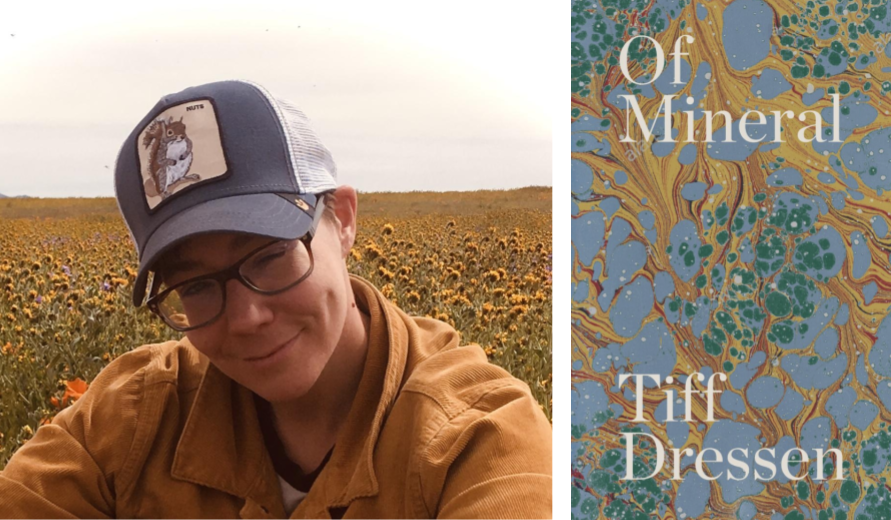

I first met Tiff Dressen through the Bay Area Correspondence School (BACS), an epistolary arts community. Over the years, I came to know Tiff as a generous collaborator who is willing and eager to experiment with form and content. Whenever a BACS member would suggest a fun creative activity, Tiff was game to try it. They seemed equally content to blend into the crowd or to shine on stage. This thoughtful way of moving through the world, of balancing active participation with respectful distance, is elegantly displayed in their new book of poems, Of Mineral (Nightboat Books, 2022).

In this collection, the self-described flâneur takes the reader on a literary journey through the streets of the Bay Area, the paths of history, and the neural networks of their own mind. Like the poet themself, Of Mineral has many layers to discover. Over the course of our email conversation, I was honored to learn so much more about a person I’ve respected for years. I hope this interview will introduce Tiff’s work to new audiences while also providing the fans of their previous poetry collections with a refreshing new appreciation of this deeply complex author.

Della Watson: So Tiff, tell me, what’s a mineral?

Tiff Dressen: For me in my creative endeavors, I often use mineral and element interchangeably even though they are different. Elements being fundamental units, they can’t be broken down further, at least, not easily, not chemically.

Elements like oxygen, silicon, iron, and calcium combine to create the bulk of the earth’s crust in the form of minerals like feldspars, quartzes, micas, and calcite, which are inorganic solids with a specific chemical formula. Then rock is formed from combinations of minerals through forces like extreme pressure, heat, lava, or accumulation of layers and layers of organic and mineral particles over unfathomable periods of time. That said, what captivates me in this moment is the “over unfathomable periods of time part.” I just can’t grasp geologic time. In the last poem of the book, I quote a stanza from George Oppen’s “Of Being Numerous”:

We might half-hope to find the animals

In the sheds of a nation

Kneeling at midnight,

However, what comes after that stanza is also very critical to my own thinking, creating and dreaming:

Farm animals,

Draft animals, beasts for slaughter

Because it would mean they have forgiven us,

Or which is the same thing,

That we do not altogether matter.

The line: “That we do not altogether matter” is a deep, interior mantra for me. And coming into daily contact with the mineral/rock world reminds me of that. That we’re flickers of consciousness passing through (and doing about as much damage as we can in our transiting). But the mineral/rock world also reminds me that I’m part of earth, I’m of earth, that’s a kind of identity, and I can find solace in that. And, in a sense, communing with the mineral/rock world is also another way for me to contemplate time, and to understand that the destructive/creative geologic processes are always underfoot. It’s hard *not* to feel that when one lives and works so close to the Hayward Fault!

Your cat, Briquette, is mentioned in the book. How do pets function within your poetic ecosystem?

There’s really nothing more I enjoy than talking about my cats! Yes, I am that type of person.

I actually have two long-haired black cats, Briquette and Godzilla, also known as “little g” because she’s kind of small and squeaky, in comparison to her big sister. They are not littermates but there is definitely a big sister/pesky little sister relationship between them.

My partner, Kate, often says that there is a human trapped inside of Briquette, and I feel that’s pretty accurate. I have had moments when falling asleep or awakening, sensing their presence in the room with me and distinctly feeling as though we were of one consciousness. It’s an extraordinarily peaceful feeling. I spent so much time during the pandemic working from home, and thus more time in their presence, observing them, listening to them, being their devoted servant, feeling the way they move energy around the house, I see myself attempting to understand the world through them. They are breathing, stalking, vivaciously alert poems. And they bring me joy every single day.

That sometimes surreal experience of quarantining at home during the pandemic provided many of us with changes in perspective. At the moment, I’m thinking of two poems in your book (“Poem for March 2020” and “Holy Week: April 2020”) that specifically reference 2020. I see a sort of pandemic timeline in your book, or perhaps rather a record of that/this unique period of history. Can you speak to how the pandemic impacted your work?

The poems in this book span a long period of time, for example, the first poem of the book “Theirs” is ~20 years old, though it was slightly revised while the manuscript was being shaped. Given that, there is a chunk of work in Of Mineral that was either written and/or rigorously revised during the pandemic. Those poems feel intensely domestic because that’s where life was happening for me‚—that and on my long meandering walks in San Francisco.

Even as maddening and all consuming as my job was during the early months of the pandemic, I spent more time writing. I had a fairly regular practice of journaling in the mornings—seeds of poems often emerged from those daily writings, which gives them a kind of diaristic quality. I was compelled to document what was going on, in the home, in the neighborhood, in the country, and around the world as best as I could, and as best as I could understand what was happening, what we knew of the virus, how we believed the disease to spread, how best to protect ourselves. Also, paying attention to who (which communities) were (and still are) bearing the brunt of COVID. This was also a period of time when I became more acutely aware of my privilege as a white person with a stable job, and the privilege of being able to work from home.

When/how did you know that this book was finished?

The poem “Poem for Epiphany #2” is the freshest poem in the collection and wasn’t in the original, submitted manuscript. The poem is my attempt to come to grips with the sudden, tragic death of a family member during the pandemic, trying to honor his memory, trying to write love into a tragedy. Once that poem was in the final manuscript, the book felt complete to me.

I notice that many poems have dedications or references to other writers. How do you see these relationships functioning? Are other writers and historical figures muses for you?

Indeed! I didn’t think much of it until the manuscript came together, then I realized how much my writing practice relies on other poets, past and present. For those poets who have left us, I sense my own desire in wishing to have known them or, at least, met them. But then I wonder if it’s the distance across time/space that compels me, through poems, to create a psychic bridge to them. Whitman’s tender poem, “A Noiseless, Patient Spider,” and the line: “Till the gossamer thread you fling catch somewhere, O my soul” has often served as a spirit compass. Continuing with that Whitman metaphor, I feel as though I am casting out (albeit slowly) threads upon threads and hoping they stick somewhere.

Other guides not mentioned in this book but who have appeared elsewhere in poems (veiled or unveiled) are Antonin Artaud, Paul Celan, Ebbe Borregaard, Eléna Rivera and then there’s this whole other thing—my experience (and filtering) of current scientific thinking and my reading of the Pre-Socratic philosophers like Thales, Pythagoras, and Parmenides, and Ancient Greek lyric poets including such Sappho, Moiro, and Alkman. Diane J. Rayor’s collection entitled Sappho’s Lyre: Archaic Lyric and Women Poets of Ancient Greece has been a rich source of inspiration.

This book does a lot of things really well. One thing I appreciate especially is how deftly and gently you navigate between different ways of organizing and understanding the world. The threads of disparate belief structures are interwoven in a way that feels very natural, yet outside of the poetic landscape you’ve created, some of those structures might seem at odds. As a reader, I don’t feel bombarded by any one worldview in particular. Instead, I see more of a mapping of how these things all intersect with each other in the real world. Can you speak to some of these influences and how they manifest in your writing?

Thank you for this question. And isn’t that just so much like life? Can there ever really be one predominant way of organizing and understanding the world? Okay, I’ll take that back. Should there be any one dominating way of organizing and understanding the world? And I say this as someone of primarily Northern European descent and raised in America who wants to acknowledge and respect the world views and narratives of people from other cultures and backgrounds and experiences.

Given that, I think what I’m writing is my life, which is composed of these various, and sometimes, conflicting threads. I want the poem to be flexible enough to carry what I’m experiencing on the street, the latest headlines, what science can tell us about our planet’s future by studying its past. How my own upbringing in Catholicism lingers in my consciousness. I have been working with scientists and engineers for most of my adult life; it’s the milieu in which I’ve spent the most time. For example, the headline (and article) I’m reading now: “The amount of Greenland ice that melted last weekend could cover West Virginia in a foot of water.” All these threads may come together (or not). Perhaps that’s what creates the balance you mention above.

The book also seems to ponder questions of invasiveness versus belonging. The reader is asked to wonder who or what is natural and accepted, and the answers don’t always seem easy. What are some of the specific types of belonging you want this book to address? What conversations would you like to provoke?

I think I owe my preoccupation with the invasive versus belonging theme to my partner, Kate, who spends a lot of her time both professionally and personally thinking about how to create Bay Area landscapes that incorporate more and more California native plants. Our hikes in nature unusually involve her identification (Latin and common names) of native wildflowers. And, naturally, discussions around what we mean when we say a species is native or endemic or invasive. We generally think of invasive species as ones who’ve been introduced into an environment via human activity and where that species takes over, squeezes out native or endemic species by using resources natives would otherwise have utilized.

In this book, I’m also thinking about this in the human context of manifest destiny, the “American Dream,” taking what you want because you think you’ve “earned” it or are “entitled” to it. Also, especially in these poems, thinking about invasiveness in a more personal way. For example, where I choose to go, how I take up space and resources especially in communities where people are struggling and have been struggling. Can I learn to pass through as lightly as possible without having expectations or making demands of my fellow humans? I’ve grappled with the question of belonging (and not belonging) my whole life and, I think, that’s also the fact of being a gender non-conforming queer raised in an uber heteronormative culture.

I think what I’ve learned through writing these poems is that belonging is an active process that begins with a respectful exploration (knowing and respecting boundaries), openness, and curiosity about where you are and who is there with you.

Della Watson is an avid collector of collaborations. She is the co-founder the Bay Area Correspondence School (BACS), an epistolary arts network, and the co-author of Everything Reused in the Sea: The Crow and Benjamin Letters (Mission Cleaners Books). Her work has also been featured in the chapbook the longer you stay here (Aggregate Space/Featherboard), the anthology Remembering the Days that Breathed Pink (Quaci Press), and in numerous journals, performances, and galleries. She currently lives in California.

This post may contain affiliate links.