[Europa; 2016]

[Europa; 2016]

Tr. by Ann Goldstein

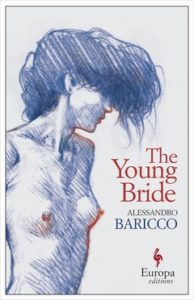

Known in the United States for his incandescent novel, Silk, and the same-titled, 2007 movie, Italian writer and director Alessandro Baricco’s latest novel to reach our shores is The Young Bride, translated by the inestimable Ann Goldstein. This novel is a captivating, fable-like story about a family that lives each day the same as the last in order to suspend the passage of time. It is a quirky, beautiful, and warmly humorous reflection on how the fear of our own mortality affects the way that we live our lives: with The Young Bride, Baricco risks surpassing his prior renown.

Baricco has created an imaginative, self-contained world for his characters, a family of five: Father, Mother, Daughter, Son, and Uncle (each identified as such, never by name), who live in a country manor house somewhere in Continental Europe in the early 1900s. The family’s indolent lifestyle is sustained by means of an inherited textile business and the services of Modesto, the aptly-named servant who has been with them for fifty-nine years. Modesto never invents or improvises as he ushers the family through its perfectly sequenced and unvaried days. In this constancy the family tries to forget that time is passing and death, inevitable: “In the repetition of actions we stop the world: it’s like holding a child by the hand, so that he doesn’t get lost.” This cosseted monotony is interrupted by the unexpected arrival of the Son’s betrothed — the young Bride — now eighteen and, as agreed three years prior, of appropriate age to marry the Son, an arrangement that the family had largely forgotten. To the young Bride’s surprise the Son is abroad on family business, and his date of return is uncertain. This leaves her little choice but to stay with the family and await the Son’s return.

It does not take long for the young Bride to recognize the family’s peculiar insularity. Interest in outside affairs risks exposure to unanticipated, uncontrollable situations; thus, the family focuses inward, collectively creating a pleasurable lifestyle in which one day seamlessly flows into the next. For instance each morning, without fail, starts with a three hour breakfast featuring a “torrential flow” of delicacies:

white and dark toast, curls of butter on a silver plate, honey, chestnut spread, and a jam made with nine fruits, eight varieties of pastry culminating in an inimitable croissant, four different flavors of cake, a bowl of whipped cream, fruit in season always cut with mathematical precision, a display of rare exotic fruits, newly laid eggs cooked three different ways, fresh cheeses plus an English Stilton, thin slices of prosciutto from the farm, cubes of mortadella, beef broth, fruit braised in red wine, cornmeal cookies, anise digestive tablets, marzipan cherries, hazelnut ice cream, a pitcher of hot chocolate, Swiss pralines, licorice, peanuts, milk, coffee.

Gluttony is not the family’s only indulgence. Both the Mother and the Daughter take great interest in instructing the young Bride on the intricacies of giving and receiving sexual pleasure, and Baricco details this education in sensitive prose that conveys the women’s absence of pretense and disarming honesty about their bodies and desires. The family balances these hedonistic impulses with a scrupulously maintained emotional restraint: excitement is discouraged; unhappiness prohibited; and a decision, once made, is “never changed, for obvious reasons of economy of emotions.”

But the family’s efforts to maintain an existence impervious to emotion, unpleasantness, and death is burdened by the weight of a family legacy: “For a hundred and thirteen years, it should be said, all of us have died at night, in our family. That explains everything.” The legacy makes death as imminent in their minds as the darkness that follows each day. Indeed, the three hour breakfasts serve as rites of thanksgiving for having survived the previous night. The Father vows to break this family legacy: “I won’t die at night, I will die in the light of the sun.” He commits that when the time comes, he will look death in the eye and accept it with grace and dignity rather than tremble in the dark and wait for it to devour him.

This legacy is not the only darkness that belies the family’s façade of unmarred happiness. The Uncle suffers from a “mysterious syndrome” that keeps him in an almost perpetual, somnolent state during which he remains fully cognizant, able to hear conversations and even undertake certain activities:

He could shave in his sleep, and on occasion he had been seen to play the piano as he slept, although he took slightly slowed-down tempos. There were even those who claimed to have seen him play tennis in a deep sleep: it seems that he woke only at the change of sides.

The young Bride learns later that the Uncle’s syndrome is an involuntary response to his secret and repressed sorrow of losing the only woman that he ever loved.

The Young Bride is character-driven, and the novel’s cast deserves our fascination. As demonstrated previously with Silk, Baricco is masterful at inventing quiet, contemplative characters, and there is so very much to admire here in his rich depiction of their vulnerabilities, spiritual generosity, and innocence. The writing pulses and flares with revelation of the frailties that draw them to one another. Baricco deploys some cleaver meta-fictional elements throughout the novel that create mystery surrounding the identity of the narrator, and overall these are handled deftly, folding into the novel’s narrative rhythm rather than distracting from it. And the prose is so pleasurably precise that it is impossible to think that Goldstein’s translation has failed to capture any of the emotional nuance and supple expression present in the original.

With The Young Bride Baricco has created an original and exquisitely crafted exploration of how we anticipate death and the ways that our conception of our own mortality can affect the capacity to live and love — a heavy topic, for sure, but one that the author handles with humor, delicacy and warmth. We are reminded that accepting death requires great courage and that we must find the courage, otherwise the act of living surely is diminished.

Lori Feathers is a freelance book critic. Her recent reviews can be found at Words Without Borders,World Literature Today, Three Percent, Rain Taxi and on Twitter @LoriFeathers

This post may contain affiliate links.