a poetic novel” is used instead of “a narrative poem.” I suppose it’s not that important though, as the writing can be tied to genre without losing its unknowable (in the Blanchotian sense) “core”.

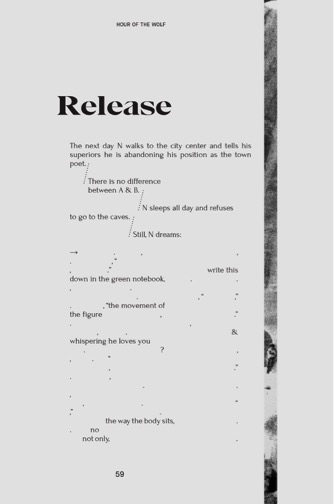

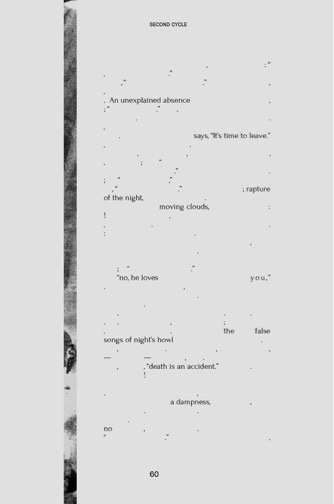

Now I would like to enter the Second Cycle. You divided it into 1. Sand 2. Melt 3. Emptied 4. Release 5. Excess (Or Escape). For me, 4. Release looks very different, thanks to its sparseness and lots of omissions, in addition to confusing punctuation marks. Below I include two respective pages.

My question is, using these scattered marks — words and signs — to push toward the limit of remembering and forgetting some form of dialog, are you trying to indicate that the text is escaping itself? Or the opposite? Inside the text, or inside the poem, do you think an escape or exit is possible? Many poets desperately desire to “leave.” Even though there is a desire of leaving, poetry seems to turn around in its own circles of escaping and remains to still escape further inside its own marks. Your escapism toward a utopia seems to have, always, the other side of a claustrophobic irreality of death-space (or writing-space). In the Fourth Cycle you write: “an escape from the excess of reality. A calm outside of ennui. Satisfaction met in every capacity. The man is a saint and his presence is in remembrance of your sins. You walk around the palace to find all the false doors. One of them turns out to not be false. Inside, you shut the door behind you. You close your eyes and lay down to die.” What does poetry reserve with its excess of writing in its own special refusal of the world if there is nothing to await other than a laying down to die? What is a utopia that gives you warmth and calmness, and what are apocalyptical vision and space in poetry? Are they in opposition?

The scattered marks are another attempt at expressing the inexpressible, with the textual fragments appearing as gasps for breath, linguistic limits that are all that can be encountered. A demonstration that at this point in the narrative we’ve reached something beyond limits, something impossible. This is what the work is after, this impossible. And in a sense, this is an escape, the “outside.” Something apart from the present, the past, or the future. If death can be considered this “outside,” this “impossible,” then I would say it’s not quite an “escape” but something other.

I think this outside cannot be considered in opposition; between something positive (a utopia that gives warmth and calmness) and something negative (apocalyptic vision and space). Rather, it must be something beyond this binary. That’s where the escape lies. But, perhaps what would be a warm escape would be a sense of floating (which is another image/concept that appears repeatedly throughout my work), a sense of honest freedom, from the body, from the earth.

In the Second Cycle, the bridge that you use leads the text to an imaginary of subliminal consciousness: caverns, caves, pits, etc., beneath or at the core of the earth. The text seems to go into a depth or the imaginary of depth in (un)seen intimacy to the sacred inside the text. But, in the Third Cycle, you also write that the black hole (or cube) where you are stuck to die is a depthless empty region. The reason why I bring this up is that I would like to ask: what is your understanding of depth and surface in writing? Could you tell me the relation between the surface of signifiers, the sacred and silence in your text? How they play out with each other at least in your work?

The sacred, the silence, the impossible. In Bataille’s conception, the sacred is created through sacrifice — and this can either be religious in a traditional sense, such as in Christianity the story of the sacrifice of God’s son for the world, or religious in a way apart from theism, such as the sacrifice of the self to experience. I believe that there is much more to text than the surface, yes, and this again goes back to Blanchot’s discussion of a part of literature that is impossible to know. Something unspeakable, something unsaid, something perhaps a bit like Benjamin’s idea of the aura, but taken away from a material object and displaced into the text itself. The death of a character is also a textual event to indicate the sacrifice necessary for the sacred. The sacrifice of expression or even text itself (such as the formal play of punctuation noted above from the second cycle) is another attempt at the creation of the sacred, but in that case it is more so on a level of affect, a zero-degree for the reader (another example would be in Bataille’s Madame Edwarda when the writing gives way to streams of ellipses).

As for the Third Cycle, I have a short and simple question. Why are plants like succulents important for you?

Succulents — specifically cacti & cacti-like euphorbias — are important to me because they are so alien, so strange and often violent, yet they are alive, they grow, they can die. They fascinate as objects, and I write about them to carry that fascination into the text. I believe in an occult region of these plants because of the mystical states I associate with them. Maybe just as objects of meditation. They are ghosts in the sense that they are simultaneously alive and dead, perhaps.

The Final Cycle seems to visualize your thoughts from earlier Cycles with pages filled more with absence than writing. What is the “non-action of language” for you? Perhaps this is found in the repetition of the word “white” in connection to “the page,” “sea,” “the night,” and “light.” Do you relate this to the conceptions of the neutral and night in Maurice Blanchot and Roger Laporte (which you discuss as part of your “Haunted House Series” in Entropy Magazine, March 27, 2014 and April 3, 2014)?

Language is used to signify meaning. Its common use is to represent instead of to perform. Language as futility. This is the non-action of language.

White: first, the blank page. The black of ink, words printed on white, is inherently a violation — there’s a performed violence. The sea, the night, light itself, these are visualized as flat planes — like the page itself — and in this sense can be violated (or interrupted) by the word in the same way. The blankness, the unknowing. Blanchot’s Death Sentence does this. Doubly so with the removal of the post-script in its second version, those few paragraphs where Blanchot speaks directly to the reader.

Do you feel the recurring desire to abandon being a poet as N does in Second Cycle? If so, why and how?

The Second Cycle addresses my thoughts on the total inutility of such a position. I think there’s a hint toward the issue of community in the idea, and my interest perhaps goes back to that of Bataille, Blanchot, Duras, etc., spoken of in Blanchot’s The Unavowable Community. A community of outsiders. I think that outsideness, while perhaps not a necessary state for all poets, is an essential part of the poets and writers I find most important.

Do you think being a queer poet makes it more difficult to write a poem because its desire is constantly pushing against banality and the categorization of genders and sexualities? Is this why you move yourself toward a site of death? But death as a fact is also banal. Maurice Blanchot (and Roland Barthes) distinguished dying from death for this reason, because dying is infinitely unknowable like writing, unlike death as a fact. What do you think about this?

I suppose this is a fault of mine, to not necessarily disconnect death from dying. The interest is in the unknowable act of dying, but representation constructs that absence in the past tense. I’m working further toward an approach of dying instead of death, I think.

For me if desire were not so impossibly complicated I would not be interested in writing about it. Perhaps pushing desire toward death is a way to banalize, to some extent, what is so incredibly complicated.

Hyemin Kim lives in New York and studies queer experimental poetics and cinema in the Feirstein Graduate School of Cinema

This post may contain affiliate links.